Scenes from a Right Whale Entanglement

By Kelsey Howe on Friday, February 11, 2022

By mid-July 2021, our two-week right whale research cruise was fully underway in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. We had been out at sea for the past two days photographing dozens of right whales every day, as well as conducting various other forms of right whale research. On July 13, we woke up to calm seas, right whales all around, and a beautiful sunrise to start our day.

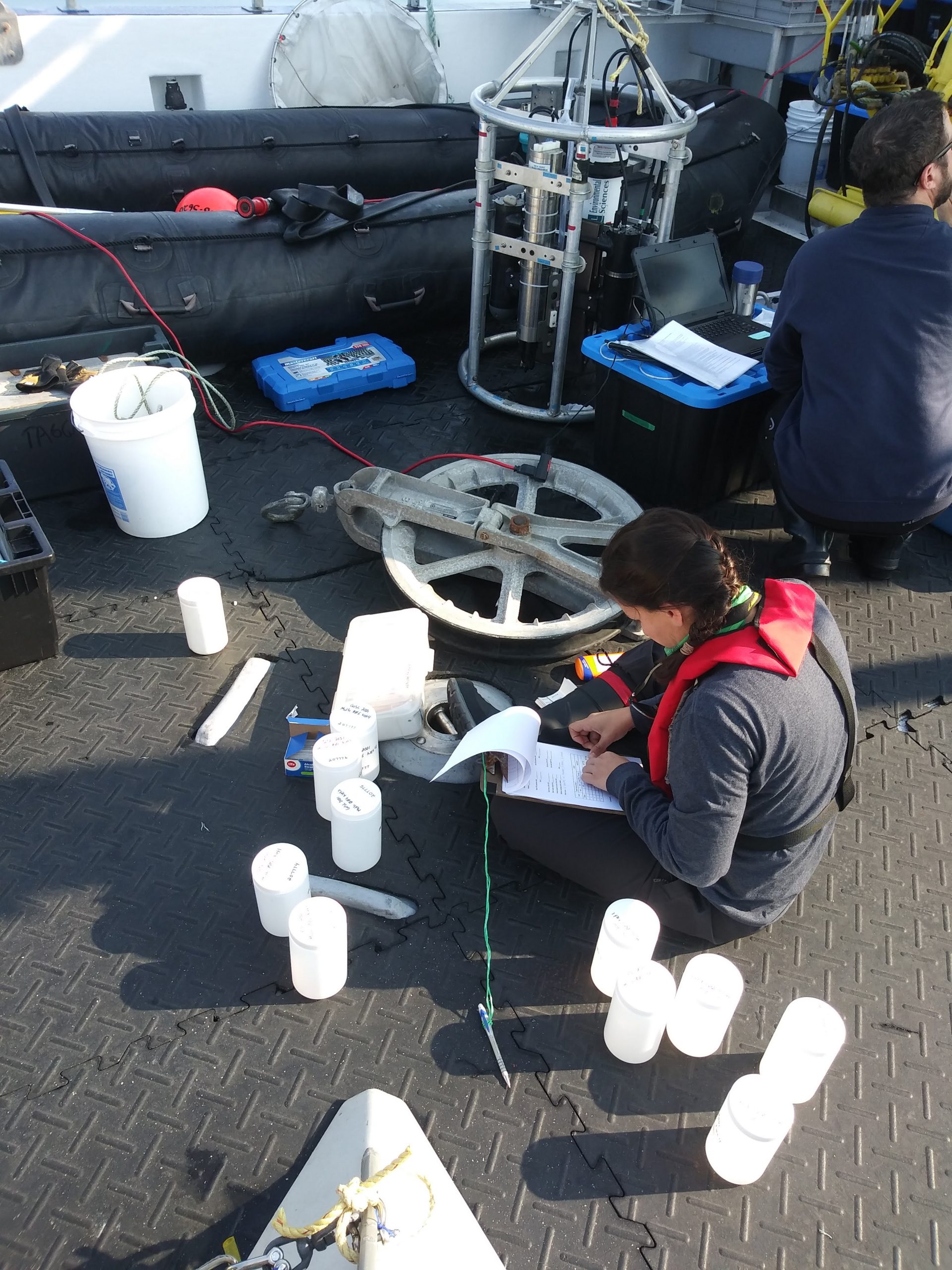

The film crew for Last of the Right Whales came aboard from their charter vessel Marie-Caro for a second day of filming our research team in action. The oceanographic team then led us through a morning of oceanographic sampling, which includes deploying different oceanographic sensors that can quantify plankton in the water column, as well as specialized nets that can collect plankton samples at different depths for species identification.

After the oceanographic sampling was completed, we went “back on survey” and started photographing a large aggregation of right whales. A highlight of the afternoon was documenting two different mom-calf pairs where the calves were testing their independence by keeping a good distance from their respective mothers. We were able to stick around long enough to watch Giza (Catalog #3020) and her calf join back together. As we were waiting for Millipede (#3520) and calf to reunite, we got the call that every right whale biologist dreads: an entangled whale.

The Marie-Caro (documentary charter) was a few miles to the north of our position when they noticed a lot of splashing not too far from their boat. After an initial inspection, it was quite clear that it was a thrashing right whale entangled in fishing gear. They called us over the radio in the late afternoon and all other research activity immediately paused. This became our priority for the rest of the day. As we steamed north towards the Marie-Caro and the entangled whale, tasks got divvied up and a plan began to take shape. When an entangled right whale is discovered in Canada, there is certain protocol that must be followed: the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) and the Marine Animal Response Society (MARS) must be notified and a disentanglement expert is consulted for permission to respond and how to proceed. Safety being a number one priority, it takes a trained expert to assist an entangled whale. Luckily, we had a few on board: Moe Brown is a key member of the Campobello Whale Rescue Team (CWRT) and both captains of the J.D. Martin and the Marie-Caro (Martin Noel and Stephane Ferron, respectively) have both been trained by CWRT for disentanglement.

The location of the entangled whale was just a few miles away, but as emotions rise, time seems to slow. No matter how many entangled whales you’ve seen, it’s doesn’t change the dread of what’s to come, and the fear of whether or not we can help. As we got closer to the thrashing whale, the splashes could be seen from several miles away. When we got close enough, we began to document the whale and the entanglement from cameras on deck and a drone overhead. Through these photos and videos, the details of the situation began to take shape. There were four wraps of rope around the tail stock, rope over the head (from the left side of the mouth over the rostrum), two lines visible along the right side, and there was a trailing line with a buoy. The whale’s peduncle and leading edges of its fluke were scraped raw and bleeding. As the whale violently thrashed about, blood would fly through the air. With blood in the water and the whale clearly in distress, the scene was horrifying. It takes your breath away, seeing any sentient being in so much pain.

I got a short reprieve from watching the horror show play out as I ran below with some photos of the whale to try to match it to a known individual in the North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog. With some help from a flash of cell service and the NEAq team back in Boston, we were able to match the entangled whale to #4615, a 5-year-old male, who did not have a previously known on-going entanglement. This unfortunately was not his first entanglement, but definitely his most severe: he suffered two minor entanglements during his first two years, as evidenced by some scarring on his peduncle. His first few months as a calf were actually quite interesting: he was a part of the now-infamous three-way calf swap during the 2016 calving season. He was first photographed as a newborn calf in mid-December 2015 by the Florida Fish and Wildlife aerial survey team with his birth-mother Harmony (#3115), but by mid-January was seen exclusively with calving female Bocce (#3860), while Harmony seemingly had adopted a calf that had been previous photographed with Cypress (#3440). So while #4615 is genetically related to Harmony, he was raised and weaned by Bocce. There is only one other documented North Atlantic right whale calf swap in the last 40+ years, so this is not a common occurrence.

The whale was thrashing way too much and far too unpredictable for anyone to make any sort of close approach for disentanglement, so we opted to attach a telemetry buoy to the trailing line, so that a highly trained disentanglement team could re-locate #4615 in the near future with a more nimble boat and presumably a more cooperative whale. I checked to make sure that the satellite tag was transmitting properly, then attached it to the telemetry buoy. Shortly afterwards, our first mate Guy Lanteigne had grappled into the trailing line and attached the telemetry buoy successfully. As a seasoned crabber, he is a crack-shot at throwing a grapple. We all cheered, hoping that this buoy would eventually help this poor whale to be disentangled.

Wanting to get as much documentation as possible of the shifting gear on the whale and knowing that a storm was going to move through the area the following day, we stayed with #4615 until dark, which was around 10pm, before heading back to land. He continued to thrash about for the five hours that we were with him, so not only was he bleeding from wounds from the entangling rope, but he was exerting an immense amount of energy towards freeing himself that could have been spent on other activities, such as feeding or mating.

Leaving him out there was hard, but the telemetry buoy made us hopeful. Unfortunately, we found out the following morning that the tag had stopped transmitting around 4:00 a.m. So not only would he be much harder to re-locate, he was now dragging around extra weight. The DFO plane spotted him later that day further to the south and still entangled, but with no telemetry buoy in sight. We believed it to have gotten dragged under the water by the whale, preventing it from pinging a satellite. And that was the last time anyone saw him.

The day after we returned to the dock, we looked through our whale photos from earlier that previous day and at around noon on July 13, we had photographed #4615 not entangled. We had a hunch, based on the whale’s erratic and thrashing behavior, that the entanglement had happened recently, especially since we had been in the area that day and not seen any major splashing until late afternoon. But this confirmed it. We had narrowed the entanglement timeline down to about a four-hour period. This is important data for a couple of reasons: 1. we definitively know where the entanglement occurred, which is often not the case and 2. it gave us another example of how a right whale reacts shortly after being entangled. We only have a few other documented examples of this and are starting to see a pattern of behavior: violent, bloody, and incredibly energy draining.

Exactly three months later in mid-September, the telemetry buoy started pinging again, just north of Prince Edward Island. I was shocked. What did this mean? Was the buoy still attached to #4615? Was #4615 still alive? Unfortunately, the tag stopped pinging again two days later and an aerial survey plane wasn’t able to fly over the area until a few days after the tag went silent. So it remains a mystery for now.

This unanswered question mark of #4615’s fate is a common one for entangled whales. Survey and disentanglement teams try their hardest to do what they can and often put their lives on the line, but there are so many that slip through our fingers or are never sighted to begin with. Even some of the best and quickest disentanglement efforts are not enough to save a life. More than 85% of NARWs have been entangled at least once in their life and that statistic is even more horrifying when you realize how traumatic those events actually are. It is certainly a visual that you can’t un-see and that you carry with you.

We’re extremely grateful to Irving Oil for partnering with us on this critical research since 1998. We are also grateful to Irving Oil and the Island Foundation for allowing us to operate during these financially challenging times. This work would not be possible without their generosity.