Construction Update: As we enhance the look and feel of the Aquarium and make structural improvements to the penguin exhibit, some exhibits are temporarily closed, and the penguins are off exhibit until February 13. Learn more.

The Trust Family Foundation Shark and Ray Touch Tank will be closed from January 5 to January 6.

MCAF Fellow Lucy Keith Diagne: Saving African Manatees

By New England Aquarium on Saturday, April 16, 2022

By Jacquinn Sinclair

Long ago, Dr. Lucy Keith-Diagne, a Marine Conservation Action Fund fellow and executive director of the African Aquatic Conservation Fund, knew she wanted to study manatees. Diagne, who grew up in New Jersey, learned about them in school and later went home to tell her parents about her discovery. Since then, the experienced cetacean biologist has studied many other animals, including seals, turtles, and penguins. But it’s the manatee—a large, elongated animal with flippers and a paddle-shaped tail—she’s focused on.

Manatees, which descended from a land animal ancestor that might have resembled a dog-sized hippo according to Daryl Domning’s findings, Diagne says, are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the act prohibits the hunting, capturing, and killing of all marine animals. The West Indian manatee, Trichechus manatus, includes two distinct subspecies, the Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) and the Antillean manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus). Adult manatees are roughly nine feet long and can weigh in at 1,000 pounds. They reproduce every two to five years, and their calves can weigh in around 40-60 pounds.

The Florida manatee is what most people are familiar with, but Keith-Diagne studies the African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis)—which lives in remote, murky waters—from her post in Senegal. Recently, the New England Aquarium had a chance to talk to Keith-Diagne about her research, the challenges manatees face, and how we can best protect them.

NEAq: What are some of the threats manatees face?

Lucy Keith-Diagne: Fisheries bycatch, illegal hunting, dams, both entrapment behind dams and crushing in dam structures, and habitat destruction. As people develop or overutilize coastal habitats, that’s a problem for manatees.

NEAq: I read that the manatees you’re studying are smaller in size than their Florida cousins. In what other ways do they differ?

Keith-Diagne: It’s not really smaller as much as thinner. In Florida, the winters are cold, and they have to stay chubby to survive it, but we never get cold weather in any part of their range in Africa. So, they don’t need to be bulky. Here, they’re more streamlined and tubular. I’ve heard them described as torpedo-shaped. That’s one defining characteristic. In some places, they are a bit smaller lengthwise than Florida manatees. The main thing people notice that’s different about them is their eyes protrude more, and they look bug-eyed compared to a Florida manatee. They also have some skull or cranial morphology differences. That means there are some skull characteristics we can define the species by scientifically. For example, if someone handed me a manatee skull from Florida versus Africa, I could tell the difference. Most people couldn’t.

NEAq: I read you were documenting the food resources manatees consume and the habitats they live in. Can you talk a little bit about it?

Keith-Diagne: First, let’s talk about habitat. Everybody thinks of manatees in Florida and Crystal River. In Africa, they have a wide range of different habitats. They can live in near-shore coastal systems like mangroves or seagrass beds, but they also live thousands of miles up rivers. They live in equatorial central African rain forests. When those rivers overflow during the rainy season, they swim among the trees and eat the same fruits elephants eat in the dry season. They live in the northern part of the range in Senegal, where I am, in the Sahel at the edge of the Sahara. And so, the rivers are shallow except during flood season.

So, they’re eating incredibly different foods in all of these places. They can eat everything from seagrass to fruits from forests that fall into rivers. They eat fish, mussels, and clams, which is different from any other manatee species. Although the Florida manatee has been documented sometimes taking fish in the Florida Keys, it’s rare and not a standard food item. So, here, they have a varied diet. So far, we’ve documented over 90 different species of plants that African manatees eat, and I still think there are plenty more and many species of fish.

NEAq: That’s fascinating. Let’s talk more about you. How did you decide you wanted to research this particular marine animal? What drew you to the manatee?

Keith-Diagne: I think my interest in them is partly because they’re so adaptable to where they live. They’re animals that can adapt to living among humans if we just give them enough space and care. I also think [they’re interesting because they] live in mostly muddy water environments, yet they can navigate over and over to their favorite spots every year. Well, how do they do that? They’re certainly not seeing their way there. Nobody knows how they are sensing [their way] through dark rivers and waterways hundreds of miles of distance. In Florida, that’s critical because if they don’t get to their warm water site, they will freeze to death.

NEAq: Well, talk to me about their vision since you said they’re certainly not seeing their way there. Also, earlier, you mentioned the African manatee has bulging eyes. Does that mean their vision is possibly better than the Florida manatee?

Keith-Diagne: We don’t know. One thing we can say about African manatees is we mostly don’t know much. They’re the least studied of all the species. And that’s for several reasons. One, because they live in this enormous 21-country-range and they live in a lot of very remote places. Also, there hasn’t been the kind of steady research funding for people to study them throughout Africa. So, I guess my point about vision is inferred chiefly from Florida manatees, where their vision has been studied.

But maybe their bulging eyes give them some other part of their vision. We don’t understand yet, and we don’t know. But, if you think about muddy and tannic brown waterways, where they mostly live in Africa, it’s dark and murky; they can’t depend on sight alone. They have to rely on other things like hearing and the hairs on their bodies. All manatees, not just our manatees, are sensory organisms, and they can detect things like current changes with the hairs on their body, just like a lateral line on a fish. So that’s probably a critical sense to them because they can feel their way around and through the water.

NEAq: In addition to the work you’re doing, how can we, the public, best protect them?

Keith-Diagne: In Africa, we realized poverty is a huge driver for hunting. So, I have to convince people what the manatee’s benefit is to humans to get them to protect them. One of the benefits we can say for sure is that manatee feces—since they eat a lot of plants—are a food source for juvenile fish in many of the systems where they live. So, it’s not unusual to see groups of fish around manatees. So, the point we try to make with different communities is: if you protect manatees, you help encourage baby fish, which people value for food. So, we’re trying to get people to understand: everything is connected.

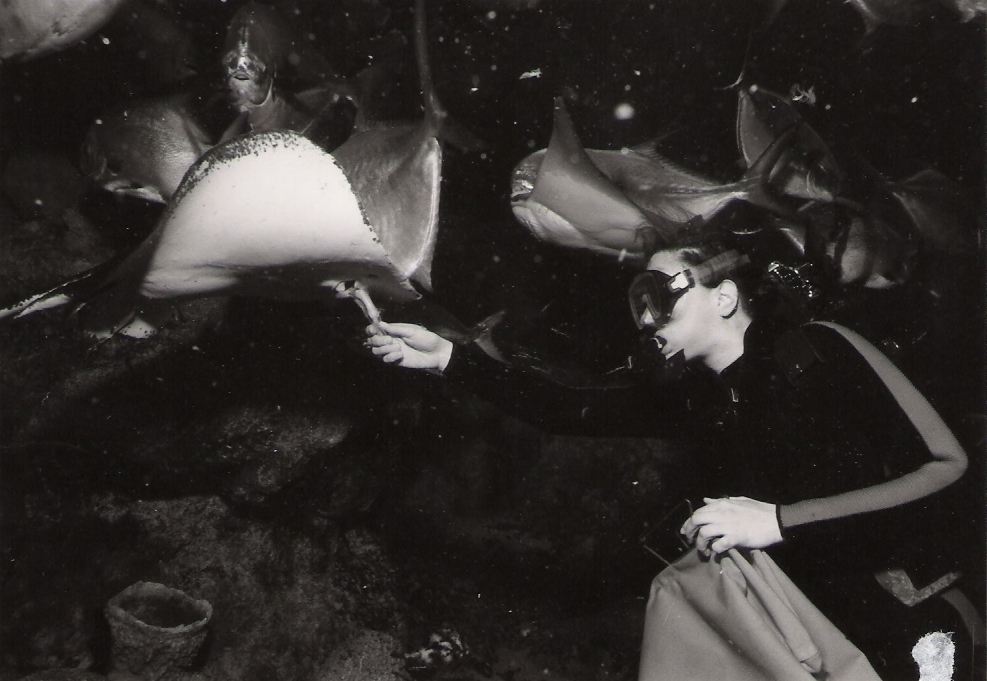

Watch MCAF Fellow Lucy Diagne’s Virtual Manteee Visit on Facebook