Please note: We strongly recommend purchasing tickets in advance to guarantee entry, as we do sell out during school vacation week (April 19 – 27).

Highlights from This Year’s North Atlantic Right Whale Summer Fieldwork

From assisting with a disentanglement to gathering significant data samples, Aquarium scientists completed a productive season of research surveys in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence.

By New England Aquarium on Wednesday, October 02, 2024

With fewer than 360 individuals making up the population, North Atlantic right whales are a critically endangered species that requires careful monitoring and protection.

For more than 40 years, the New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life has been conducting vessel and aerial surveys to monitor North Atlantic right whales, which migrate seasonally along the east coasts of the United States and Canada, from Florida to Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence. Aquarium scientists have conducted fieldwork by boat in the Gulf of St. Lawrence each summer for nearly a decade, identifying right whales and collecting samples for further research.

This year, in partnership with the Canadian Whale Institute, our team had three productive research survey trips over the course of June (the earliest we’ve ever started!), July, and August.

We saw 62 individual right whales

During five days on the water in June, our scientists recorded 35 individual North Atlantic right whales, including familiar faces like “Shelagh” (Catalog #4510) and “Boomerang” (Catalog #2503). “Wolf”(Catalog #1703) and “Halo” (Catalog #3546) were both documented swimming with their most recent calves, always an encouraging sight in a species that relies on calf survival to recover.

Shelagh, who was seen entangled in May 2024, then without fishing gear a few weeks later, was covered in severe wounds and swimming very slowly. Even though she appears to have shed the gear, her potential recovery will take time and, even in the best case scenario, leave her with numerous new scars.

We saw two new entanglements

Entanglement, which occurs when a whale collides with fishing gear in the water, is one of the greatest threats to North Atlantic right whales. Entanglements with gear like lobster and crab pots can cause serious injuries, impacting feeding and reproductive health and sometimes even leading to death.

In June, the 1-year-old calf of “War” (Catalog #1812) was seen entangled for the first time. Our scientists were able to attach a satellite telemetry buoy to gear trailing the whale, allowing us to follow it for five days so a specialized disentanglement team could locate and reach the whale, before the tag stopped working. The yearling was spotted again a week later by a Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) aerial survey plane, and our team attached a second telemetry buoy, which contributed to successful disentanglement efforts over the following weeks.

In August, our scientists also observed right whale “Neptune” (Catalog #3301) with a new entanglement. We followed Neptune by boat for seven hours through the northern Shediac Valley until it was too dark to see, but he was moving too quickly and no trailing line was seen for our team to attach a tracking buoy. Aerial surveillance flights went out the next day to try to relocate Neptune but were unable to find him.

We helped remove 19 sets of lost fishing gear

Removing lost, abandoned, or discarded fishing gear from the water is an essential part of preventing future entanglements. When our research team is traveling using a small boat, we are not able to collect this gear ourselves. Instead, we report it to DFO, who will remove it at a later date.

In July and August, we did our research from a larger crab fishing vessel, and one of the perks of that larger vessel was we had the equipment and space to bring this heavy gear on board. Through special DFO permits, our research team was allowed to haul the lost fishing gear when first spotted, rather than reporting it for later removal.

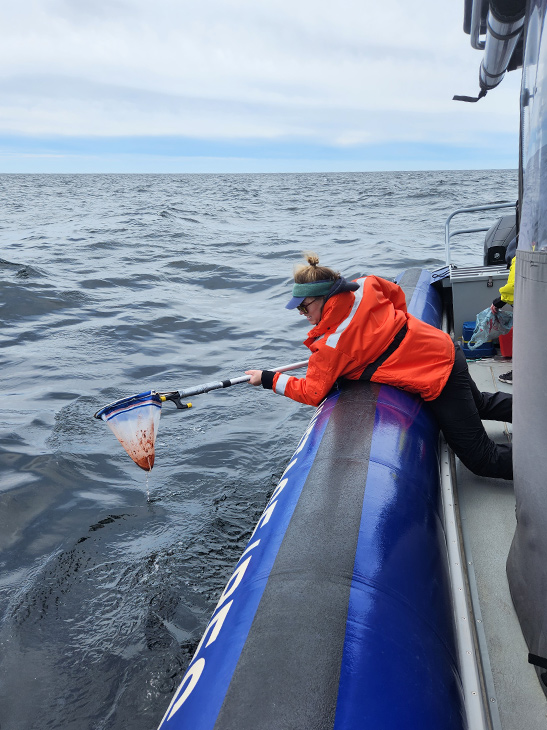

We collected 23 blow samples and three poop samples

One major goal of our research surveys is to collect samples from the whales to study their health through hormone analysis.

This year, our team used drones to collect blow samples for the first time in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In this noninvasive method, a pilot flies a specialized drone over the whale’s head and collects the sample as it blows before diving. This effort resulted in 23 collected blow samples, including one sample from Shelagh, which may reveal important information about her health post-entanglement. We’ll use the samples for hormone analysis and as part of an exciting pilot program to see if the blow samples offer large enough genetic samples to study.

Our team also used drones to collect photogrammetry, or measurements of right whales, gathering data from around 30 individual whales.

In addition, we collected three poop samples, which can be used to analyze hormone levels and other aspects of whale health.

Usually scientists see about 130 unique North Atlantic right whales

Over the last decade, around 130 individual right whales are typically spotted in the Gulf of St. Lawrence across all survey teams throughout the summer season.

The amount of sightings varies from year to year, but our scientists believe some of the whales that they usually see in the foraging areas farther north, like the Gulf of St. Lawrence, were part of a large group of right whales seen 40 to 70 miles south of Long Island, New York in the Hudson and Block Canyons area. Scientists from Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life have spotted over 82 unique North Atlantic right whales during a series of flights over the area south of Long Island between the end of July and the beginning of September.

“This is a good reminder that while we think we have a handle on the movement patterns of North Atlantic right whales, they are always responding and adapting to changing ocean conditions,” said Philip Hamilton, a senior scientist in the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium.

Learn more about North Atlantic right whales and consider sponsoring a right whale to contribute to the Aquarium’s species research and conservation efforts.

This research is done in collaboration with the Canadian Whale Institute and is made possible thanks to the generosity of Irving Oil and the Island Foundation. We are extremely grateful to Irving Oil for partnering with us on this critical research since 1998!