How We Work With Animal Poop to Protect the Blue Planet

By New England Aquarium on Friday, April 05, 2024

Here at the Aquarium, whether it’s our Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life right whale researchers or one of our Animal Care team members, we’re always working to protect the blue planet. But it might just surprise you that part of that work involves a whole lot of animal poop!

That’s right—poop plays a big role in our conservation research, animal health care, and day-to-day activities. Here, learn from a few people around the organization about the ways we work with animal poop and how that helps make a difference for the ocean and marine life.

We collect it

For our right whale team, poop is one of the biological samples that our researchers collect during fieldwork. “We don’t see poop as often as some may think,” said Assistant Research Scientist Amy Warren. “While whales are constantly eating and likely pooping a lot … it [often] dissipates by the time we get the boat to the area. So, it’s always a good day when we manage to get our gloved hands on a sample.”

Right whale poop has a distinctive brown-orange color and—luckily for our researchers—floats at the surface of the water. If the team is able to spot (or, occasionally, smell!) right whale poop, they work quickly to scoop it up with a specialized net attached to a long pole. The net and sample are then placed in the “poop bucket,” where the sample can be transferred to individual containers for processing and study.

“We have lots of whale poop, lots of manatee poop, and an almost infinite amount of northern fur seal samples,” said Danielle Dillion, an associate scientist and lab manager in our Wildlife and Ocean Health program. There’s so much poop because it just happens to be one of the easiest biological samples to collect in the field and you don’t have to bother the animal in the process.

“You can’t just go up to a large whale and take a blood sample,” Danielle said. “So you go out and find a whale that’s pooping.”

That’s what Research Scientist Dr. Liz Burgess did in the field in the Bahamas in a study of beaked whales. Instead of collecting the sample at the surface, Liz swam behind a group of whales, keeping her eyes peeled for an individual that was pooping. Once she spotted it, she collected the sample in a net—“like cleaning a fish tank,” Danielle said—and prepared it to be shipped back to the lab in Boston.

Our aquarists will also collect poop samples from various animals in our care so that the samples can be used to better understand the animals’ health. At our Quincy Animal Care Center, where Senior Aquarist Kristen Ulrich and team care for animals in quarantine before they’re transferred to or from the Aquarium, that can mean collecting poop once a week for three to four weeks to screen for parasites. Those samples are collected from the water and placed into a small container for analysis by our Animal Health team. Because the team takes care of many species of fish, that also means handling many types of poop. “Fun fact: Sharks and rays have a spiral colon, which sometimes leads to spiral-shaped poop!” Kristen said.

Lindsay Phenix, a senior aquarist for our Giant Ocean Tank (GOT), is also collecting poop samples from rays as part of a “rainy day” collaboration with our Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life. The GOT has a mixed population of rays, with four cownose rays and one southern stingray, and the 24 samples aren’t specific to any one animal. “We’re interested in possibly learning more about the overall health of our stingray population,” Lindsay said. “We specifically timed our sampling to align with ‘quiet’ or stable times within the GOT and collected during times of possible stress—which included the introduction of our nurse shark.”

We study it

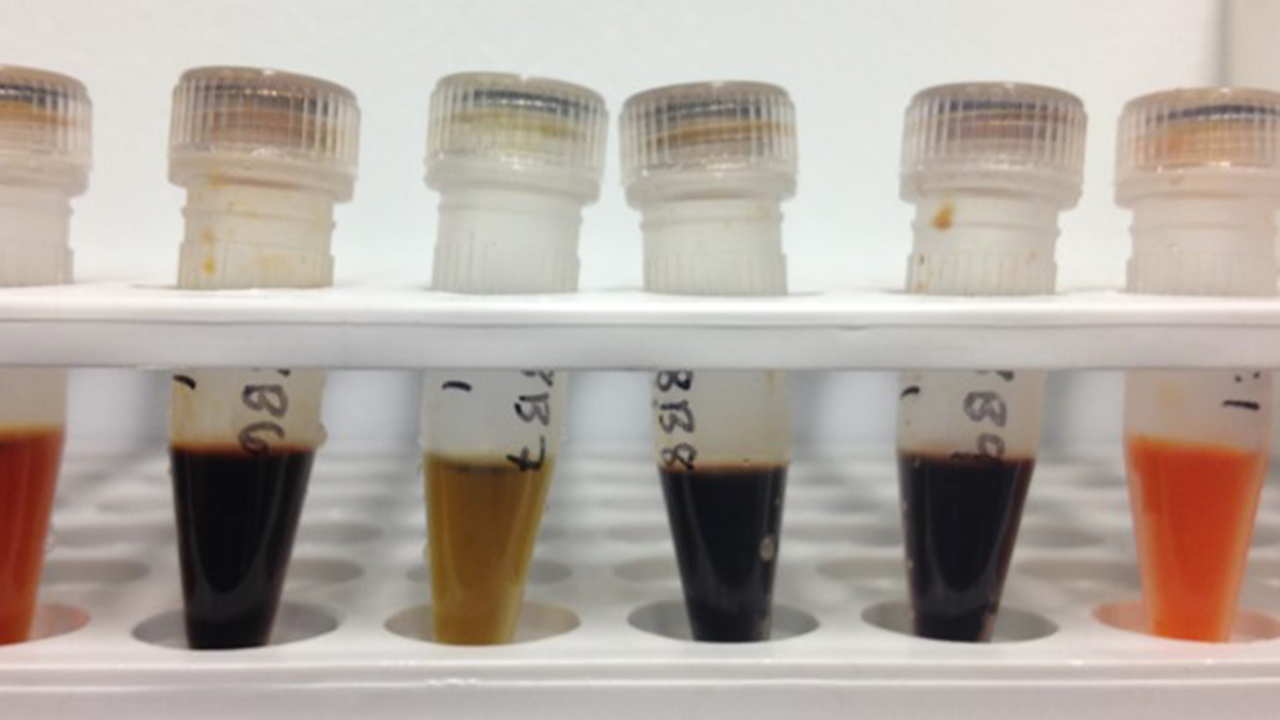

Poop—or more formally, “fecal samples”—is one of the many biological samples Danielle and team study to learn more about the health of different species. Blubber, plasma, shark mucus, whale blow, and baleen are also part of the collection.

Danielle works to analyze some of the right whale poop samples from the field—as well as samples from other marine animals, too. While the team studies an array of biomarkers from the different samples they collect, using poop to analyze an animal’s hormones can tell researchers a lot about that animal.

“It can help us answer questions about individuals and populations,” Danielle said. “Progesterone and testosterone can help us answer questions about reproduction and pregnancy. Hormones like corticosterone and cortisol help us assess response to stressors, and we look at things like thyroid hormones to assess growth and metabolism.”

Right whale poop samples are also shared with other institutions across the US and Canada for research into everything from right whales’ diets to their digestive health. “Understanding what is happening on an individual level can provide insight into the overall health and trajectory of the population, which is very important in our mission to better protect North Atlantic right whales,” Amy said.

We use it to monitor animal health

In our Animal Health Department, fecal exams are just one of the many ways we monitor animal health. According to Hospital Manager Nina Nahvi, animals that are in quarantine will be monitored for parasites; poop samples can also be used to diagnose or monitor a sick animal, or a fecal exam can be opportunistic—just to check in on an animal’s overall well-being. “If a stingray poops while we do an exam, we’ll collect and test it to be thorough,” Nina said.

We clean it up

Of course, a big part of regular care for our animals means cleaning up after them—and that includes their poop. At the Quincy Animal Care Center, Kristen says the time they spend cleaning depends on the type of system and the animals living in the tank. “In quarantine systems, we clean daily to prevent any parasites from breaking out. But in larger tanks, like the ones that hold the sharks and rays, those get vacuumed one to two times a week depending on the number of animals in there.”

At the Aquarium, in the majority of our exhibits, a robust water filtration and monitoring system helps keep things clean. But some animals, like our African penguins, need a little extra help from their human caretakers. Penguins poop on land an average of seven to eight times per hour—multiplied by 38 African penguins, and it’s easy to see how that adds up quickly. On any given day, there are up to six people cleaning the exhibit, and sprinklers go off four times per day to assist in the process. Despite how often we clean it up, all that penguin poop—which is called “guano”—doesn’t pose any health concerns for the birds. “They would actually dig their nests in it in their natural environments!” said Senior Penguin Trainer Amanda Barr.

Thanks to poop—and science!—we can learn a lot about marine animals both in our care and in the wild and use that knowledge to better protect the ocean.