How Do Sharks Mate?

The answer comes from the world's longest-running shark behavioral study. For the past 25 years, shark scientists have visited Dry Tortugas National Park in Florida, the only place in the world where shark mating behaviors can be predictably observed in the wild.

By Nick Whitney, PhD on Thursday, August 02, 2018

How do sharks mate? That’s probably a question you’ve never asked yourself, but it has an interesting answer. They don’t spawn like many other fish species, which release their gametes into the water column to meet up and create fertilized eggs and larvae. No, sharks have internal fertilization. Just like mammals, an adult male and female shark have to physically come together so that the male can pass his genetic material into the female’s body where her eggs will be fertilized.

For those of you familiar with mammalian mating habits, you may be wondering how sharks manage to accomplish such a complicated physical maneuver in an aquatic environment without the benefits of gravity, hands (did you know that sharks don’t have hands!?), and other tools and techniques often used by land animals. It’s not easy, but the short answer is that it involves a lot of biting, thrashing, and rolling.

How do we know this? Most shark species have NEVER been observed mating in the wild. It’s probably a pretty rare event in their lives (females of many shark species only reproduce once every two to three years, though they likely mate several times per mating season). Usually mating takes place in deep or murky waters where humans are unlikely to see it. Occasionally a lucky diver will catch a glimpse of shark courtship or mating behavior in clear water and capture a still photo or a few seconds of video that some desperate scientist (like yours truly) will analyze to death and publish in a scientific paper.

Other than those serendipitous events, the majority of what we know about shark mating behavior comes from a single population of nurse sharks (Ginglymostoma cirratum) in the Dry Tortugas National Park (DRTO), Florida. This small cluster of islands, 70 miles west of Key West and only accessible by boat or seaplane, has been an annual shark mating ground for well over a century!

I just spent the end of June and beginning of July in DRTO with Theo and Wes Pratt (longtime shark scientist at NOAA), who are now in their 26th consecutive year of studying this population of mating nurse sharks.

What makes this study so special? Several things:

- This is the only place in the world where sharks can be observed mating in clear, shallow water on a predictable basis (every summer) and thus provides a reliable site for studying this rare, but crucial, behavior.

- This is the longest running shark behavioral study in the world. The Pratts, with occasional help from myself and Dr. Jeff Carrier (Albion College Professor Emeritus and cofounder of the study), have kept the study going every year for 25 years, and have observed many of the same adult sharks (identified from external and internal tags, as well as fin markings) for over 22 years.

- We know these animals’ histories going back two decades: what years they were here, with whom they mated, what years they likely gave birth, and – for many – where they spend their time the rest of the year.

- The majority of what is known about shark courtship and mating behavior comes from this study at this location—because it is the only place in the world where these behaviors can be observed on a predictable basis.

- Because sharks are so distracted by courtship and mating activities, we scientists can approach them in the water extremely closely without the use of chum, bait, or cages. This area thus provides a rare glimpse of natural shark behavior in the wild, up close and personal.

- Research by the team has directly led to the seasonal closure of the shark courtship and mating grounds to boating and other human recreational activities. This is the only marine protected area in the world designated to protect a shark mating ground.

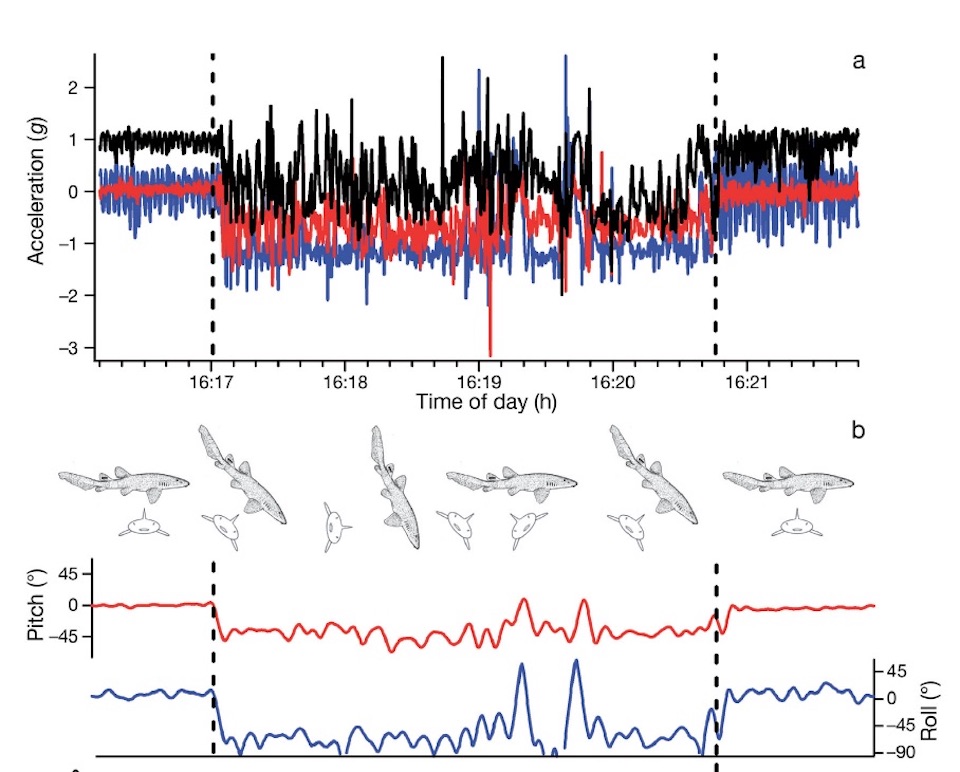

While most of the work in this study has come from direct observation and video analysis of the animals in the shallows during daylight hours, in recent years we have been able to collect longer, more detailed behavioral records even at night and in deep water. We’ve been able to do this by using some fancy data-logging tags called accelerometers (you probably have one of these sensors in your hand or on your wrist right now) to document the behavior of these animals every second for days at a time. Remember the thrashing and rolling that I mentioned above when sharks mate? It turns out that that kind of behavior shows up very clearly in accelerometer tag data, which makes these tags a great tool for studying shark mating. Understanding when, where, and how sharks mate helps us understand what places and times are most important for species survival, and can also help explain their long-term migrations and habitat use.

In addition to conducting the annual shark census and recording as much natural behavior as possible, the agenda for this year’s trip was to test some new tags and new attachment techniques.

I spent several weeks in the lab before the trip madly re-designing and 3D-printing tag attachment components, having fin clamps made and modified, and working with colleague Connor White on several new floats and other gadgets he was creating for testing on the sharks. After a couple of all-nighters and some travel hiccups along the way, I arrived in DRTO feeling like I needed a nap!

Luckily paddling a kayak over the top of crystal clear tropical waters with nine foot sharks swimming below you is a great way to get the blood (and adrenaline!) flowing, and by the time I arrived shark mating season was in full swing.

This is the first in a series of blogs about my Dry Tortugas trip. Follow along for more updates on this expedition, including technology #FAILS, close encounters with non-nurse sharks, and how I accidentally tagged a turtle on shark expedition.