Lucky Catch

How decades of fisheries catch data helped us learn about common thresher shark distribution and movements in the northwest Atlantic Ocean

By Jeff Kneebone, PhD on Thursday, January 07, 2021

This is the second of a series of blog posts about collaborative common thresher shark research being led by the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium. Here we present the final results of a study that was introduced by a previous blog post, found at this link: https://www.neaq.org/investigating-common-thresher-sharks-in-the-north-atlantic/

If you’re a fan of sharks, watch Shark Week, follow social media, and read scientific blogs (including our past posts on sand tiger, sandbar, blacktip, and nurse sharks) you are probably well aware of how scientists use various types of tags to study the distribution and movements of sharks around the world. While tags surely provide incredible information about where individual species exist in the vast ocean, there is also much to learn from data collected by other activities, like fishing. For example, information on when, where, and how fishermen catch sharks and other fish species over time – referred to as fisheries-dependent data – can be just as valuable for examining distribution and movement patterns and identifying areas in the ocean that are important for fish species.

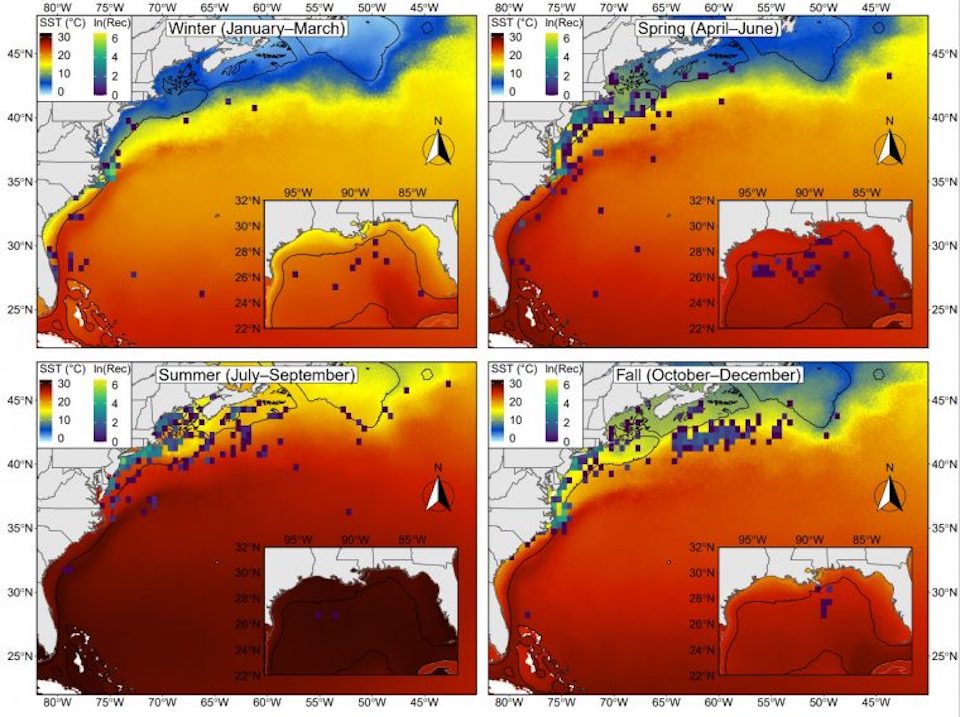

Using fisheries-dependent data collected by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada and various groups from the National Marine Fisheries Service from 1964 to 2019, our research team mapped the distribution of common thresher sharks (Alopias vulpinus) by season, sex, and life stage in the northwest Atlantic Ocean. These maps illuminated brand new information about the occurrence of common thresher sharks in coastal and offshore waters from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada, and demonstrated how the species shifts its distribution throughout the course of the year. As you can see from the set of maps below, common thresher shark distribution seems to be linked with ocean temperature, with the sharks generally being found further north in the warm summer months and further south –and sometimes offshore- during the colder winter months.

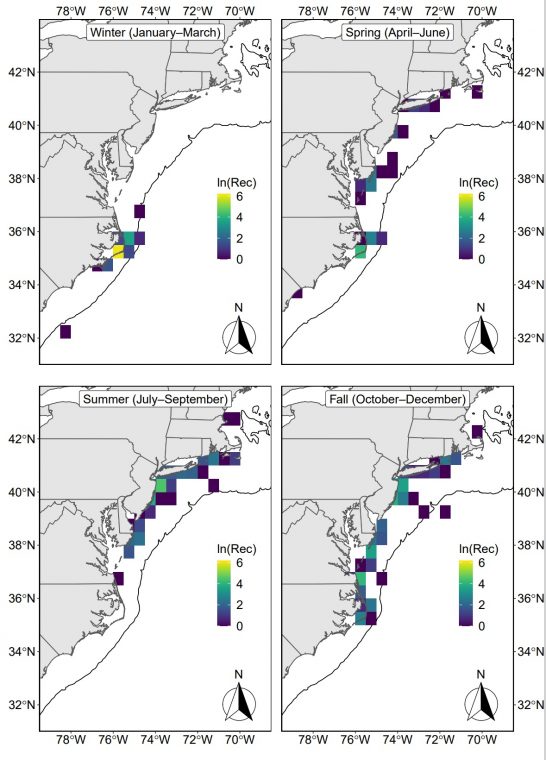

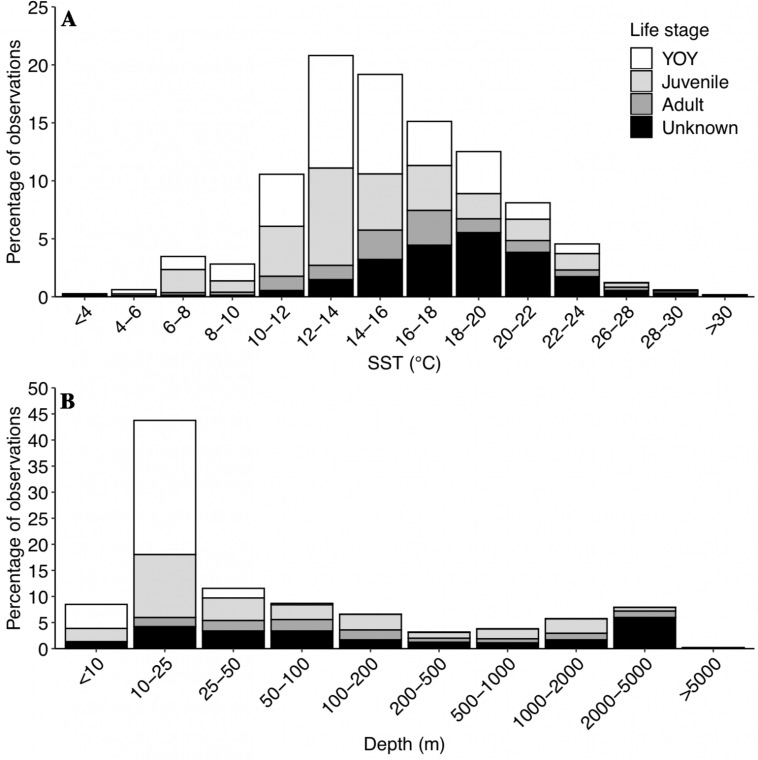

Of particular interest, the maps revealed that common thresher sharks less than one-year-old (young-of-the-year) don’t move as much as juveniles or adults and prefer to remain in shallow, nearshore waters less than 50 meters (150 feet) in depth throughout the year. You can see from the maps below how these young sharks were caught primarily near the coast. You can also see how they preferred northern waters in the summer months and retreated to warmer southern waters in the winter, moving between them in the spring and fall.

Data on sea surface temperature and water depth at the time of capture also indicated that the species is found in water temperatures from 4 to 31 °C (39 to 88 °F) – but prefers 12 to 18 °C (54 to 64 °F) and is primarily caught in waters of less than 200 meters (600 feet) deep.

Collectively, the results of this study will help to identify essential fish habitat for each life stage of common thresher sharks along the U.S east coast and to develop future management measures for the western North Atlantic region. The fisheries-dependent data we’ve compiled will also soon be combined with the tagging data that our group has been collecting on common thresher sharks over the past five years to improve our understanding of how this species uses the Atlantic Ocean and how it may be influenced by climate change.

You can read more about this research in a recently-published scientific paper available at the following link:

https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf-content/fish-bull/kneebone.pdf

This research was supported by NOAA’s Saltonstall-Kennedy Grant Program.

Research team:

- Jeff Kneebone (New England Aquarium, Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life)

- Heather Bowlby (Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada)

- Joe Mello (Northeast Fisheries Science Center)

- Cami McCandless, Lisa Natanson, Nancy Kohler (National Marine Fisheries Service, Apex Predators Program)

- Brian Gervelis (National Marine Fisheries Service Cooperative Research Branch, Integrated Statistics)

- Gregory Skomal (Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, Massachusetts Shark Research Program)

- Diego Bernal (University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Department of Biology)