Southern New England Surveys, Take One

By New England Aquarium on Monday, March 07, 2022

By Kate McPherson

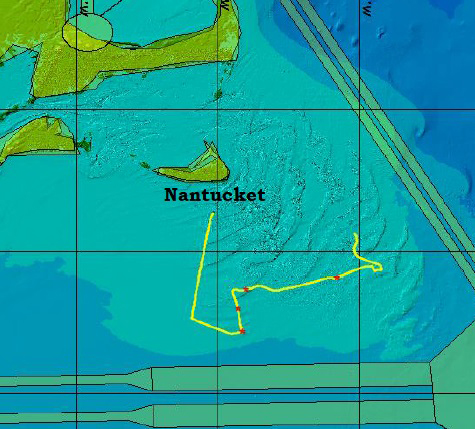

The area south of Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard has increasingly been documented as an important North Atlantic right whale habitat, but to date, the majority of survey effort in this region has been aerial. Since the whales are often found quite far offshore, this is a logical means of monitoring the region; however, there are certain data collection activities that cannot be achieved from a plane. Getting detailed photographs for health assessments, as well as biopsy samples and poop samples, can really only be accomplished from a vessel, and that is precisely what our team set out to do this January aboard the 80’ charter fishing boat Helen H. We gathered in Hyannis, MA, on Cape Cod to begin the very first New England Aquarium vessel-based surveys for North Atlantic right whales in the waters of southern New England.

The buzzing of phone alarms woke us at 3:45 a.m. to the dark and chilly Monday morning when our team was slated to set out on our first survey day. Though it felt strange to be steaming out to sea in complete darkness, it was necessary to make the most of our day on the water since we had a considerable distance to travel to the area where we hoped to find right whales. It wasn’t just the distance that we had to cover that was going to take time—we would be traveling through the Dynamic Management Area (DMA) triggered by the presence of right whales, which meant our vessel would travel at 10 knots or less for much of the day. Anyone who lives in New England can tell you that the month of January is not known for long days, so we knew we would be lucky to work until 4:30-4:45 p.m. before losing daylight and our ability to keep a watch out for whales.

As we set out from the dock at 5 a.m., our veteran team members quickly worked out a plan for storing and organizing our equipment among the benches in the cabin, then moved several reference binders and our field computer to the wheelhouse where the data recorder would be based. Everyone was outfitted with a pair of binoculars and a float coat or suit, which would help insulate us from the cold January air while on watch (and keep us afloat in the unlikely event that we ended up in the water).

Daybreak arrived to signal the start of our watch, and it was time to look for whales. Leaving behind the relative warmth of the cabin to step out onto the breezy upper deck was a bit of a shock at first, but thanks to the many layers we wore, it soon became bearable. We decided on a rotation schedule that would allow people to alternate between standing on watch at the front of the boat for an hour and working inside the wheelhouse as the data collector, or returning to the main cabin for a brief rest period (though we found that much of that rest time was spent climbing in and out of various layers of sweaters, fleeces, jackets, and float suits to avoid overheating).

Throughout the morning, we continued to rotate positions, and while a few flukes were sighted in the distance, they were not re-sighted even after waiting in the last known area for over half an hour. We finally caught a break around midday with help from our colleagues at the Center for Coastal Studies, who were flying an aerial survey in the same region. Following coordinates forwarded to us from the researchers in the plane, we arrived on scene to find two right whales swimming somewhat erratically just below the surface. Cameras came out of their protective storage cases and we began to document as much as possible while trying to track alongside the whales. While the whales’ behavior limited our ability to get the thorough photo-documentation we typically aim for, we were able to get solid identification shots and later confirmed that one of the whales we photographed in that pair, Catalog #4220 had not been photographed from a vessel since he was a calf in 2012!

The other two whales we photographed that day were not seen by the plane, so although we had few sightings, each was particularly informative and well worth the time spent finding them. And of course, any day spent on the water with whales is a good day in our books.

The weather was working in our favor again later that week, so we decided to take advantage of the relatively calm sea state forecast for Thursday. Once again the team rallied in Hyannis and set out from the dock bright and early in the hopes of finding more right whales. Since the air temperature had dropped into negative digits, we changed our rotation schedule to allow people shorter periods of time standing with their faces into the biting wind. We also decided to post someone looking out from the stern of the boat where they would be able to keep an eye on our wake in case a whale decided to surface after we passed by. This proved to be a wise choice as whales were spotted from the rear of the boat; unfortunately, they exhibited the same long dive times that we had encountered on Monday, and we weren’t able to photograph them.

Our persistence paid off around 3:30 p.m. when a group of right whales was spotted rolling and generating whitewater in the distance, the telltale signs of a Surface Active Group (SAG). We approached the group slowly and began to document each individual as they came to the surface, celebrating our luck at finding the proverbial needle in the haystack. Several more blows were sighted within a mile radius, and we were certain this was the highlight of our day. Then to our surprise and delight, a pod of common dolphins appeared, swimming close enough to the vessel for us to see that there were several young calves in the group! The dolphins stayed just long enough to check out our crew and the active right whales, then swam off as quickly as they had arrived.

We continued to collect photos of the whales for over an hour until we began to run out of daylight. Knowing we had a long trip ahead of us, and wanting to be clear of the right whales before we could no longer see them, we began the slow journey back to port. During the ride home, people filled out data sheets, backed up images, submitted our sightings data to WhaleMap, and organized equipment in preparation for a swift departure once we reached the dock. We returned to Hyannis a little after 10 p.m., tired but still excited from our day’s success.

Fieldwork involves an enormous amount of preparation, and even the best laid plans can be waylaid by weather, crew illness, and other unforeseen events. This is challenging enough in regions where field work has been conducted for decades, but when you’ve set your sights on a new survey region, the stakes feel even higher. Consequently, the completion of the first leg of our southern New England fieldwork felt like a great accomplishment despite weather limiting us to only two days on the water. We photo-documented 10 individual right whales over the two trips, and caught fleeting glimpses of several more. Our team was able to photograph an individual who hadn’t been documented from a vessel in ten years, and 7 of the 10 whales we photographed were only seen by us that day. After two days of surveying the waters of southern New England, our team feels even more prepared to embark on the next half of our field season and collect even more valuable data on this critically endangered species.

We’re extremely grateful to Irving Oil for partnering with us on this critical research since 1998! We are also grateful to Irving Oil and the Island Foundation for allowing us to operate during these financially challenging times. This work would not be possible without their generosity!