Scooping the Poop and Pinching the Skin

Researchers with the Right Whale Research Program at the Anderson Cabot Center were key members of two research cruises in the Gulf of St. Lawrence this summer. These are the updates from the August cruise.

By Monica Zani on Thursday, September 26, 2019

Offshore fieldwork comes with a myriad of logistics, and with each logistical arrangement, the opportunity for success and for failure. There are things we have absolute control over such as testing and packing our equipment, applying for permits, creating schedules, organizing food shopping, and loading the vessel. To make sure everything is in place and the work begins on time, the planning starts six to eight months in advance with monthly planning meetings, purchasing lists, and many, many checklists. However, the list of things we cannot control is even longer and can seem endless at times. We cannot control the weather (as much as we want to), maintenance issues, permit delays, software bugs (for as much as we bang our heads on the wall), and equipment failures. On the worst days, you feel defeated, exhausted, and a little beat up. But on the best days …. well, those are the days when we rejoice while scooping poop from the ocean and cheer aloud when the collective teamwork on the vessel makes obtaining a biopsy sample possible.

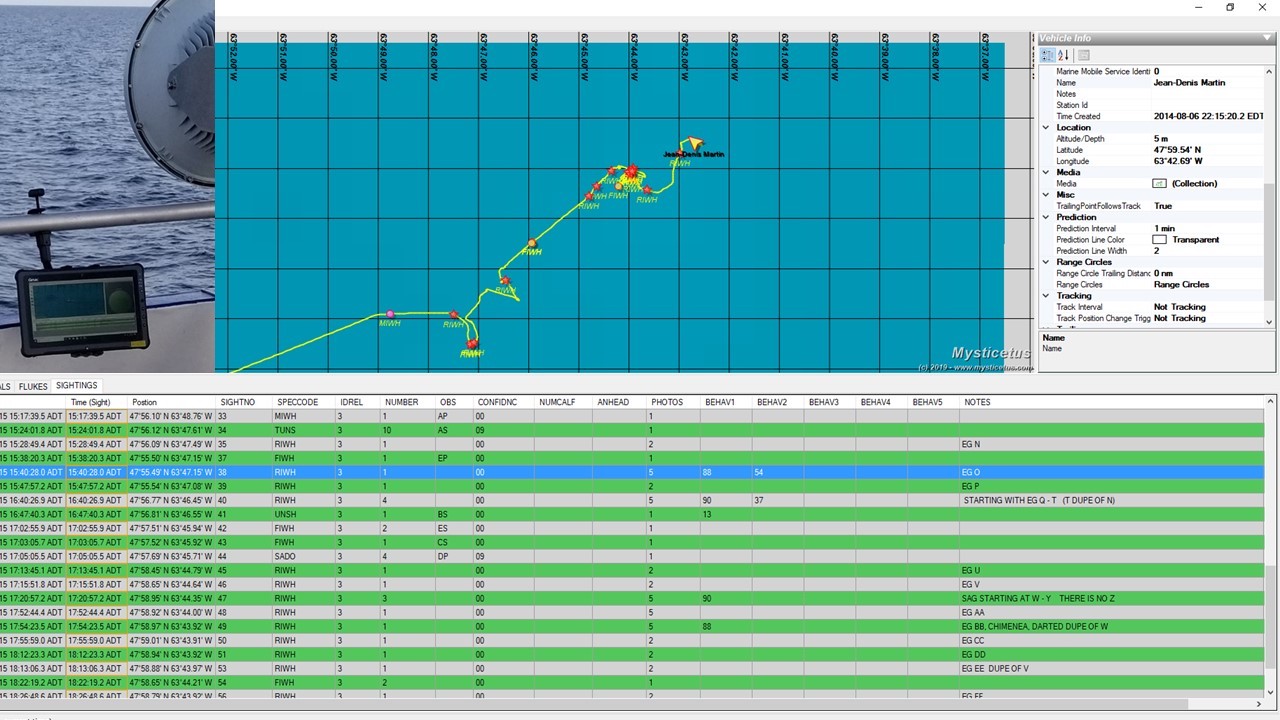

For each day we spend at sea, we are collecting priceless data. We are collecting survey effort data the entire time we are “on watch” (two observers maintaining constant lookout for marine life at the surface). We are collecting valuable photographic data each time we document right whales, and this data is used for health assessment and scar analysis, and also is incorporated into the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium Identification Database to better track and understand the population.

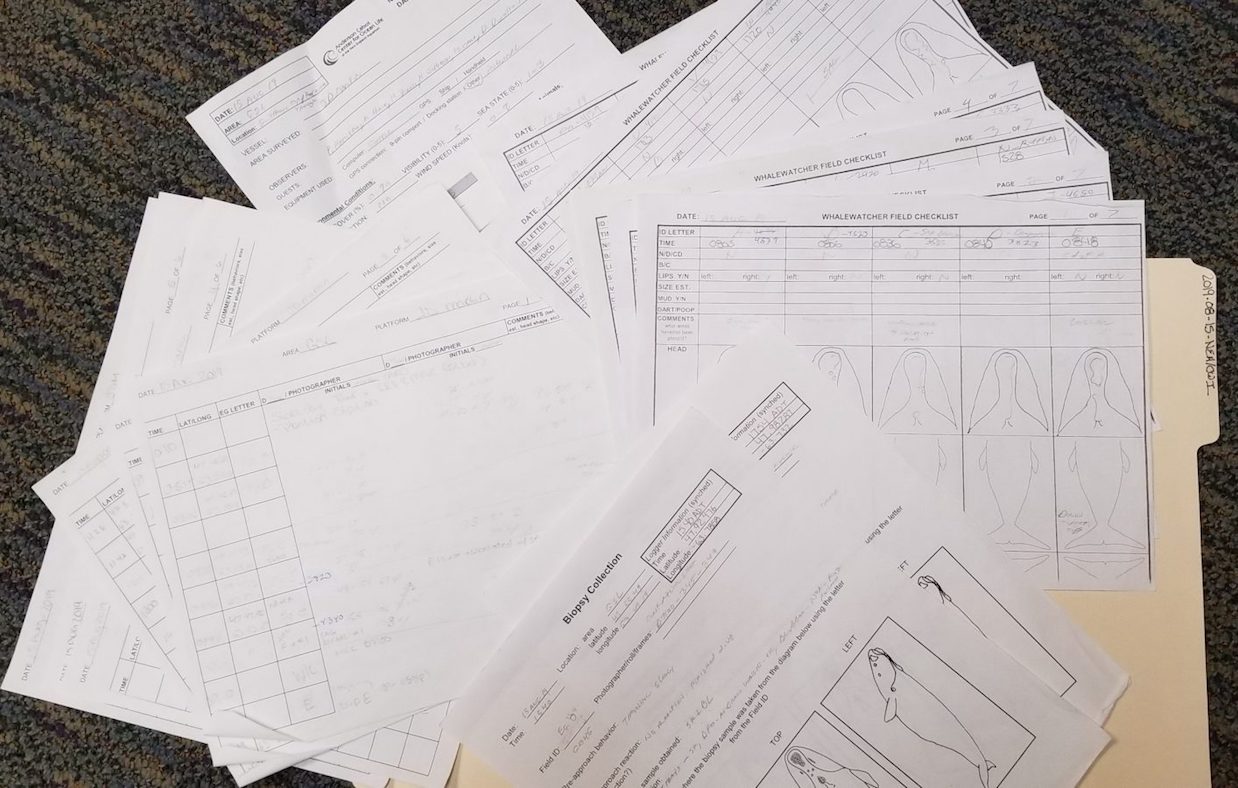

Over time, this becomes our offshore norm: you wake up about 6 a.m. or earlier, eat breakfast before heading up to the wheelhouse to get the equipment packed and computer up and running. You pack cases (cameras, clipboards, binoculars, water bottles, and sunscreen) and head to the roof, where you will remain as a team the rest of the day if there are right whales (rotating in and out for some quick breaks and maybe a nap if you are lucky). The day continues until you begin to run out of daylight (12-14 hours later) and you pack up all the equipment and head down to the wheelhouse. Once below, the team begins to clean equipment (the marine environment is harsh on electronics), tidy up data sheets, back up electronic data, and report all right whales sightings to the proper entities (often fighting satellite and/or cell service for a poor internet connection to make it happen). Finally, you eat some dinner and hope to be in your bunk before 10 p.m., since the night watch (looking out for other vessels) begins at 11:30 p.m. (in rotating two-hour intervals). This routine continues for as long as you remain at sea. Some days, however, there is a break in the routine – a cool sighting of a bird or shark that sparks conversation, an interesting cloud formation, an amazing sunrise or sunset to swoon over, or the fruition of the ultimate challenge … collection of a biological sample.

The list of events that can alter our ability to be successful in biological sampling is long. With skin and blubber collection (biopsy darting), it can include frustrating equipment failures, poor communications, a whale’s behavior (avoidance), the wind, the state of the ocean, timing (the whale is gone before we get into place to attempt to sample), or the darter simply misses the shot. With fecal collection, the process can be just as frustrating. Often we see defecation in a SAG (Surface Active Group), but the sample gets destroyed (broken up and sinks) by the whale activity before we can attempt to collect it. Other times, we can’t physically get in the right place to collect the sample or we can’t find the sample once we arrive on location. Other times, the sample is so small we can’t collect enough to make it valuable (and we only need a small bit to be valuable). Some days, however, everything lines up perfectly! Because biopsy and fecal sampling are real all-hands-on-deck situations and the entire team works hard to make the collection happen, the success is shared by everyone onboard, and the triumphant feeling that comes with it is worth all the frustration.

Check out the video below to see Monica collect a sample using the crossbow!

Collecting a biopsy sample from a right whale

This is how researchers collect a biopsy (skin and blubber) sample from large whales!

This work is made possible in part by the generosity of Irving Oil, lead sponsor of the New England Aquarium’s North Atlantic Right Whale Research Program.