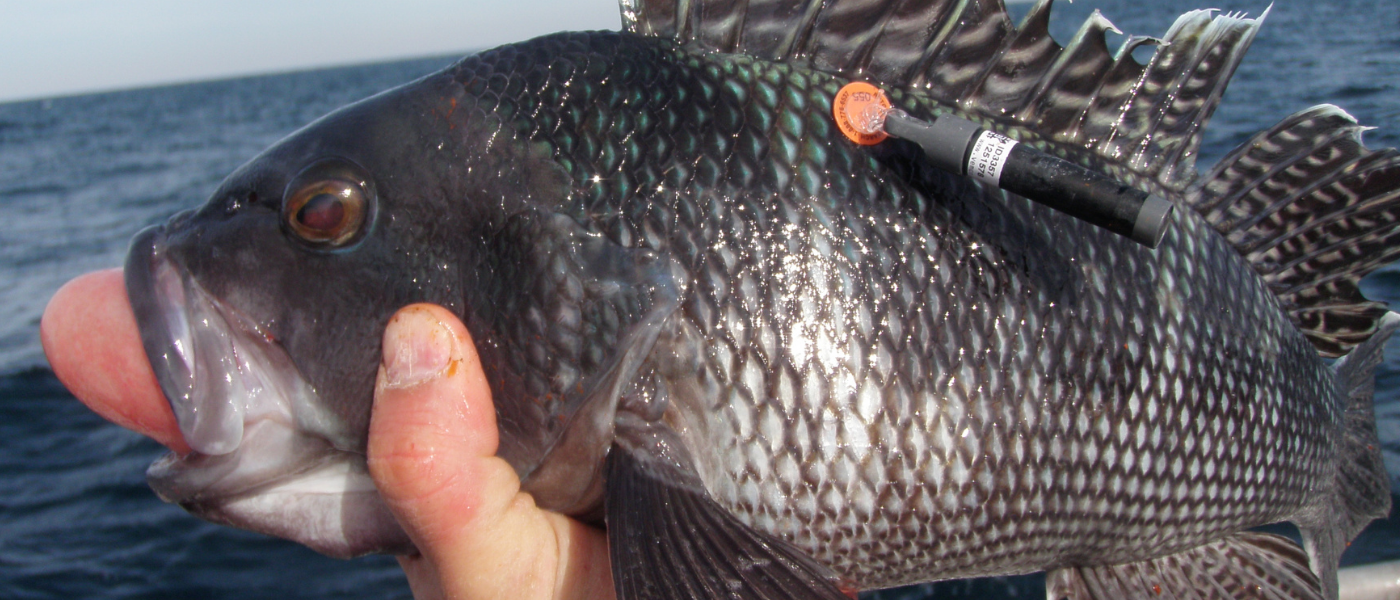

Sweet relief: Increasing the survival rate of black sea bass through swim bladder venting

By Jeff Kneebone, PhD on Monday, November 08, 2021

The black sea bass (Centropristis striata) is a small, reef dwelling fish species commonly found along the US east coast from Florida to Maine. Over this broad area, black sea bass are frequently caught by recreational rod and reel fishermen over a range of locations and water depths from the shore to offshore shipwrecks over 200 feet deep. Each year in this popular fishery, millions of black sea bass are caught and released by recreational anglers either in compliance with recreational fishing regulations such as minimum retention size, daily possession limits, or closed fishing seasons, or simply because anglers do not wish to keep the fish. While catch-and-release is often considered a responsible conservation strategy, some released fish can die from stress or injuries that occur due to aspects of the capture and/or release events.

When black sea bass are reeled up from the bottom of the ocean they experience a reduction in pressure, which results in the rapid expansion of the gases in their body (if you’re a SCUBA diver, think of the ‘bends’). One of the places where the expansion of gas is most evident is in their swim bladder, the internal organ fish use to regulate their depth. Unfortunately, when black sea bass are reeled to the surface from depths greater than around 100 feet they cannot expel gases from their swim bladder faster than they expand. Sometimes the pressure in the body cavity becomes so great the stomach is forced out the mouth – a phenomenon known as stomach eversion. Even if a black sea bass doesn’t experience stomach eversion, their over-inflated swim bladder, acting like a balloon, often prevents them from being able to swim back down to the bottom of the ocean after release – which is not good news for a fish that lives on or near the bottom!

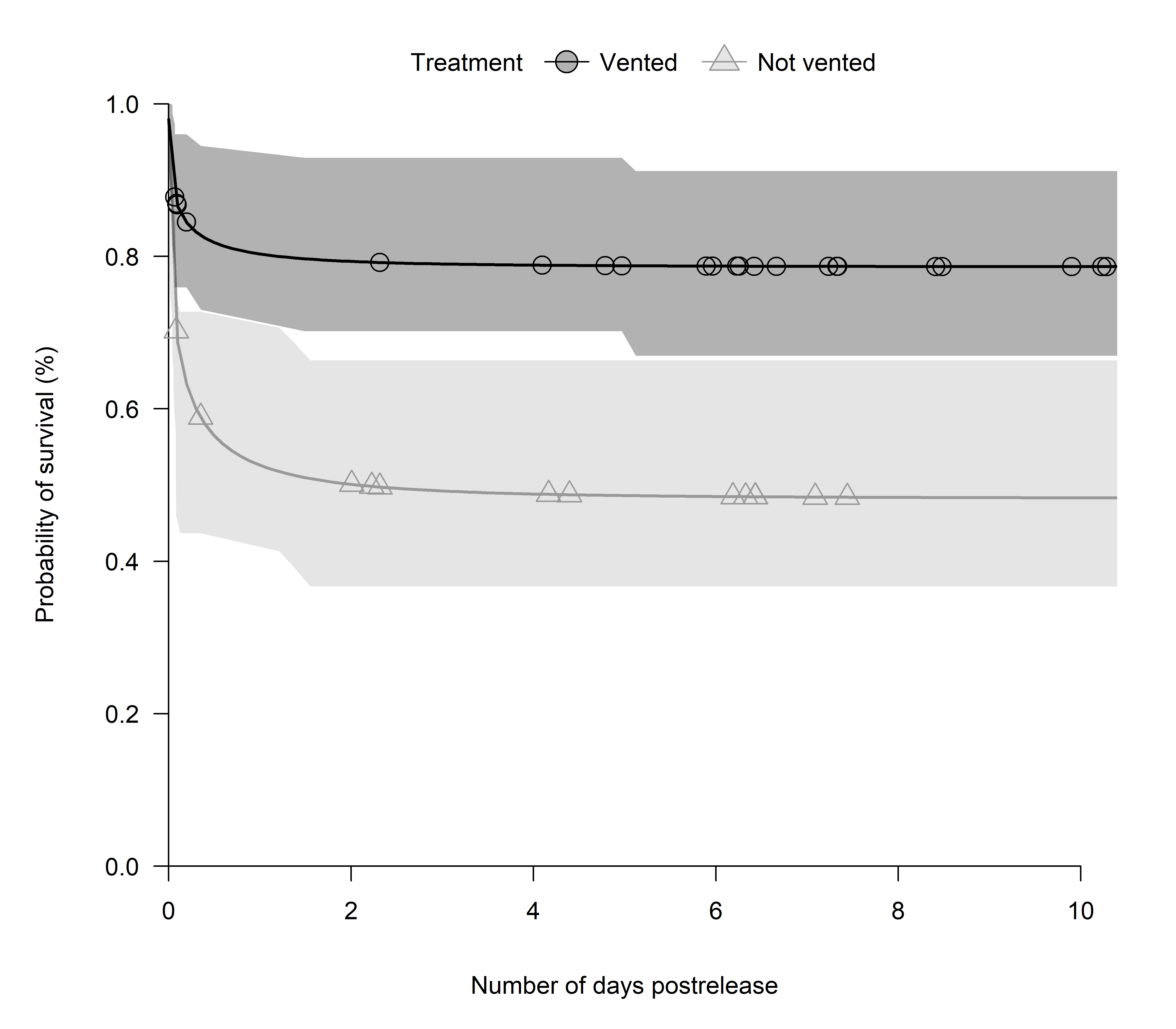

Working with a team of researchers led by Dr. Douglas Zemeckis of Rutgers University, Anderson Cabot Center scientists helped conduct a tagging study off the coast of New Jersey to better understand the impacts of pressure-related injuries – known as barotrauma – on black sea bass survival following catch and release by recreational anglers in 150 to 220 foot depths. The team found that 95% of the black sea bass captured in these deep waters experienced some form of barotrauma, including swim bladder expansion and stomach eversion, which was the primary cause of death after release. Fortunately, the team also found that puncturing the swim bladder with a small hypodermic needle to release expanded gases – a process known as ‘venting’ – not only allowed released black sea bass to swim back down to the bottom, but also increased the chance of survival from 50% to 80%!

Although these findings showed the clear benefit of venting to black sea bass survival, it’s very important to note that when done incorrectly venting can sometimes have the opposite effect and actually cause more injury, and sometimes death. For this reason, our research team recently published a fact sheet describing proper techniques for venting black sea bass to ensure that the procedure promotes – and does not impair – black sea bass survival. We hope that recreational fishermen will read our fact sheet and learn how they can do their part to maximize the chance that any black sea bass they release survives to spawn another day.

You can also read more about our tagging study and the impact of rod and reel capture on black sea bass survival in a scientific journal article that you can access for free here.

Funding for this research was provided by the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s Collaborative Research Program.

Research team: Dr. Douglas Zemeckis (Rutgers University Cooperative Extension), Dr. Jeff Kneebone, Dr. Connor Capizzano, Dr. John Mandelman (Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life), Eleanor Bochenek (Fisheries Cooperative Center, Rutgers University), Dr. Olaf Jensen, Dr. Thomas Grothues (Rutgers University), Bill Hoffman and Dr. Micah Dean (Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries)