Please Note: Our Box Office is currently closed for renovation. We recommend purchasing tickets online in advance to expedite your entry into the Aquarium. Tickets can also be purchased at the Information Desk in our main lobby today.

Three Decades in the Dry Tortugas

What we’ve learned after three decades of research on nurse sharks in the Dry Tortugas

By Nick Whitney, PhD on Monday, October 17, 2022

In this post, Dr. Nick Whitney shares a brief history of research conducted on a nurse shark breeding ground in the Dry Tortugas and what the science team has learned over the last 30 years.

This research, published in scientific journal PLOS ONE, was led by Adjunct Scientist Wes Pratt with co-authors that include Associate Scientist Dr. Ryan Knotek and Senior Scientist Dr. Nick Whitney of the Fisheries Science and Emerging Technologies program in our Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life.

A Brief History of the Study

What does Wes Pratt, New England Aquarium Adjunct Scientist and shark expert, have in common with “Thumb,” an 8-foot 4-inch male nurse shark from Florida? They have both been spending their summers in the Dry Tortugas, Florida, for the past three decades.

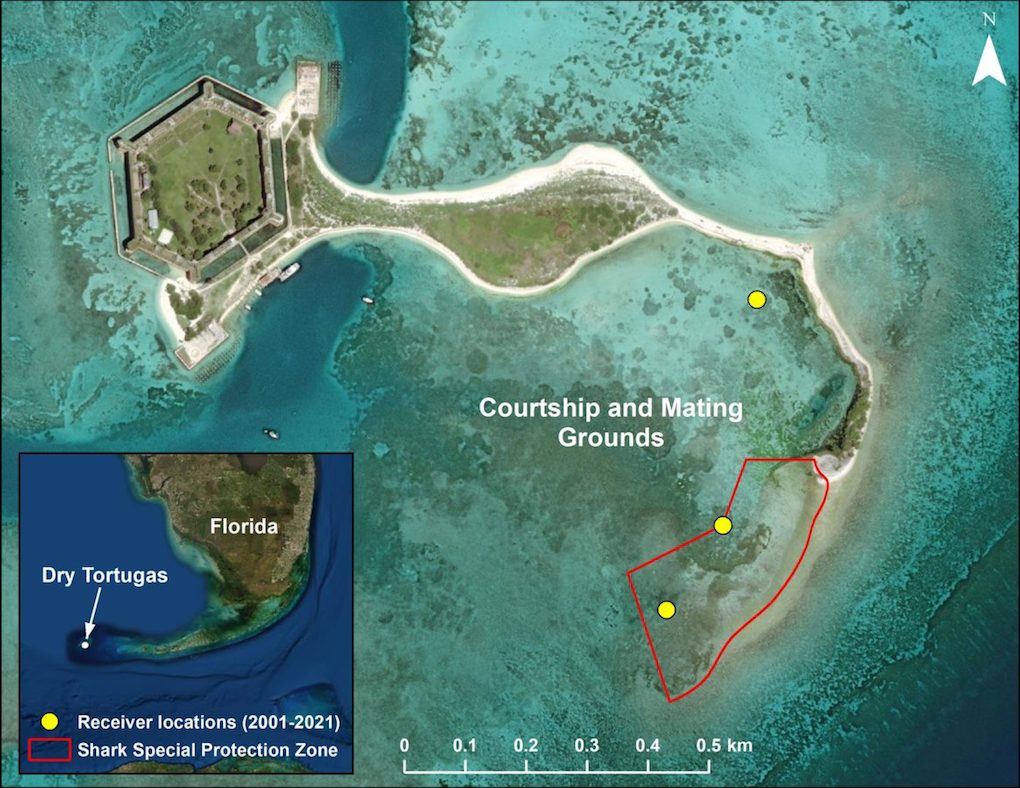

The Dry Tortugas, a remote island group and National Park located 70 miles west of Key West, has been known as a shark mating ground since the late 1800s, but came under direct study in the early 1990s when Wes started visiting the area with Dr. Jeff Carrier, Professor Emeritus at Albion College, Michigan.

In those early days, very little was known about shark mating behavior because it is nearly impossible to observe in the wild. Wes and Jeff spent their summers living out of tents in the sandy campground of Garden Key so that they could spend their days sweating in wetsuits under the harsh Florida sun, waiting to see interesting shark behavior. When the sharks would finally start mating, the scientists would snorkel out to them as fast as they could while pushing video cameras in underwater housings the size of suitcases.

Their video and observations revealed a surprisingly complex suite of behaviors and social interactions. They documented how male sharks compete, and sometimes cooperate with each other in pursuing females, and how female sharks appear to evaluate and choose their mates with much greater control than expected.

That pioneering work produced a number of scientific papers, National Geographic magazine features, and TV documentaries that laid the groundwork for what we know about shark courtship and mating today.

Later in the 1990s, Theo Pratt joined the research team, and she and Wes have been on site every summer since the turn of the century to document behavior and conduct a census of which individuals have returned each year. Many of those summers were spent on their own sailboat in the Tortugas anchorage as the Pratts began spending their years of “retirement” by conducting a summer of grueling fieldwork and compiling and analyzing data for the rest of the year.

I first joined the team when Jeff Carrier brought me to the Tortugas as his clueless, 20-year-old undergraduate research assistant in 1998, introducing me to the sharks, the Pratts, and sealing my fate as a “shark scientist” for life. I’ve been fortunate to return to the Tortugas in 13 summers since then and have managed to entangle several other Aquarium colleagues in the research, including Emily Jones, Dr. Ryan Knotek, members of our Animal Care team, and Connor White (currently a PhD student at Harvard University).

Today, we have several studies in process on this shark population that involve continued long-term monitoring as well as some of the most cutting-edge technologies available in marine research.

But this month marks the publication of a paper that summarizes findings that were ONLY made possible by continuous study every summer over thirty years. Thirty years of sunburns, skin rashes, cans of soup eaten out of a kayak, tents blown into mangroves, shark bites (that were very minor and well-deserved), scorpion stings (that were undeserved and required medical evacuation), boats blown off anchor in the middle of the night, boats that caught on fire, shocking discoveries, celebrations, rescues (of birds, sharks, manatees, and humans), sharks that returned from the dead, arguments, marriages, and a lot of missed birthdays.

Of course, none of these stories are conveyed in a scientific paper, and I won’t go into them here either. But I did want to summarize a bit of the history of this project (above) and highlight a few things that we report in our paper (below).

So, what have we learned in 30 years of studying these sharks?

1. This site is incredibly important to the sharks that use it; they show us that by using it year after year, for decades.

A single visit to this site during the month of June will show you that it’s unique. You’ll see that a large number of ~8-foot sharks aggregate in the warm, clear shallows here. You’ll see that female nurse sharks often shoal together in groups while males patrol the periphery and occasionally approach the females in an attempt to mate. If you stay long enough you may also see mating activity taking place, indicated by these large sharks rolling and splashing in the shallows.

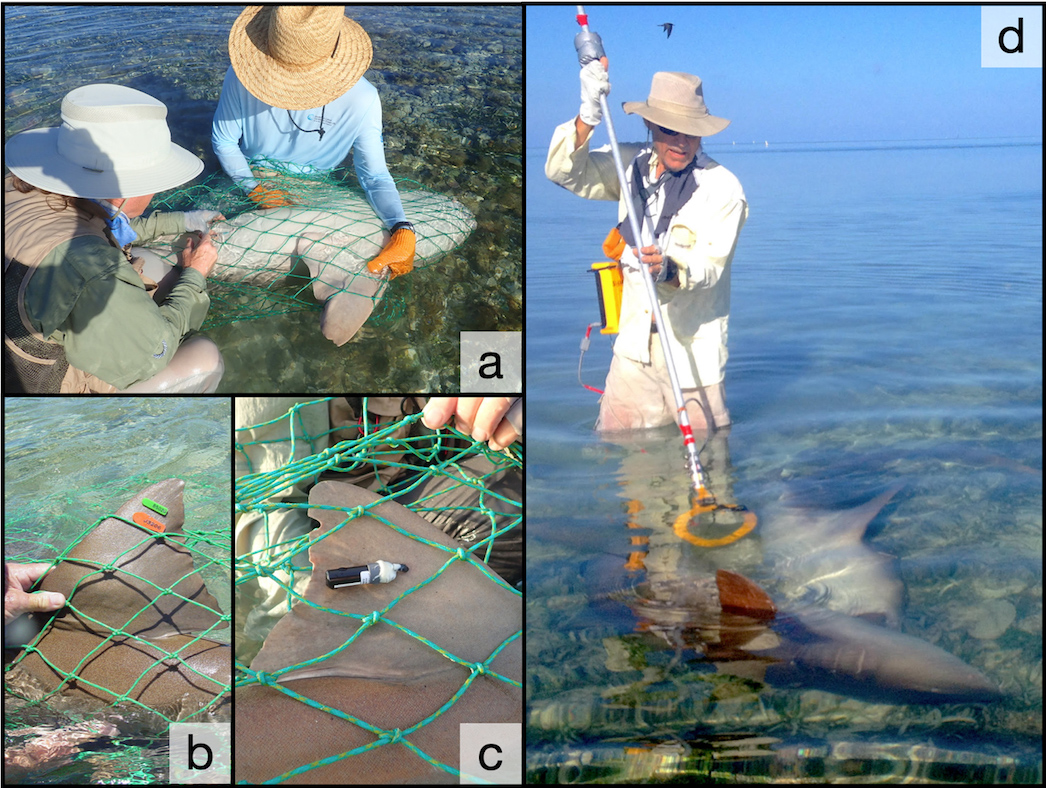

But what we have only been able to learn through our long-term study is that many sharks use this site year after year, for decades. We know this because we can identify each shark as a unique individual. We capture these sharks in giant dip nets and hold them in the shallows while we measure and tag them with a variety of tag types.

Each time the shark returns to the site after that, we have a chance to identify it based on several methods including:

- Direct observation of unique fin markings or colored tags that we place on the sharks’ dorsal fins.

- Reading a unique PIT tag (a tiny tag the size of a grain of rice that we embed at the base of the sharks’ fin and can be read with an electronic reader; your dog or cat likely has one of these embedded in its neck so a veterinarian can identify it if it ever gets lost or runs away because you’ve neglected it by reading long-winded shark blogs).

- Detecting a shark’s acoustic transmitter tag that sends out a unique pulse of “pings” every couple of minutes. These pings are recorded by a set of underwater stations anchored on the site that listen for tagged sharks 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

This combination of re-sighting methods has shown us that most of these sharks use this site repeatedly year after year. In fact, of the 118 sharks tagged from 1993 to 2014, at least 68% returned to the Dry Tortugas during the June-July mating season, and nearly all of them returned in multiple years.

Of the sharks that use this site repeatedly, a whopping 47 animals have used the site for at least ten years and, of those, ten individuals have used the site for 20 years or more! Four sharks have used this site over a period of 26 years or more with the longest running shark, a male nicknamed “Thumb,” returning in 16 different mating seasons over a 28-year period. WOW!

2. These sharks live longer than anyone thought.

The scientific literature says that nurse sharks live up to 24 years of age. That was before our paper was published. Not only have many of our sharks lived longer than 24 years, but several have been reproductively active ADULTS for longer than that. If we conservatively estimate that these sharks become sexually mature in their mid-teens, then we can easily deduce that nurse sharks live at least into their 40s.

Of the 28 sharks that have been in the study for at least 20 years, nearly half have been seen mating in the last two years, indicating their continued survival and use of the site. It’s very likely that the maximum age for this species will continue to increase in the coming years based on sightings of sharks in our study.

3. Males and females use the site very differently during the mating season, and also throughout the year.

Males come back to the mating ground every summer, arriving in April and May, whereas the females arrive in June. Upon arrival, the females spend more time in the study site than the males, resting for long periods and often shoaling together in the shallows. Males tend to visit the site for shorter periods, coming into the shallows to approach—and sometimes attempt to mate with—the females before moving back to deeper water. Males and females both tend to disappear from the site in July, but the females often return in the fall, likely using the shallow, warm waters to speed up the development of their embryos before they give birth in late October through early December.

4. Females never reproduce in consecutive years, but usually reproduce on a two- or three-year cycle.

When Wes and Jeff first started this work, they often heard the critique that they couldn’t report on female reproductive cycles because they couldn’t prove that the females on site were pregnant. This criticism has been overwhelmed by 30 years of data. Although females return to this mating site repeatedly for decades, they NEVER return in two mating seasons.

What does this mean? It means that the females that mate here are indeed getting pregnant, and likely carrying their pups to term, and they are physiologically incapable of reproducing two years in a row. In fact, sometimes they require an extra “resting year” and will return to mate after three years instead of two.

5. Females can switch back and forth between a two- and three-year cycle, which has real implications for lifetime reproductive output and shark conservation.

Although previous studies have shown that there can be both two- and three-year reproductive cycles within the same shark species, ours is the first to show that you can have these different cycles within the same individual female. We have observed our females switching from a two- to a three-year cycle and sometimes switching back. Overall, this means that our females are reproducing about 11% fewer pups over their lifetime than what would be expected from a strict two-year reproductive cycle.

This finding could have broad implications if it happens in other species thought to have a biennial reproductive cycle, and the cycle-switching would be impossible to detect in traditional studies that require examining the reproductive tracts of dead female sharks. This discovery was only possible because of our long-term study of living sharks in the wild.

6. Specific courtship and mating grounds can be critically important for shark species and may be particularly vulnerable to climate change.

Our past work has shown that these sharks, once thought to be sedentary “couch potatoes,” will migrate as far as Tampa Bay, South Carolina, or the Bahamas, and still return to the Tortugas in the summer to mate. This suggests that this site is crucial to these long-lived animals, and there may very well be similar crucial sites that are used for reproduction by this and other shark species around the world.

Wes and Jeff have already documented the vulnerability of this site to human boat traffic. Due to their work with the National Park Service, the site was established as a Marine Protected Area (MPA) in 1998, the only MPA in the world dedicated to protecting a shark breeding ground.

What has become apparent over the course of our study, and particularly in 2022, is the vulnerability of this site to climate change. The Dry Tortugas courtship and mating ground is a shallow, sandy embayment protected by low lying islands that we have seen shift repeatedly over the years. Hurricane Ian appears to have produced the biggest change to this habitat in at least 70 years—and possibly longer—opening up a huge gap between Bush and Long Keys that may dramatically increase waves and water flow in the area.

What will this mean for the sharks and their use of this site? We hope to continue our study in the coming years to find out.

We would like to thank the National Park Service and their staff for over 30 years of support and assistance, without which this study would not be possible.