Presenting Thresher Shark Indonesia’s Project at the 2024 NACCB in Vancouver, British Columbia

By New England Aquarium on Thursday, September 05, 2024

This post is one of a series on projects supported by the New England Aquarium’s Marine Conservation Action Fund (MCAF). Through MCAF, the Aquarium supports researchers, conservationists, and grassroots organizations around the world as they work to address the most challenging problems facing the ocean.

By Rafid Shidqi

The weather in Vancouver was very nice the morning I arrived. I had been told that the summer can be pretty damp, with rainfall most likely dominating the daytime hours. But people said I was lucky because that week had been Vancouver’s most sunny and pleasant weather.

I arrived at Vancouver International Airport late at night, along with my wife Addin and our newborn. They accompanied me to the 2024 North American Congress for Conservation Biology (NACCB), which was our first opportunity to travel as a family. There, I presented my research with the support of the Marine Conservation Action Fund (MCAF) at the New England Aquarium.

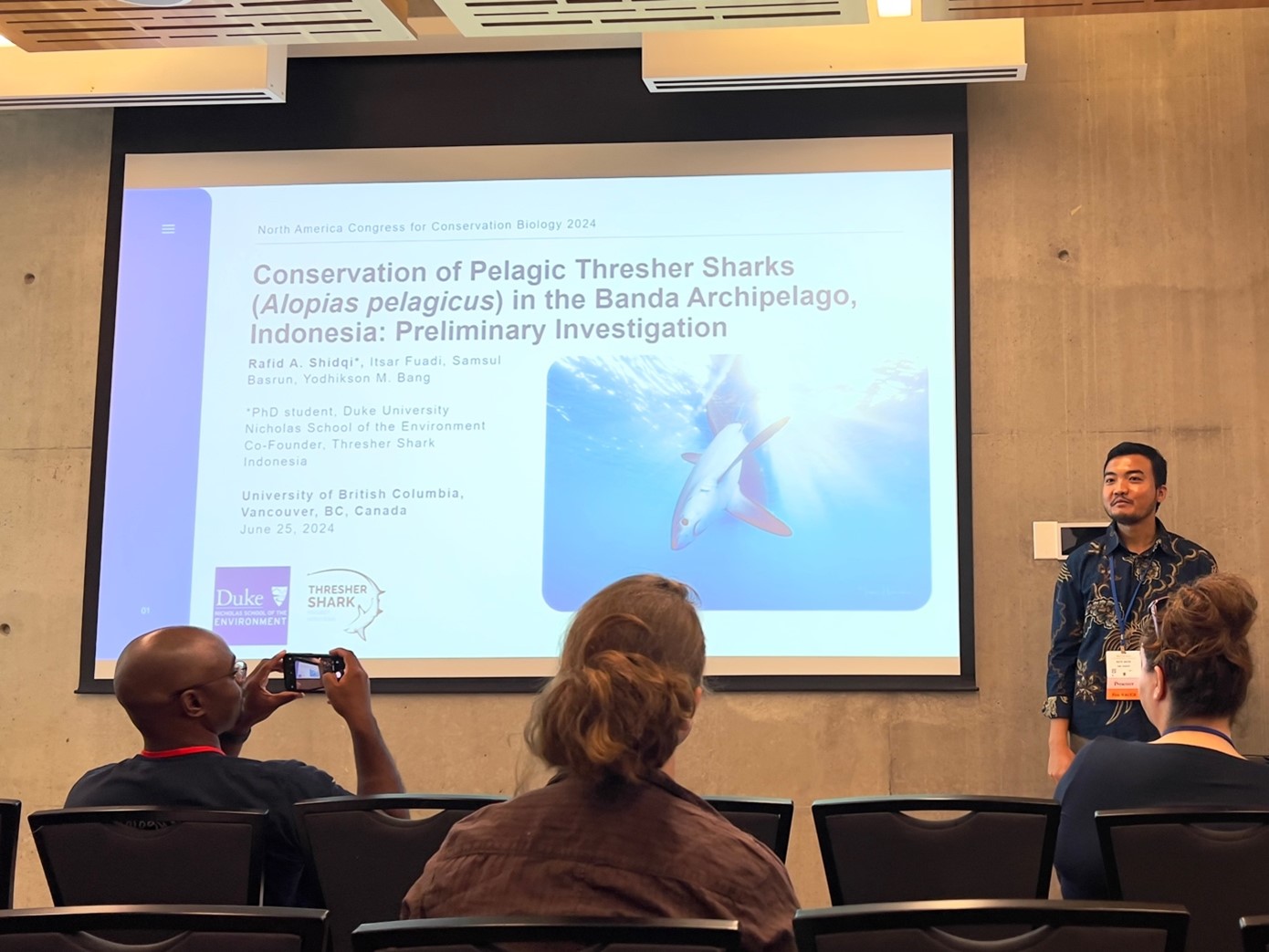

When we reached the venue for NACCB at the University of British Columbia, we saw many people ready to present or learn from others’ conservation research and projects. This event was held for the whole week, with the main symposiums on June 23-28, 2024. I was scheduled for the first seminar slot on Tuesday morning titled “Community-based Conservation and Wildlife Ecology.”

My goal at NACCB was to present our new project in Banda Neira (an island in Indonesia), supported through the MCAF Fellowship that started in early 2023. The project is close to an end, and we’ve discovered many exciting findings on the potential conservation opportunities for thresher sharks in Banda.

The group that I was placed in was very diverse in topics—from dam removal to conservation philosophy to birds—and they presented exciting findings in various regions of North America. I feel outcast at NACCB since the event was initially organized to share lessons among conservation academics and practitioners across North America, most in the United States or Canada. But I guess since I’m attending Duke University for my PhD, I can still feel a bit relevant, though the work I presented took place very far away in the Southern Hemisphere.

One of the interesting talks that still sticks with me was a presentation by Alison Ormsby about “Adventure Scientists,” a citizen scientist platform that engages outdoor enthusiasts in contributing various data and information about natural systems. The platform makes the data widely available to scientists, conservation managers, and governments. This citizen science platform collects data such as microplastics in the ocean and tree leaves across the United States national forests, among others. Alison shared that the data they’ve collected aided the government in deterring illegal logging in one of the US forests because DNA allowed them to trace where the logs were harvested. It is so cool to learn about real examples of how data could inform policy and enforce laws in conservation.

On the second day, I was invited by the Society for Conservation Biology (SCB), North America Education Committee, to a session titled “Celebrating Diversity in Conservation Teaching.” This session was a separate forum where they invited various educators and practitioners in conservation to share lessons, challenges, and innovation to inspire each other.

I was asked to share our work, “Thresher Shark Conservation Champion,” a project we initiated in 2020 to train Alor Island’s brightest and most promising Indigenous leaders to be future marine conservationists. The Champion project was very successful and has trained 36 young indigenous leaders of Alor. Many Champion alumni have gone on to various fields and careers after graduating, such as continuing their master’s education via government scholarship, being the youngest nominee of Village leader, working in government sectors, or being in a national army. Though not all focused on conservation careers, we’re humbled to see how they grow and use their environmental and leadership knowledge in these various pursuits.

The “Celebrating Diversity in Conservation Teaching” session was very meaningful. I initially thought that practitioners in North America would dominate it and that I would again be the only non-North American person in the room. But wow! I’ve heard and learned from folks who are also coming from Southeast Asia, like a lecturer from Nottingham University in Malaysia, who is developing conservation games to be implemented in schools and education programs in Costa Rica.

While going through the session, I learned a common thread about being conservation practitioners that I feel is not only relevant to the situation in Indonesia/Southeast Asia. I met Sydney Collins, the founder of Women in Seabird Science based in Newfoundland, who presented her successes and challenges in leading the initiative. What I found very striking was that issues related to conservation struggles are universally valid across regions. According to Sydney, her inspiration to start the initiative was because women were so underrepresented, and difficult to find a role model who succeeded in navigating careers as bird scientists and conservationists. She said the platform has inspired many young women, not only in North America but globally, to pursue higher education in this sector.

However, though very inspiring, the story is very common that many conservationists struggle to make ends meet, are burdened by excessive expectations regarding funding, and have to work without pay.

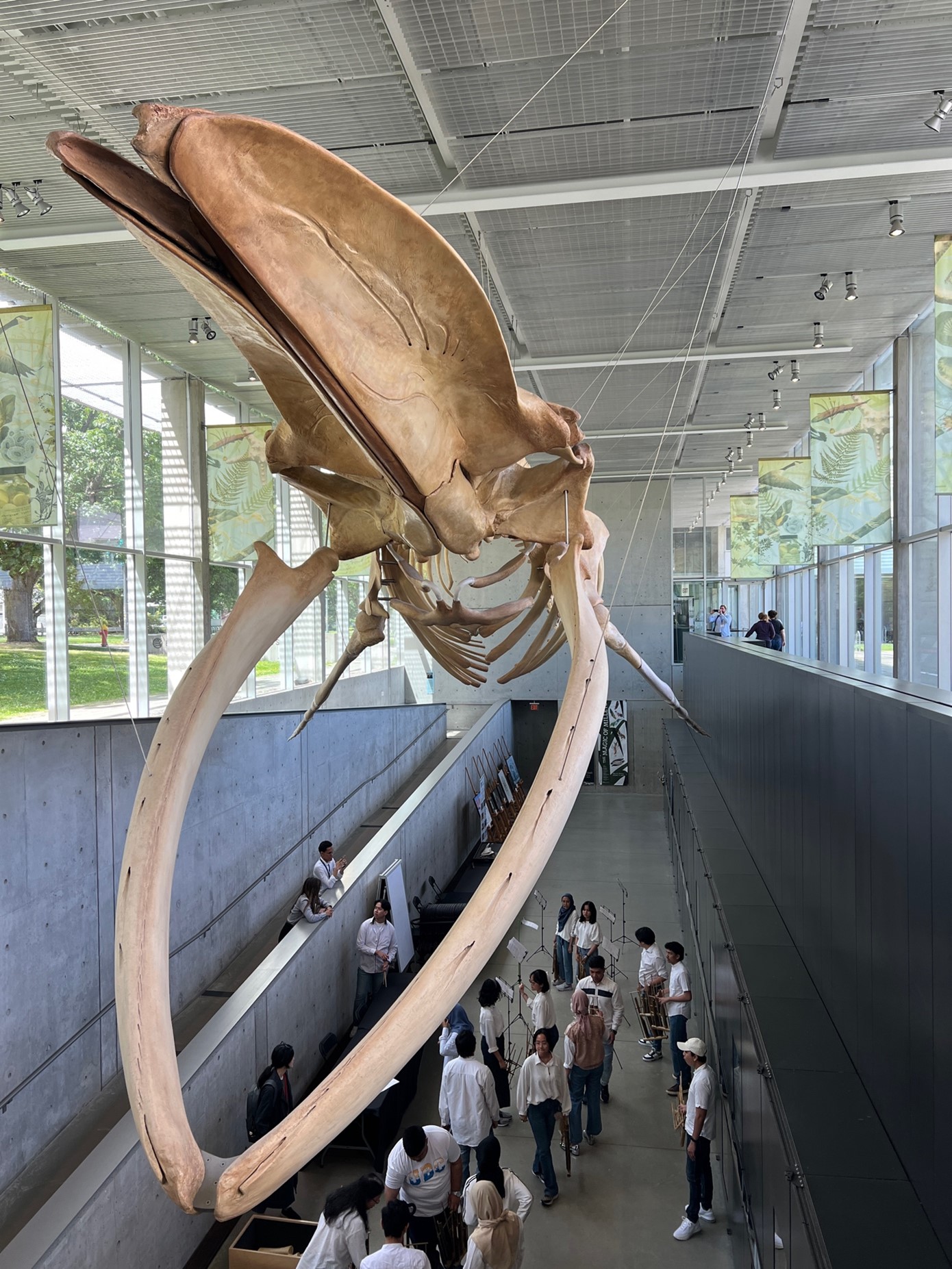

Another highlight of the conference was the presence of Indonesian art and culture, which was led by University of British Columbia’s Professor Agni Klintuni, who happens to be an Indonesian professor! Seeing the traditional Angklung performance at the Beaty Conservation Museum and Indonesian undergraduate and graduate students playing some familiar Indonesian national songs was refreshing. Hearing them speak the Indonesian language and talking to one of them makes me miss home a lot!

Lastly, a very important highlight was the last session with the IISAAK Olam Foundation, which shared indigenous-led conservation initiatives in Canada. It was heartwarming and humbling to hear from three panellists fighting to revive Indigenous cultures and rights in British Columbia, including restoring Indigenous practices to achieve food resilience in this increasingly capitalized world.

This word and wisdom will stick and most resonate with me:

“We must see ourselves as part of the natural system to do meaningful conservation. We were born in this world very vulnerable, and we humans are part of the ecosystem in which we need water, food, and shelter to survive and live. We must ‘connect’ with these indigenous values because no matter where we are from, we are eventually created from the soil and, thus, part of the land.” – Dawn Morrison, Founder/Curator of Research and Relationships, Working Group on Indigenous Food Sovereignty