Identifying Soon-to-be Right Whale Moms

Scientists hope to spot a new mother and calf pair after detecting pregnancy hormones in a North Atlantic right whale

By New England Aquarium on Friday, December 17, 2021

By Katie Graham and Liz Burgess

It is an exciting time of year for our Right Whale Research Team: it’s calving season! Each winter, a portion of the North Atlantic right whale population migrates to coastal waters off Florida and Georgia. These traveling whales are primarily pregnant females, who head to the warmer waters to give birth. With less than 350 individuals remaining, each birth represents hope for the continuation of the species.

During calving season, teams from Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute, Florida Wildlife Research Institute, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, and others conduct surveys throughout this important habitat to look for prospective moms, identify those who successfully give birth, and register new calves. This information is shared in real-time with our Right Whale Research Team at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium who track the life history events and health information on individuals in the population via the Right Whale Catalog.

Do we know which right whales are expecting to be moms?

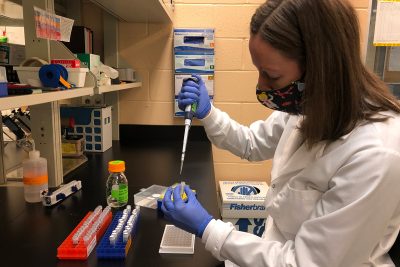

Cue the Anderson Cabot Center’s Wildlife and Ocean Health Program. Although many of our right whale biologists conduct research on the water via boats and planes, a small crew of us work “behind the scenes” in a laboratory on the top floor of the Aquarium. For over 20 years, scientists in the Wildlife and Ocean Health Program have studied the health and hormones of North Atlantic right whales using lab-based techniques—including developing the first-ever pregnancy test for a swimming whale!

Hormones are powerful chemical messengers that control biological processes including reproduction, metabolism, and stress responses in animals (including humans). By studying reproductive hormones using specialized lab tests called assays, we can learn about events such as the onset of sexual maturity, cycles of reproductive activity, and perhaps, most excitingly, pregnancy.

Testing for progesterone and why it’s important

Finding this result is not as straightforward as it sounds—it comes from our incredible collaborative network and a rather unexpected place: a single plop of poop (Yes, poop! Or, more scientifically known as feces or scat). What is considered “waste” by many is in fact an invaluable scientific tool, as it contains remnants of many biological compounds including hormones. These poop samples make their way to our lab thanks to the dedicated efforts of our boat-based field teams who can spot this bright orange floating feces while out at sea (pictured at right).

Finding this result is not as straightforward as it sounds—it comes from our incredible collaborative network and a rather unexpected place: a single plop of poop (Yes, poop! Or, more scientifically known as feces or scat). What is considered “waste” by many is in fact an invaluable scientific tool, as it contains remnants of many biological compounds including hormones. These poop samples make their way to our lab thanks to the dedicated efforts of our boat-based field teams who can spot this bright orange floating feces while out at sea (pictured at right).

Summer field work leads to an exciting discovery about Koala

This summer, our field team surveying the Gulf of Saint Lawrence in Canada happened to be in just the right location to see North Atlantic right whale Koala leave behind this unknowingly critical sample and the team successfully scooped it up for later analysis.

In recent weeks, some thrilling news came out of our lab: North Atlantic right whale “Koala” (Catalog #3940) may be pregnant! When testing for a hormone called progesterone, we found Koala had extremely high levels of this hormone. This is a sign of pregnancy in right whales, as well as in many other mammals, with the amount of progesterone often being hundreds of times higher in pregnant females compared to those that are not pregnant.

Koala’s pregnancy is particularly exciting, as this will be her first calf! At 13 years old, her journey to motherhood is starting a bit later (right whale females can give birth starting around age 8-9 years old). With fewer than 100 reproductive female right whales remaining, new mothers and every new calf represent the future of the species. Koala, the 2009 calf of Cypress (#3440) has one younger sister #4640. Since 2015, Koala has been a frequent visitor to the relatively newly used feeding area in the Gulf of St. Lawrence where her poop sample was collected.

Koala’s pregnancy is particularly exciting, as this will be her first calf! At 13 years old, her journey to motherhood is starting a bit later (right whale females can give birth starting around age 8-9 years old). With fewer than 100 reproductive female right whales remaining, new mothers and every new calf represent the future of the species. Koala, the 2009 calf of Cypress (#3440) has one younger sister #4640. Since 2015, Koala has been a frequent visitor to the relatively newly used feeding area in the Gulf of St. Lawrence where her poop sample was collected.

Thus far, Koala has not been observed by aerial teams in the southeast, but it is still relatively early on in calving season. We are hopeful she will soon appear with a calf by her side. Alternatively, a few right whale moms do not give birth in the monitored southeast region, and Koala could surprise us by giving birth in a less watched habitat. Whether she is spotted over the coming months on the calving ground or seen later in northern feeding areas, we certainly look forward to the next time Koala is sighted.

Having a pregnancy test for right whales is important for helping to understand the challenges faced by this critically endangered species, which includes reduced reproduction. Discovering that a right whale is pregnant provides the first step to determining whether females are getting pregnant and then losing the pregnancy, or if they are not getting pregnant at all. So, we all guardedly await news of a successful birth and healthy calf.

It’s amazing that this single, unassuming fecal sample collected over the summer provides such an exciting peek into Koala’s story and gives us hope for another addition to the North Atlantic right whale population.

Check the New England Aquarium’s 2021-22 North Atlantic right whale calving season blog to see if Koala’s been spotted as the season progresses.