Construction Update: As we enhance the look and feel of the Aquarium and make structural improvements to the penguin exhibit, some exhibits are temporarily closed, and the penguins are off exhibit until February 13. Learn more.

How Aquariums Contribute to Shark Research and Conservation

By Nick Whitney, PhD on Friday, July 12, 2024

It’s Shark Week and the New England Aquarium is bustling with shark activity—not the made-for-TV kind but the actual conservation science and education work that helps to better manage shark fisheries and inspire the next generation of scientists and ocean lovers.

For starters, scientists in our Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life are in the full swing of field season. We’re catching and tagging sandbar sharks off Nantucket, porbeagle sharks in offshore New England, spinner and bull sharks in Florida, blue and mako sharks in the New England offshore wind lease areas, and we will soon be tagging sand tiger sharks in Boston Harbor as well. Three of us are giving talks at the American Elasmobranch (sharks and rays) Society meeting in Pittsburgh, PA, this week, and a couple of us are co-authors on a newly published paper about drone observations of basking shark courtship in Cape Cod Bay (say what now? You can read the paper here).

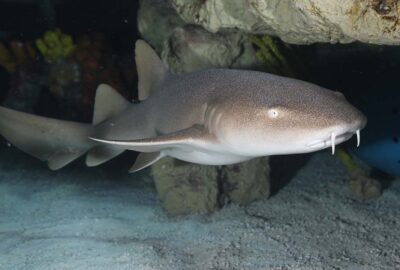

On top of all that, several of us just returned from the Dry Tortugas, Florida, where we spent the last half of June observing, capturing, and tagging nurse sharks in the 33rd year of our study on this population in a unique shark mating ground and aggregation site.

There are a lot of things that are unique about this study and location, and one of those things is the collaborative approach we’ve adopted in recent years to maximize our expertise and impact. For the last three years, the scientists leading this study have been fortunate enough to have colleagues from the Animal Care team at the New England Aquarium in the field working alongside us.

Animal Care staff are the highly trained team members who keep the Aquarium’s animals healthy and thriving, but we’re learning that they’re also incredibly valuable people to have in the field. Not only are they dedicated, passionate, and hard-working (all pre-requisites for surviving long days of grueling fieldwork), but they also bring a new perspective and fresh set of skills to our decades-long study. In the last three years, Animal Care team members have helped us improve the grid system we use to mark the study site, update our data sheets to make them more functional, and raise the standards of our field surgery tools and techniques.

So far, we have had six different Animal Care staff join us in the field in Dry Tortugas, and their experience with us has also given them a new perspective on some of the animals under their care. One colleague, Lindsay Phenix, has now joined us in the field for three consecutive years and has become such a nurse shark expert that she was recently selected as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) Studbook Keeper for Nurse Sharks.

“Wow, AMAZING title,” you say, “but what is it?” In this role, Lindsay will be leading the charge to compile and maintain the demographic history of all 139 nurse sharks across 45 AZA institutions, to inform population management decisions related to this species.

We’re incredibly proud to have Lindsay in this role, and the significance of it carries extra weight for me. In 2001, as a new graduate student at the University of Hawaii, I was in desperate need of genetic samples from whitetip reef sharks. My search led me to board a plane from Honolulu in the aftermath of 9/11 (my flight had about ten people onboard and we were escorted by fighter jets out of Hawaiian airspace) to attend the first Elasmobranch Husbandry Conference in Orlando, Florida. Whitetip reef sharks are found in aquariums all over the world, so I figured attending an international meeting full of people who cared for them would be a great way to build my sample collection quickly. There was just one problem: the people who cared for the animals were often unable to verify the exact origin of their sharks! Some were collected in the wild but without a definite location, others were born in aquariums but the precise lineage was a mystery. Overall, my trip produced just a handful of samples from two locations where I could verify the sharks’ geographic origin.

That was over twenty years ago and aquarium industry standards have improved substantially since then, in part thanks to the AZA Studbook Keepers program. So, for Lindsay to take on this role for nurse sharks (my—and now everyone’s—favorite shark species) is a really exciting moment for the Aquarium with special meaning for me. Great work, Lindsay!

Our collaborative approach to this long-term study of nurse sharks in the wild is one way that aquariums can have a major impact on shark research and conservation. Our study site is now a marine protected area (MPA) during the shark mating season, but being an MPA cannot protect it from the effects of climate change. It has recently been severely impacted by Hurricane Ian in 2022 and subsequent storms, and our long-term dataset is more valuable than ever to understand how the sharks’ use of the site will change going forward. Long-term studies like this cannot be supported with typical grants that expect a project to be completed in a 12-24 month period. It takes institutions, like the New England Aquarium, to step up and support this work in order to understand the impacts of climate change and chart a path forward for the health of our oceans.