In Puerto Rico, MCAF Project Leader Luis Crespo is Using Cutting-edge Tech to Protect Sea Turtles

By New England Aquarium on Wednesday, June 14, 2023

Lee esta historia en español aquí

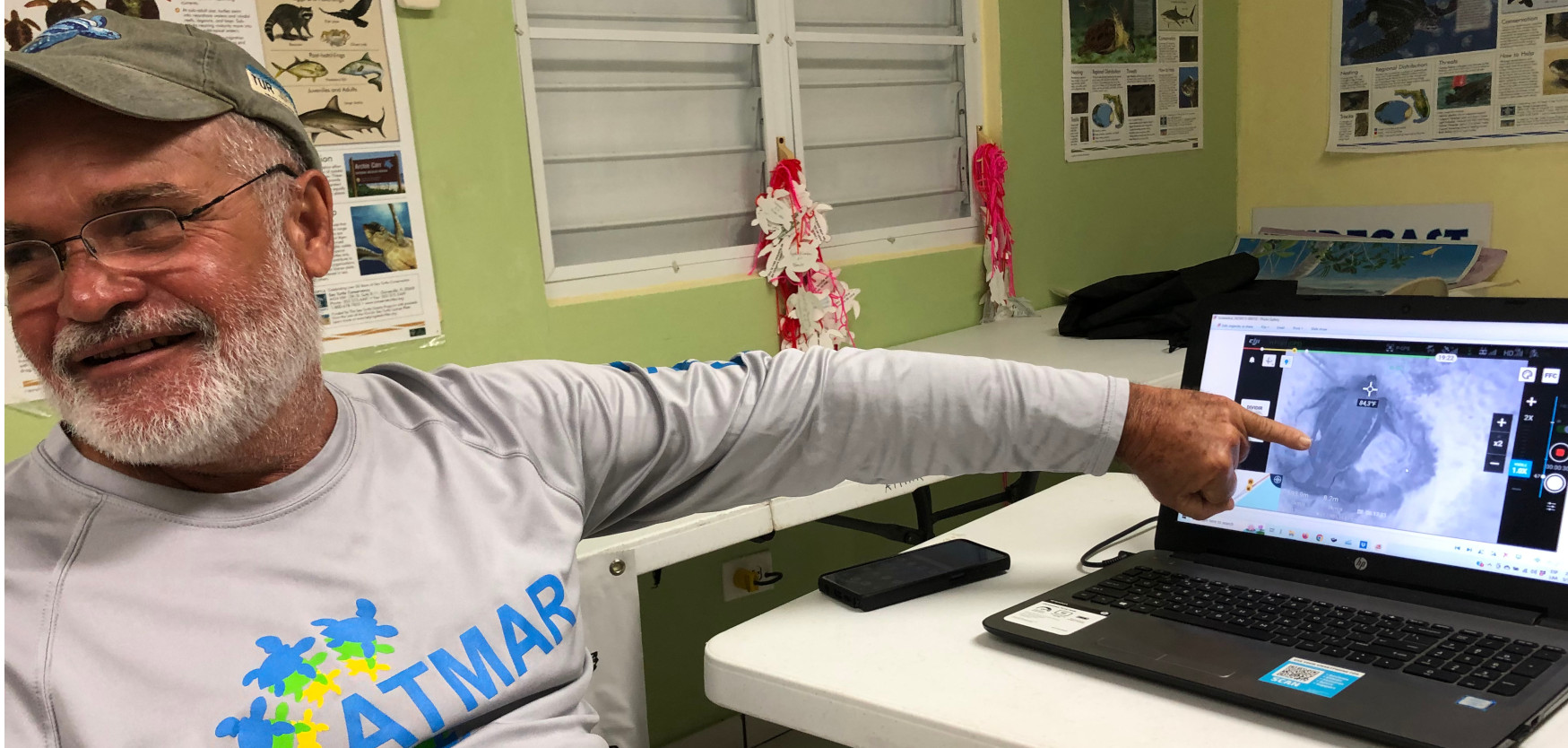

Along the beaches of Maunabo, Puerto Rico, Luis Crespo is on the lookout for endangered leatherback turtles—and doing it in a novel way. Crespo, a recent Marine Conservation Action Fund grantee, is using a drone to spot the turtles from above.

Crespo and his organization, Amigos de las Tortugas Marinas (ATMAR), have been working to identify leatherback and hawksbill sea turtle nesting sites in Puerto Rico for over 20 years. Because leatherbacks nest at night over long stretches of beach, it can be difficult to monitor them. Plus, as nesting sites are often in remote areas, monitoring work can sometimes be dangerous for people on the beaches where encountering predators, such as feral cats or dogs—or even poachers—is a possibility.

Crespo received a grant from the Aquarium’s Marine Conservation Action Fund to acquire the drone for this project. Using the new equipment, Crespo and his team can remotely monitor the two-kilometer beach, which makes spotting the leatherbacks easier, more efficient, and safer for both humans and turtles. He can cover the length of the entire beach with the drone in about ten to fifteen minutes—work that would need to be done hourly on foot or by ATV.

The drone has a thermal camera and a visual camera that can capture high-quality videos both day and night and it can even be used to spot tags on a turtle at an altitude safe enough to avoid disturbing the animal. “The most important thing is that we can see the turtle coming out of the water, or if it is already on the beach, we can detect the stage of the nesting process”, said Crespo. That allows research teams to reach the turtles quickly once sighted.

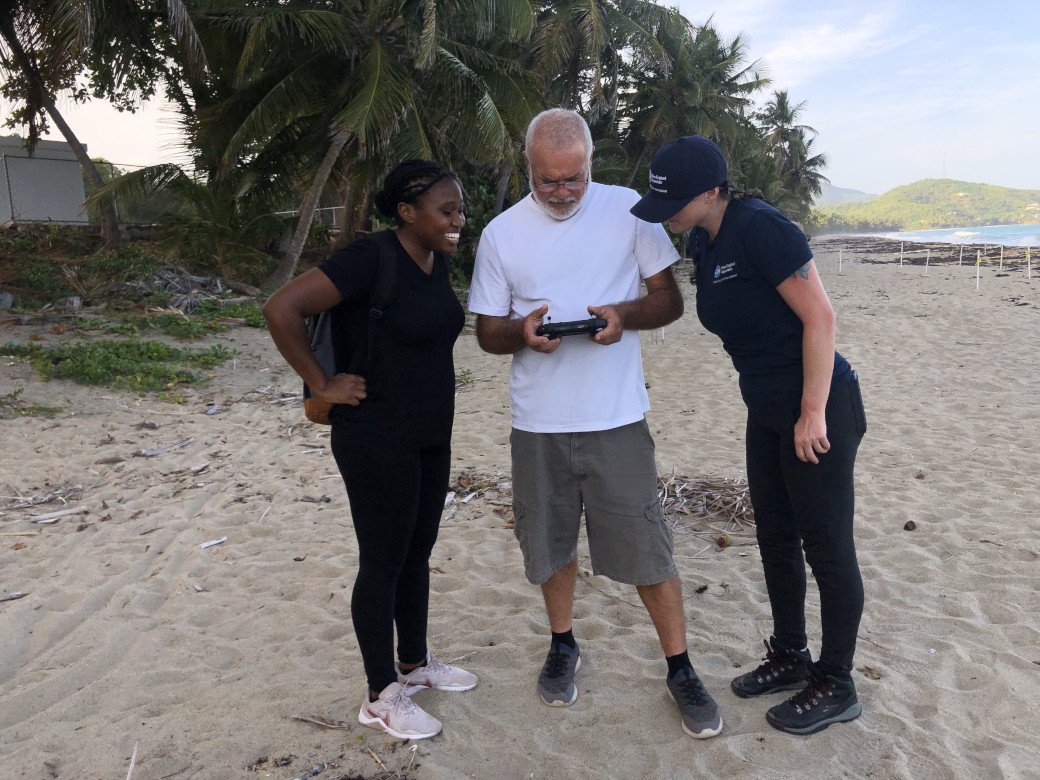

“Timing is everything when it comes to tagging nesting turtles because we only tag them when they’re depositing eggs,” said Aquarium research scientist Dr. Kara Dodge. Dodge, along with Sarah Perez and Alessia Brugnara of the Aquarium’s Sea Turtle Rescue Team, recently traveled to Maunabo to collaborate with ATMAR on leatherback tagging efforts. When a turtle begins nesting, Dodge’s team has a ten-minute window to apply a tag. “If we get there after the turtle has finished laying her eggs, it’s a lost tagging opportunity —so that’s why we were excited to use the drone while we were there,” she said. “It’s so much more efficient at locating the turtles, it feels like a game-changer.”

Dodge began collaborating with Crespo and the team at ATMAR in 2018 after a leatherback turtle she had worked to tag off Cape Cod turned up in Puerto Rico and Crespo found it nesting in Maunabo. Since then, she has traveled to Puerto Rico several times, working with Carlos Diez from the Puerto Rico Department of Natural Environmental Resources (DRNA) and ATMAR to establish the first long-term satellite tagging project for leatherbacks in the southeastern part of the island.

Maunabo is one of several important leatherback nesting sites in Puerto Rico. Before ATMAR began their work, the beaches were a hot spot for poachers who took turtle eggs and harvested nesting turtles. In the decades since, ATMAR has contributed to a near-total reduction in the poaching activity of leatherbacks on the main nesting beaches in Maunabo. Now, ATMAR works to help restore the leatherback population in the Caribbean, including partnering with the Aquarium to study turtles beyond the nesting beach.

“Leatherbacks in Puerto Rico currently have no critical habitat protections. There is almost no data to set those boundaries for coastal waters near important leatherback nesting beaches. The New England Aquarium is working with DRNA and ATMAR to collect this data, which can be used to protect leatherbacks during their critical breeding and nesting period,” said Dodge.

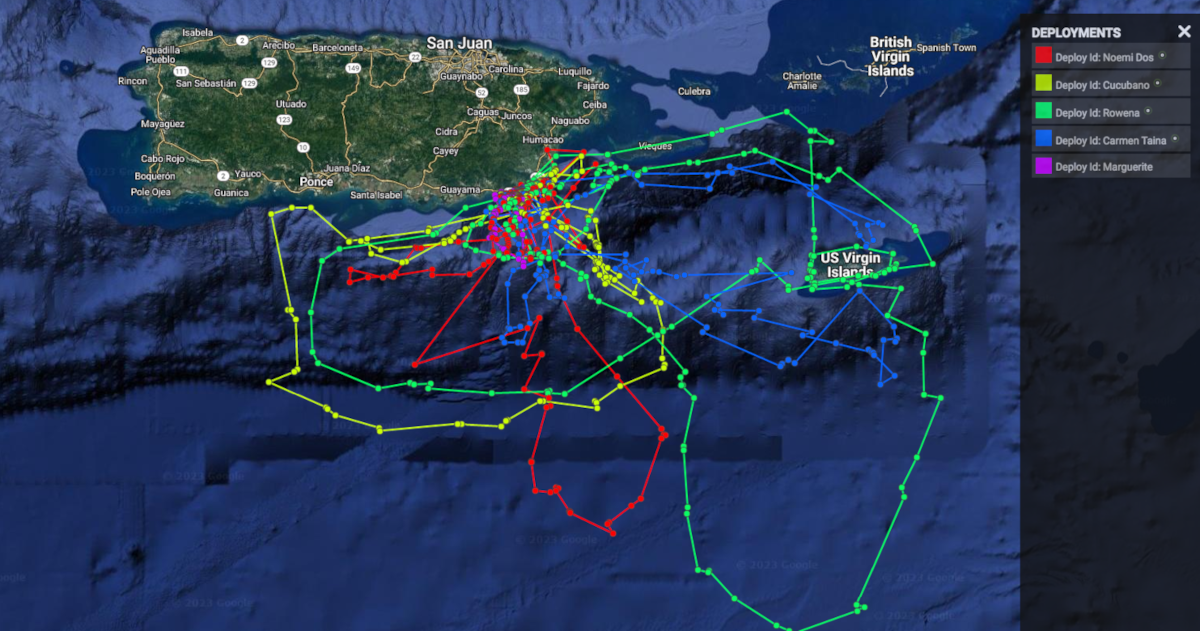

This year, in 2023, the team applied five satellite tags to nesting leatherback turtles on Playa California, including two turtles that had been tagged previously in 2021, providing a rare opportunity to compare data from individual turtles across multiple years. Data transmits daily from the satellite tags, and scientists are hoping to continue tracking the turtles as they begin departing Puerto Rico waters later this month and start heading toward their feeding grounds.

“In Puerto Rico, leatherback migration patterns–where they go when they’re not nesting– is still a mystery for us. We need this information to conduct regional plans to protect them, not only in Puerto Rico but with other countries where we know they transit or feed,” said Diez. “Satellite tags also help us study their nesting movements without nightly beach patrols, which requires costly human effort and resources. From flipper tags, we know that some turtles move between different beaches and don’t always nest on their natal beach. Understanding leatherback nesting dispersal is extremely important because we can use it to determine managements units and which beaches need protection.”

Crespo hopes their efforts in Puerto Rico can help inspire similar conservation efforts in other parts of the world. With leatherback turtle populations in the North Atlantic undergoing widespread nesting beach declines, tagging and monitoring efforts are crucial in helping identify opportunities to protect leatherbacks across the Caribbean.

“I feel like this is the future,” said Dodge. “As drone technology gets less and less expensive, it can become accessible to more people around the globe.”

Crespo agreed. “With the drone, you can be on a very isolated beach, for example, and the only thing you need is more batteries,” he said.

Leatherback research activities in Maunabo are authorized under DRNA Permit #2023-EPE-016