The Hammerhead Sharks of Peru’s Tropical Sea

With MCAF's help, conservation organizations from Peru and Costa Rica team up to further the study of hammerhead sharks.

By New England Aquarium on Wednesday, December 11, 2019

Note – published in Dec 2020 but backdated for sequencing purposes.

This post is one of a series on projects supported by the New England Aquarium’s Marine Conservation Action Fund (MCAF). Through MCAF, the Aquarium supports researchers, conservationists, and grassroots organizations around the world as they work to address the most challenging problems facing the ocean.

In this piece, Mariano Cabanillas-Torpoco describes a learning exchange between the Peruvian non-profit organization Planeta Oceano and Misión Tiburón Costa Rica. In January, Mariano a scientist working with Planeta Oceano and his colleague Claudia Ampuero, traveled to Costa Rica to learn shark tagging techniques from Misión Tiburón co-founders Andres Lopez and Ilena Zanella, so as to bring that knowledge back to Planeta Oceano’s hammerhead shark project. MCAF helped to support this learning exchange as well as a number of other shark and ray conservation efforts over the years led by Planeta Oceano and Misión Tiburón.

Para español, haga clic aquí versión de esta publicación.

By Mariano Cabanillas-Torpoco

Background

There is a serious problem: Shark populations are being seriously affected worldwide by activities related to fishing (such as overfishing, ghost fishing, finning, among others). Peru, positioned among the 10 main fishing countries in the world, is no stranger to this problem.

The Tumbes region, in the north of Peru, is known for its paradisiacal beaches and delicious seafood. The region is also home to many of the 68 species of sharks recognized in Peru, among them, the mythical and majestic hammerhead shark. (AKA “Marti” for tiburon martillo, the species’ name in Spanish). The presence of this species in our waters is something that many Peruvians are unaware of. It is possible that the sea of Tumbes is a breeding areas for this species. This is suggested by the fact that many artisanal fishermen in the region land large numbers of hammerhead sharks, most of them juveniles. If we want to protect the hammerhead shark we need to know more about them and their habitat. This is why we have a launched a study of their distribution and abundance.

At Planeta Oceano, an organization that works for the conservation and restoration of the Peruvian marine and coastal environments, we have a talented team of professionals to carry out the study of the spatial ecology of our beloved hammerhead shark. Through our acoustic telemetry study, we are working to answer questions such as “Do the “martis” always stay in the Tumbes region?”, “Do they only go there to give birth?” or “is it perhaps a foraging area?” In carrying out the study, we have had numerous collaborators. We obtained tags and acoustic receivers from Ocean Tracking Network and MigraMar. For field support, we have the continued collaboration of fishermen in the region who share our interest in marine conservation. Marine scientists, Ilena Zanella and Andrés López from Misión Tiburón, a Costa Rican NGO that promotes research, management and conservation of sharks and other marine species, offered to train us in acoustic telemetry techniques at the Golfo Dulce Hammerhead Shark Sanctuary in Costa Rica. Likewise, our friends from the New England Aquarium joined us in this task when they notified us that we were awarded with a grant from their Marine Conservation Action Fund (MCAF), which gave us resources to obtain more acoustic labels, travel to Costa Rica to be trained by Misión Tiburón and obtain the PADI Open Water certificate, as well as financing trips to the sea to continue investigating hammerhead sharks.

Let’s Do It

As Claudia Ampuero (my project partner and great friend) and I boarded the plane from Lima to Costa Rica our spirits were high. Costa Rica welcomed us with open arms and in Guanacaste we were excited to meet up with Ilena and Andrés. We went over our schedule and then it was time to sleep and recharge, because the next day began a week as intense as it was rewarding.

At the field station, Ilena and Andrés gave us an introduction to acoustic telemetry, indicating how it works and detailing the use and handling of its components. We learned about the operation, assembly and disassembly of the receiver, as well as how to use the software that interacts with the receiver via Bluetooth. We also received guidance on the installation at sea, about the activation and deactivation of the acoustic tags as well as setting the emission interval with consideration for the type of species and the environment. We also learned about a fundamental part – implanting the acoustic tags in sharks. For this delicate operation, Ilena and Andres lent us hammerhead shark molds to practice suturing. We spent a lot of time exercising this skill in order to become fairly competent shark surgeons.

Then came the long-awaited outings to the sea. We traveled from the north to the south of the country, along the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica. We marveled at all the beautiful landscapes as our hosts told us about the flora and fauna of their country. In every word they said to us, we felt all the passion and love they have for their country.

At the Golfo Dulce Hammerhead Shark Sanctuary we put into practice what we learned at the field station. The first thing to take into account, as Ilena and Andrés told us, is that teamwork and communication is essential, since we are collecting data from a live shark that has to return to the water in optimal conditions. Thus, we begin with the tagging process:

Once captured, the shark is brought on board with a tool similar to a butterfly net but much larger to reduce the stress of handling the animal. The shark is held firmly but carefully and is oxygenated with sea water. Then the shark is placed in an area on the boat equipped for taking measurements, fixing numbered marks (for a possible recapture) and implantation of the acoustic tag. While these procedures are happening, we are always considering the status of the shark and release it as quickly as possible so that it can return to the sea in good condition. Through going through this process, Claudia and I learned about shark telemetry and sampled our first sharks under the supervision of two great researchers. Along the way, we experienced spectacular sunrises and were sheltered by infinite starry skies.

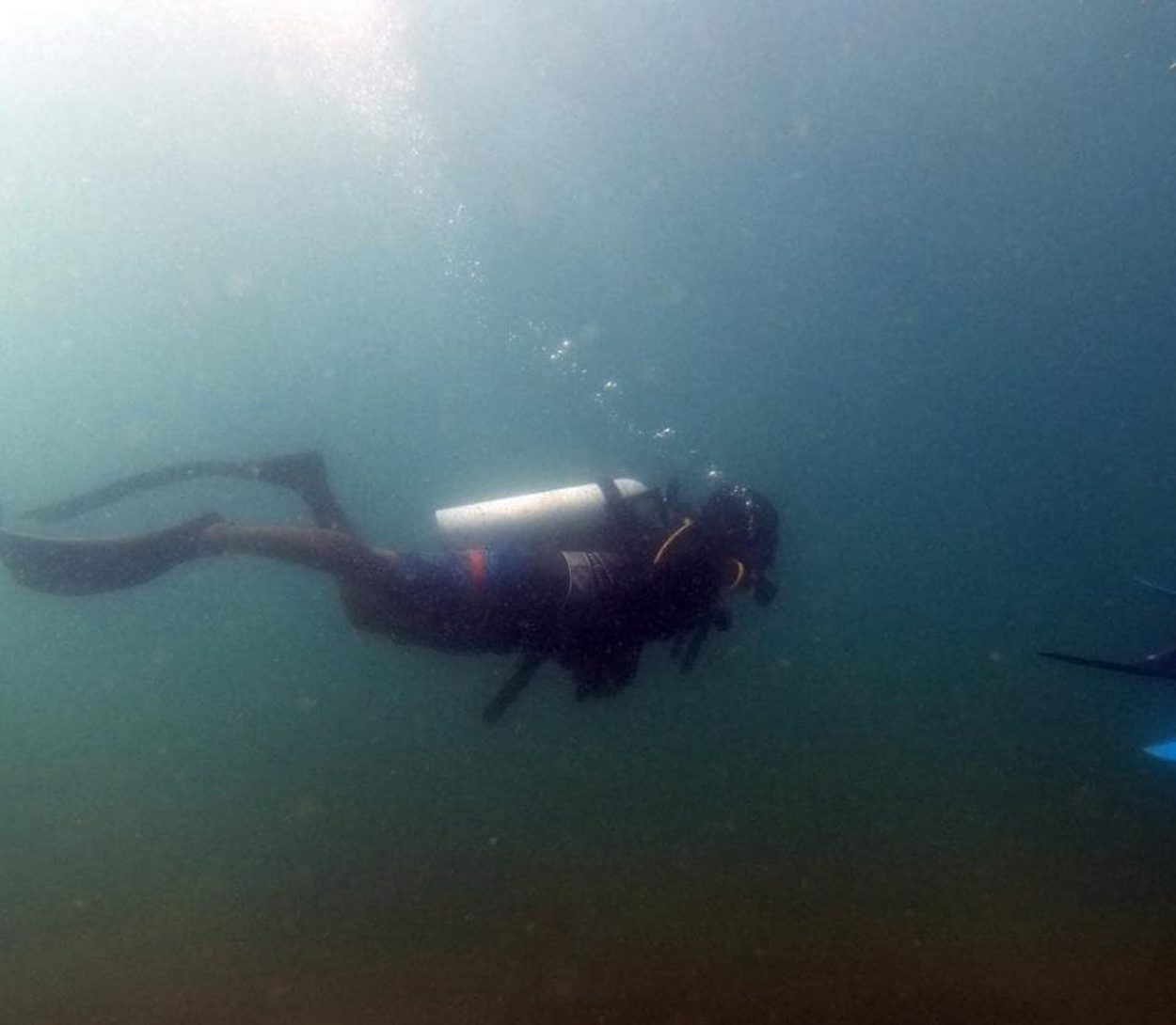

Another objective of our trip was to earn our PADI open water scuba diver certificate, a first step to obtaining certification as a scientific diver. In Peru, the artisan divers of the Paracas National Reserve taught me how to dive. Although they taught me a very primitive method (because that’s how they do their work) they did it with great patience and caution. This is how I discovered the fascinating underwater world and fell in love with it. Now that I have my PADI certificate I can dive all over the world. I must emphasize that diving in Costa Rica was a privilege, it gave me the wonderful opportunity to meet sharks up close. Seeing them move with such harmony, their gentleness and beauty changed something deep inside me, and I fell even more in love with the sea. A deep joy shelters me as I think of returning to the water, and seeing the sharks again. I will be submerged not only in the sea, but also in happiness, and this kind of happiness is one of the most sublime, magical and essential feelings of one’s lifetime.

This trip changed me. Thanks to the support of the New England Aquarium’s Marine Conservation Action Fund, we were not only technically and scientifically trained, but we grew as people, we broke down barriers, overcame some fears, and became more passionate about what we love.

These experiences and learnings make me say with great confidence that the sea transformed me.

Today I know my personal north always points towards the sea.