Right Whale Population Declines for 10th Straight Year

Scientists say there are just 336 North Atlantic right whales left in the world

By New England Aquarium on Monday, October 25, 2021

By Emily Greenhalgh

Updated March 15, 2022 | Named because they were considered the “right whales to hunt,” the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale population has been in decline since 2010. The species struggles due to impacts from humans. Entanglement in fishing gear, vessel strikes, and the shifting distribution of food sources as a result of climate change plague the whales.

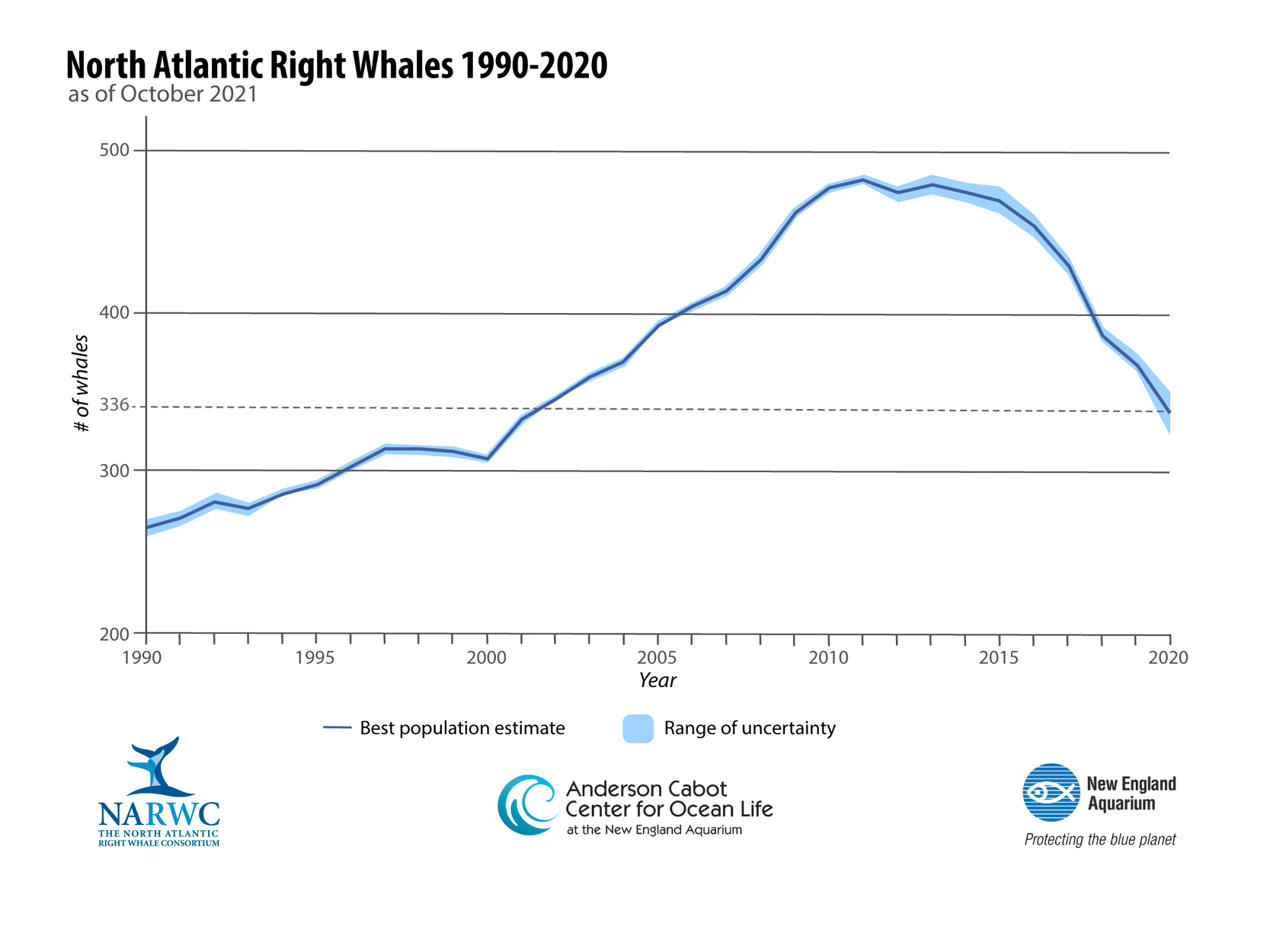

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, the number of North Atlantic right whales slowly bounced back, reaching a high of nearly 500 whales in 2010. But the last decade has been dire for the beleaguered species. The number of whales dropped eight percent from 366 in 2019 to 336 in 2020—the lowest the population numbers have been in nearly 20 years.

“You only have to look at the data to see that the species is in serious trouble,” said Heather Pettis, research scientist at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium and executive administrator of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium (NARWC).

The NARWC releases the right whale population statistics every year at its annual meeting as part of a preliminary Right Whale Report Card. The final report card was released in early 2022 and included no major changes from the preliminary report.

“That precipitous decline is so alarming. We just need to make sure that people don’t toss in the towel on the species because of it,” said Philip Hamilton, senior scientist at the New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life. “They’re a long-lived species and a female can reproduce for at least 40 years. If we stop killing them, their population trajectory can and will reverse.”

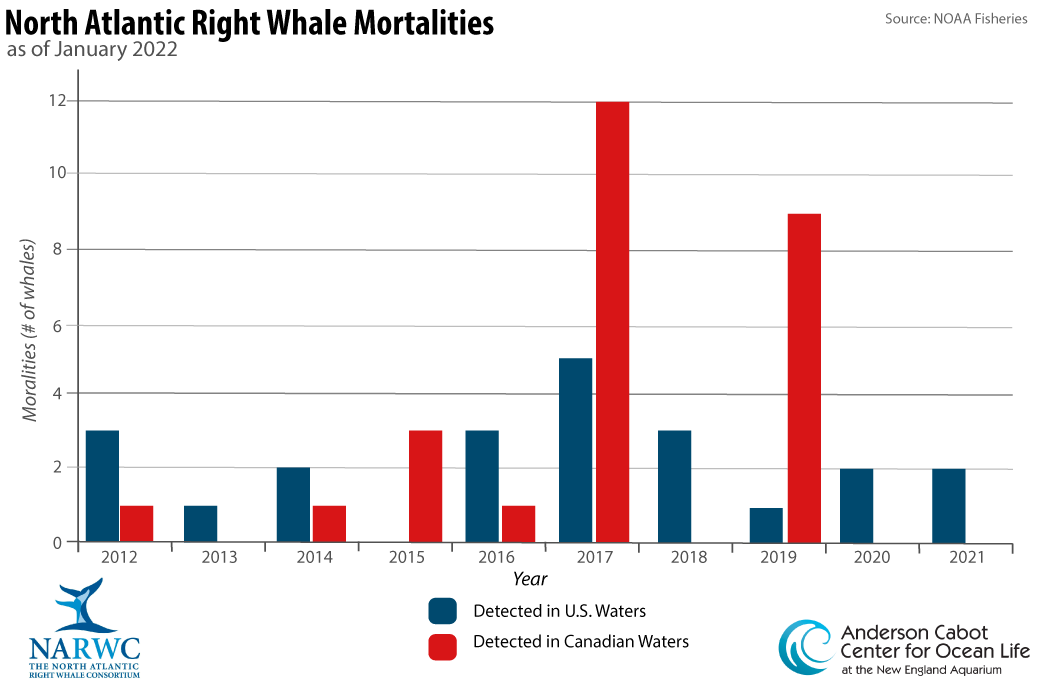

In 2021, scientists observed two right whale deaths, including right whale catalog #3920, an 11-year-old male known as “Cottontail,” who was first spotted entangled in fishing gear off of Nantucket in October 2020 and a stranded right whale calf.

From 2017 to 2021, there have been 34 documented right whale deaths, according to data from NOAA Fisheries, though scientists believe fewer than one in three right whale deaths are observed and believe that number to likely be higher.

As part of the Unusual Mortality Event (UME) that began in 2017, NOAA Fisheries tracks the cause of death for each documented right whale death. Anthropogenic (human-caused) factors, including entanglement in fishing gear and ship strikes, have been implicated in 20 of the 34 most recent deaths. One was a calf who died during the birthing process, and the other 13 had an undetermined cause of death. This is usually because the whale was either not retrieved or was too decomposed to perform a proper necropsy.

A recent publication documented that entanglement or vessel strikes were implicated in all right whale mortalities between 2003 and 2018 for which scientists could determine a cause of death.

“Given that the detected mortalities underrepresent actual mortalities by a significant amount, the state of this species is dire,” said Pettis.

An entangled whale doesn’t die instantly. Instead, entanglements in fishing gear—mostly the heavy ropes and traps of snow crab and lobster gear—reduce the survival probability for whales by exhausting and slowly starving them. Many whales, sometimes with the help of disentanglement teams, manage to shed their gear, but the injuries they sustain can lead to poor health and reduced reproduction well after the initial interaction. Eighty-six percent of right whales have been entangled at least once, according to scientists at the New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life.

Right Whale Calves

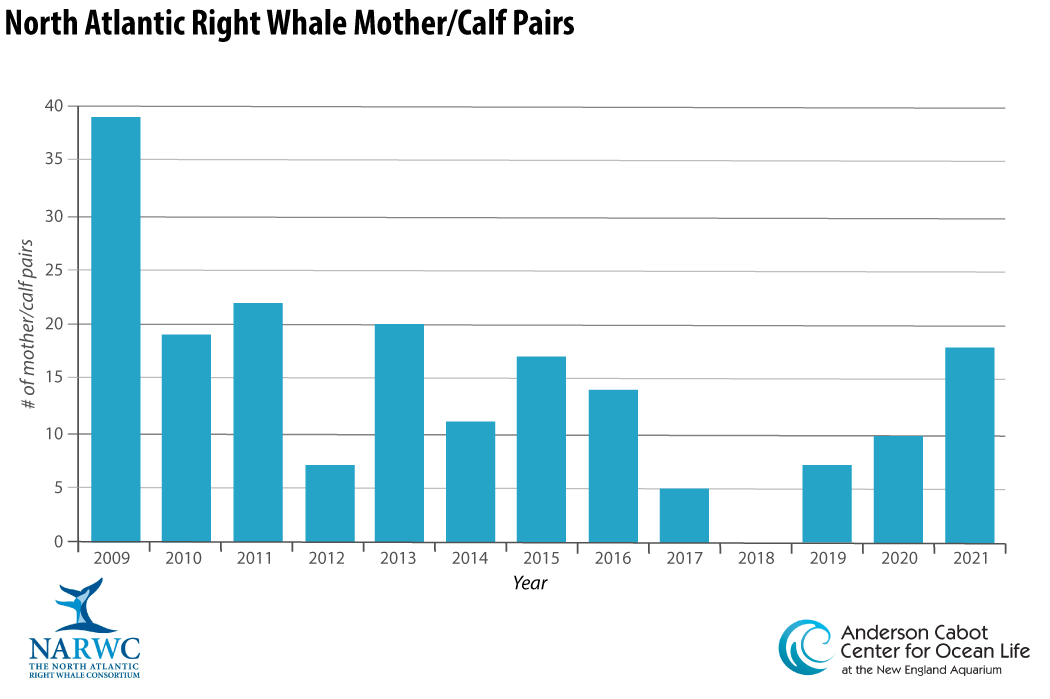

Eighteen mother/calf pairs were detected during the 2020-21 calving season—the highest number since 2013, although one of the 18 calves was hit by a sport fishing vessel and did not survive.

“The combination of fewer detected deaths and an increase in births provides some rare good news for this species,” said Hamilton, but added that scientists estimate that there are fewer than 100 reproductive females remaining.

“Reproductive females” are defined as whales that reproduced at least once and have been seen recently enough that scientists think they are still alive. That number could increase as younger female whales give birth for the first time.

“They definitely can rebound,” said Hamilton. “We just need to stop killing them.”

The North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium

Since 2004, the Right Whale Consortium’s annual report has provided an assessment of where the situation stands for right whales, and, perhaps most importantly, recommendations for the future. This year’s virtual meeting brought together nearly 500 researchers, managers, conservationists, students, and educators from around the world to hear updates on the status of the species. The attendees included scientists from as far away as Australia and New Zealand.

“While there are some challenges to holding a virtual meeting, it really opened it up to more people who wouldn’t otherwise have been able to come,” said Hamilton.

In addition to the 2020 population figure, attendees heard updates about management efforts in both the United States and Canada, new research initiatives, and discussed necessary next steps in moving forward conservation priorities for these whales.

Over the last decade, the distribution of right whales and their habitat use patterns have shifted, likely due to their prey’s movement in response to climate change. Managers in both countries have altered their responses to these distribution changes, but additional modifications are needed to save right whales from extinction.

Learn More About the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium »

The Role of the Anderson Cabot Center

The Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life is a critical component of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium. For nearly 40 years, the Aquarium’s Right Whale Team has been leading research on and advocacy for the species. The team conducts vital work, including cataloging right whales in its extensive photo-identification database, tracking pregnancies and birth rates, investigating fishing gear adaptations to prevent entanglements, working to reroute shipping lanes to prevent deadly vessel strikes, and conducting groundbreaking stress hormone research in whales.