Please Note: Our Box Office is currently closed for renovation. We recommend purchasing tickets online in advance to expedite your entry into the Aquarium. Tickets can also be purchased onsite at the Information Desk in the lobby today.

There and Back: Year Two of Albie Tagging and More Migration Insights

By New England Aquarium on Tuesday, March 05, 2024

By Edward Kim, Caroline Collatos, and Jeff Kneebone

Another fall gone by, and a second season of false albacore acoustic tagging is officially in the books for Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life researchers. False albacore, or “albies,” are popular among recreational anglers from Massachusetts to North Carolina, but little is known about this species or its fishery and there has only recently been discussion of any regulations. To assist in proactive management, we’ve been conducting research in partnership with the American Saltwater Guides Association (ASGA) to track the movements of these speedy fish. Check out our past stories from last season’s field research in Nantucket Sound and tracking albies down the coast to learn more about the project.

Armed with knowledge and experience gained in our first year of acoustic tagging and an expanded acoustic receiver array, we once again enlisted the help of ASGA local charter captains and volunteer anglers to catch and tag albies in Nantucket Sound. After numerous tagging trips from August to October 2023, we finally reached our goal of 97 transmitters deployed—a testament to the skill and commitment of our fishing industry partners.

When acoustic receivers were hauled and downloaded in early November, we were immediately excited to see data from 102 tagged false albacore, including 11 fish tagged in 2022 that returned to Nantucket Sound in 2023! Like what was seen in 2022, tagged fish roamed all throughout the receiver array from the end of August to the beginning of November, with some fish still lurking on the day the receivers were removed for the season!

Tracking False Albacore

Movement paths of 91 tagged false albacore and 11 returning false albacore throughout fall 2023. Black triangles represent receiver locations.

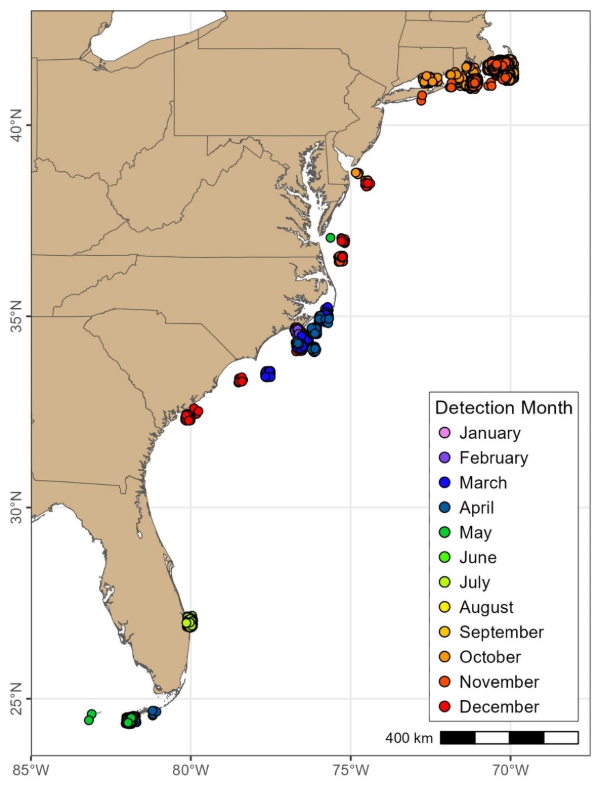

In addition to the data we collected with our own acoustic receiver array, recent data uploads to the Atlantic Cooperative Telemetry (ACT) Network revealed exciting news on the migration paths of the 2022 cohort of tagged albies. In our last update, we reported that these fish were detected in North Carolina and the Florida Keys through spring 2023. Since then, we’ve received data filling in more states along the coast from New Jersey to Georgia, giving us a better understanding of the journeys of our sunshine-seeking albies. The latest detections in June and July occurred in Florida and show that some of our migrants enjoy the warmth of the south well into the summer months.

The 11 returning fish completed quite the round trip, with nine last detected in Florida and two last detected in North Carolina before finding their way into Nantucket Sound. Amazingly, the fastest migration time from Florida back to Nantucket Sound—a distance of over 1,100 miles—was just 40 days, showcasing just how quickly these fish can swim when they have somewhere to be!

This migration circuit combined with the newest detections along the coast further strengthen the case that false albacore exist as one population along all states from Massachusetts to Florida. In terms of management, this exchange of fish means that fisheries at one end of this range have the potential to impact fisheries at the other end and vice versa. Furthermore, any prospective actions taken to regulate false albacore by state, such as the rule recently proposed and passed in North Carolina, should be coordinated to achieve maximum impact across the population.

For now, we’re anxiously waiting to see where the freshly-tagged albies will migrate to during the winter months and wondering if any familiar faces show back up for another visit to our waters in summer 2024.

Special thanks to the ACT Network and the various owners of the arrays who provided data and made this work possible: the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy and Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries; the Atlantic Shark Institute; NOAA Fisheries Northeast Fisheries Science Center; Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection; Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management Division of Marine Fisheries; University of Massachusetts Dartmouth – School for Marine Science & Technology; Stony Brook University; the Applied Ecology Lab at North Carolina State University – Center for Marine Sciences & Technology; the South-east Zoo Alliance for Reproduction & Conservation and North Carolina Aquariums; the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and Coastal Carolina University; South Carolina Department of Natural Resources; Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission; and the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust, Carleton University, University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission.