Local Sharks: Tagging Sand Tiger Sharks in Boston Harbor

This is one of a series of posts by Associate Scientist Jeff Kneebone, Ph.D., about his work with juvenile sand tiger sharks. This post highlights recent tagging efforts in Boston Harbor.

By Jeff Kneebone, PhD on Friday, December 15, 2017

Historically, sand tigers were one of the most abundant shark species found in New England coastal waters. Unfortunately, sustained fishing pressure in this region, and elsewhere throughout their northwest Atlantic range, resulted in the decline of their population along the U.S. East Coast by an estimated 70 to 90 percent from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. As a consequence of this decline, sand tigers became rare throughout New England, even in areas where they were once prolific.

Fortunately, thanks to proactive fishery management and conservation policy at the state and federal levels, this species has undergone a resurgence in New England coastal waters during the past 15 years. Sand tiger sharks are even showing up regularly in a region in which they were once scarce: north of Cape Cod. Take a look at a previous post in this series to learn more about the historical context of sand tiger sharks along the New England coast.

One area where this resurgence of sand tiger activity has been reported is Boston Harbor (Dorchester Bay, Hingham Bay, Broad Sound, Nahant Bay, and Quincy Bay)—literally right in the New England Aquarium’s backyard! Given the amount of human activity and potentially harmful disturbance that exists in this busy, metropolitan area—such as bottom dredging and boat traffic—it is important for us to understand how sand tigers use this area in both space and time and to determine if they may be at risk from these human activities.

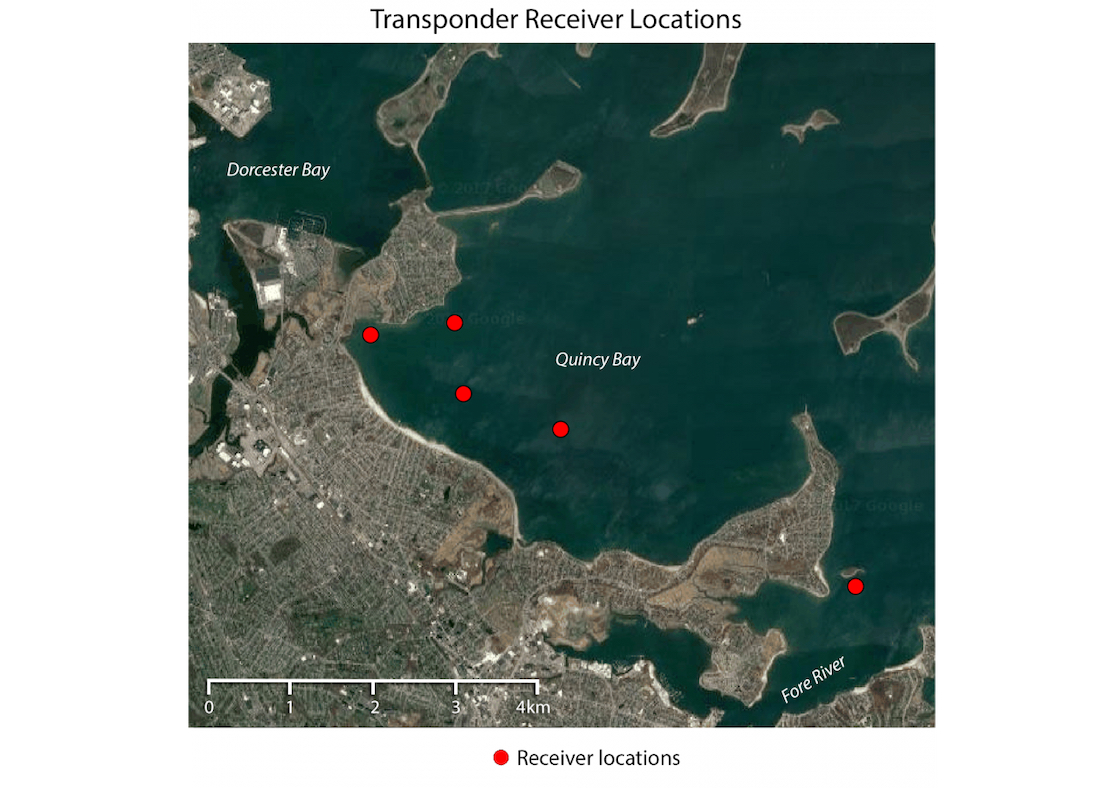

During summer 2016, we began a tagging study in collaboration with the Massachusetts Shark Research Program that uses passive acoustic telemetry—a method that can be likened to an E-ZPass® system for sharks—to monitor the presence and movements of sand tigers in Boston Harbor. In late July, we were lucky enough to tag one, small female shark that we monitored within Quincy Bay for several weeks.

This preliminary success prompted us to increase our efforts to learn about sand tigers in Boston Harbor during this past summer. Specifically, this year we were interested in exploring how many sand tigers may be in this area, how much time they are spending here, and what areas of the harbor they are using.

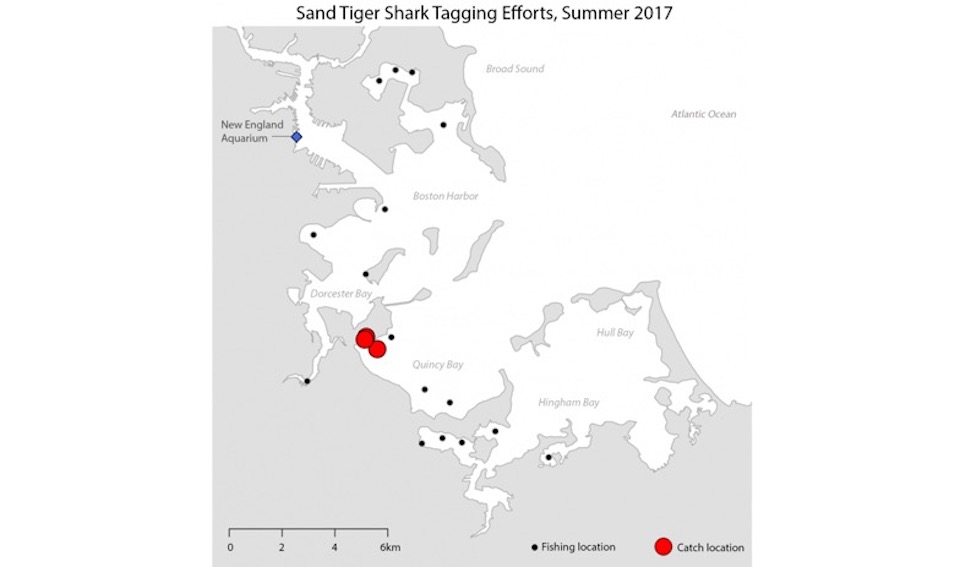

In late July 2017, we resumed our investigations and quickly tagged three sand tigers (two females and one male) with acoustic transmitters over the course of two days within Quincy Bay—the exact same area that we tagged the shark in 2016!

As expected based on our past experiences, all of these individuals were juveniles ranging in size from about 4 to 5 feet; however, one individual was the largest sand tiger that has ever been tagged by our group in Massachusetts waters! Over the next week, we continued to focus our efforts in this bay, but unfortunately we were not able to tag any additional animals.

Moving onto new grounds within the Boston Harbor system, we stayed on the hunt for sand tigers over the next two months. Unfortunately, despite great efforts, we encountered no additional sharks in any other location.

While our inability to tag additional specimens was disappointing, when we looked at the movements of the sharks that we tagged in Quincy Bay, we started to understand why we had so much trouble finding sharks in other areas. Just like the shark that we tagged in 2016, all three of the sharks that we tagged this July stayed in Quincy Bay throughout the entire summer! Not only did they stay in Quincy Bay, but they each spent up to 70 percent of their time in one small corner of the bay, near the entrance to a small creek, often being present in very close proximity to one another.

Come late September—as if they were on a schedule—all three sharks left Quincy Bay within four days of one another, presumably to commence their southward fall migration. With any luck, we’ll be able to track the whereabouts of these sharks during their migration through our participation in the Atlantic Cooperative Telemetry Network and hope that they come back and visit us in Boston next summer!

Sand Tiger Shark Research in Boston Harbor

Acoustic telemetry technology is helping Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life researchers track the movements of sand tiger sharks in Quincy Bay within Boston Harbor. The blue bar on the right corresponds to the tide stage. The higher the bar, the higher the tide. Watch the bar to see how the sharks move with the tide.

Despite the small number of individuals that we encountered in Boston Harbor, the extreme site fidelity that multiple individuals exhibited to Quincy Bay suggests that this area is of particular importance to juvenile sand tigers. With more acoustic transmitters and acoustic receivers already in hand, we intend to continue our investigation of juvenile sand tiger presence in this bay during summer 2018, and to further expand our search for other sand tiger hangouts throughout the greater Boston region.

For more information on sand tiger sharks, check out the other posts in this series:

- Local Sharks: Studying Sand Tiger Sharks

- Local Sharks: Using Technology to Study Sand Tigers

- Local Sharks: The Importance of Shark Tagging

Investigators: Dr. Jeff Kneebone, Dr. John Mandelman (Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life) Connor White, Dr. Greg Skomal (Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries)