Busy Days on the Water

By Kelsey Howe on Thursday, October 28, 2021

Read Part I of this post in The Return to the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

After a few days on land waiting for some bad weather to pass, we headed offshore once again into the Gulf of St. Lawrence (GSL) on July 11! We made a beeline to the northern portion of the Shediac Valley where we had last seen right whales and we found them soon enough.

Our ninth right whale sighting of the day was Snow cone (Catalog #3560), who we had assisted in a disentanglement attempt on our last day out on the water. There was not much more we could do for her in the moment with such short trailing line, so when we found her, our main purpose was to monitor her entanglement and health. We were able to get better photos of the entanglement injuries in her bonnet and Gina Lonati, our colleague from the University of New Brunswick and drone pilot extraordinaire, flew the drone over Snow cone a few times to get really great aerial footage of her current entanglement configuration and wounds.

In amongst the whales, we also found a lost crab pot, which occurred during our previous surveys in the GSL (and happened a handful more times throughout the summer). Fishing gear is considered “lost” when it still has a floating buoy attached, but is found after the fishing season has ended and all fishers have retrieved their gear. Gear can be lost during the fishing season and fishers are required to report it. In speaking with fishers, we have learned that hundreds of crab pots are reported as lost every year in the GSL, so every one that we find is important to remove from the water column to prevent a whale entanglement. Luckily, we do our research on a crab vessel, so we have the capability to haul gear as long as our captain gets approval from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. On this particular day, a colleague out on a different crab vessel was able to get approval and haul the gear we found. It seems like such a small action, but every lost pot recovered is one less potential entanglement and it is really great to know we are doing something tangibly important to actively protect right whales.

We continued to work right whales for the rest of the day and got to see a few of our old friends like Silver (#2705), Scarf (#1429), and Gandalf (#2010). We ended the day photographing a few small SAGs (surface active group) before we set to drifting for the night.

/

When we know the weather is going to be good and cooperative for a few days, we have the capability on a larger boat with bunks to stay offshore overnight for up to a week at a time. We usually quit surveying a little bit before sunset, because at some point the lighting is no longer conducive to taking photographs or tracking with the whales. We then do some data cleanup, download photos and video off of cameras, and clean our equipment that we used for the day. Somewhere during all of that hustle and bustle we eat dinner. Then you might think our work day officially ends and we get to enjoy our much-needed sleep for the night. Wrong! Every night that we are drifting offshore, we are required to post a night watch for safety. This means that at least one member of the crew has to be up and keeping a watchful eye on the boat and any other boat traffic that might be in the area. We go about this by divvying up watches into two-hour shifts to cover the night. Being awake in the middle of the night is not ideal, but it can be nice to get some alone time in a small space where you are constantly surrounded by eight other people. And getting a crystal-clear starry night, hearing whales blow around the boat in the dark, or watching the sun rise over the open ocean are totally worth the bags under my eyes.

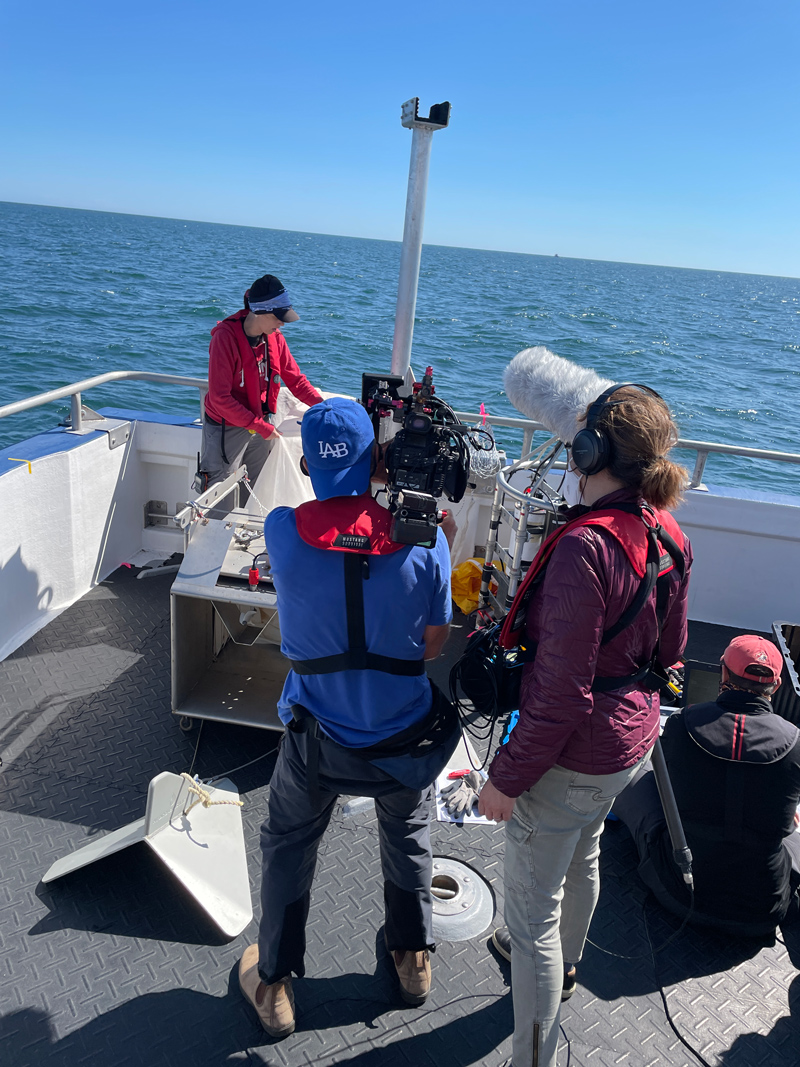

In the early morning on the 12th, we were joined by two members of the “Last of the Right Whales” film crew and then we began our day. The oceanographic team spent the morning and early afternoon doing a series of oceanographic sampling. Our job as the “whale team” on the top deck during this time was to assist their efforts by distance sampling—where we record the number and location of right whales around the boat using special binoculars that show a reticle angle (calculates distance from the boat to the whale) and compass reading (which direction the whale is in relation to the boat)—and to photograph whales opportunistically if they happened to pass the boat when we were not fully focused on distance sampling. This actually happened more often that you would think!

Once this full oceanographic station was completed, we went back on survey in the mid-afternoon. Luckily for us, we had been surrounded by right whales all morning, so we didn’t have to go very far to be in amongst them and collecting data. And to our delight, we collected not one, but two poop samples in under an hour: one from Koala (#3940) and one from #2904. We’ve found that a lot of right whale poop in the GSL dissolves really quickly before we are able to collect it, instead of clumping and floating at the surface, which is what we are more used to dealing with in places like the Bay of Fundy. So, getting two samples back-to-back was a big deal! We scoop up the poop using a specialized net and then transfer the poop into a small, properly labeled, plastic container before freezing it. At the end of the cruise, these poop samples get transferred to our colleagues at the NEAq, who study all sorts of hormones that can lead to discoveries such as this one.

Hopefully this gives everyone a better idea of how many different types of whale research can occur within a day or two on the boat, and this was all while being filmed and interviewed by a documentary crew! We never said our job was boring. Stay tuned for the next blog, which serves as a more in-depth companion piece to my Instagram takeover back in September.

We’re extremely grateful to Irving Oil for partnering with us on this critical research since 1998! We are also grateful to Irving Oil and the Island Foundation for allowing us to operate during these financially challenging times. This work would not be possible without their generosity!