Blown Away: Measuring Hormones from Whale Blow at Sea

A new, innovative and noninvasive method of collecting blow samples helps scientists study the overall health of right whales.

By New England Aquarium on Wednesday, July 18, 2018

By Emily Greenhalgh

When doctors try to paint a picture of a person’s health, they gather as much information as possible. The same is true for the scientists at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium and their 50-ton patients—North Atlantic right whales.

For years, doctors have been able to measure concentrations of hormones and other compounds from human breath. Now—drawing on those same ideas, scientists at the Anderson Cabot Center have found a way to measure hormones in whale blow (breath) from large whales at sea. A paper published on July 17 in Scientific Reports highlights the use of urea, an organic compound that’s also present in humans, as a way to meaningfully quantify hormone concentrations in whale blow.

“A marine mammal is tied to the surface in order to breathe,” said Dr. Elizabeth Burgess, lead author on the paper and associate scientist at the Anderson Cabot Center’s Marine Stress and Ocean Health program. “That’s our opportunity as humans to take samples and understand these animals.”

Scientists from the program collected and analyzed 100 blow samples from 46 different North Atlantic right whales during this study. It’s the first time anyone has successfully quantified hormone levels from whale blow from large whales at sea. The Anderson Cabot Center scientists not only developed the technique to quantify the hormone levels in blow, but used that technique to efficiently collect samples from nearly 10 percent of the right whales in the population. The process involved a long pole deployed from a boat to collect samples, a skilled captain, and long days at sea.

“This study shows feasibility,” said Dr. Rosalind Rolland, senior scientist and director of the Marine Stress and Ocean Health program. “Given the right conditions, you can get blow samples from large whales at sea and you can measure several hormones in these samples.”

Previous work by these scientists had shown that it was possible to measure several steroid hormones in blow, including the reproductive hormones progesterone and testosterone and the stress hormone cortisol. However, interpreting hormones in swimming large whales is challenging because blow samples are diluted by uncontrolled and unknown amounts of water (including seawater). The method developed by the Anderson Cabot Center scientists helps solve this problem by using urea, an organic compound found in low variation in the blood, to gauge exactly how much blow was collected. A diluted blow sample would have a lower urea concentration and vice versa. The researchers found they could detect urea concentration within the samples of blow and could use this information to correct hormone values for any water contamination. This allowed them to accurately quantify hormone concentrations and meaningfully compare levels between individual whales.

Blow contains a plethora of information on an individual whale. From hormone levels, DNA, and respiratory bacteria, the data collected from a blow sample helps paint a picture of the overall health of each animal. More importantly, it’s noninvasive—samples can be collected without harm or contact with the whale. While biopsy darts can be an important source of DNA and hormones, they’re mildly invasive—think getting blood drawn at the doctor’s office versus breathing into a tube. Fecal samples, which are Anderson Cabot Center scientists’ only other noninvasive sample collection method, have provided invaluable information on right whales but can be found only opportunistically during certain times of the year. Whales generally defecate while actively feeding in foraging areas, but sample collection can be hit or miss so our scientists may go entire seasons without collecting a poop sample from whales. For blow, there’s the opportunity to collect any time a whale comes to the surface.

Blow collection (above) offers more real-time data less invasively than either fecal sample collection (right) or biopsy darting (below).

“For the first time, we don’t have to wait around for these whales to poop,” said Dr. Scott Kraus, vice president and senior science advisor at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium.

Kraus, who is also the chief scientist of the Anderson Cabot Center’s Marine Mammal Conservation program, has been studying the endangered North Atlantic right whale since he discovered a remnant group of the population in the Bay of Fundy in 1979.

“The North Atlantic right whale was key in terms of showing meaningful results,” said Burgess. “We know so much about the individual whales, about their reproductive states. We have a reference of what to expect, physiologically, in these whales.”

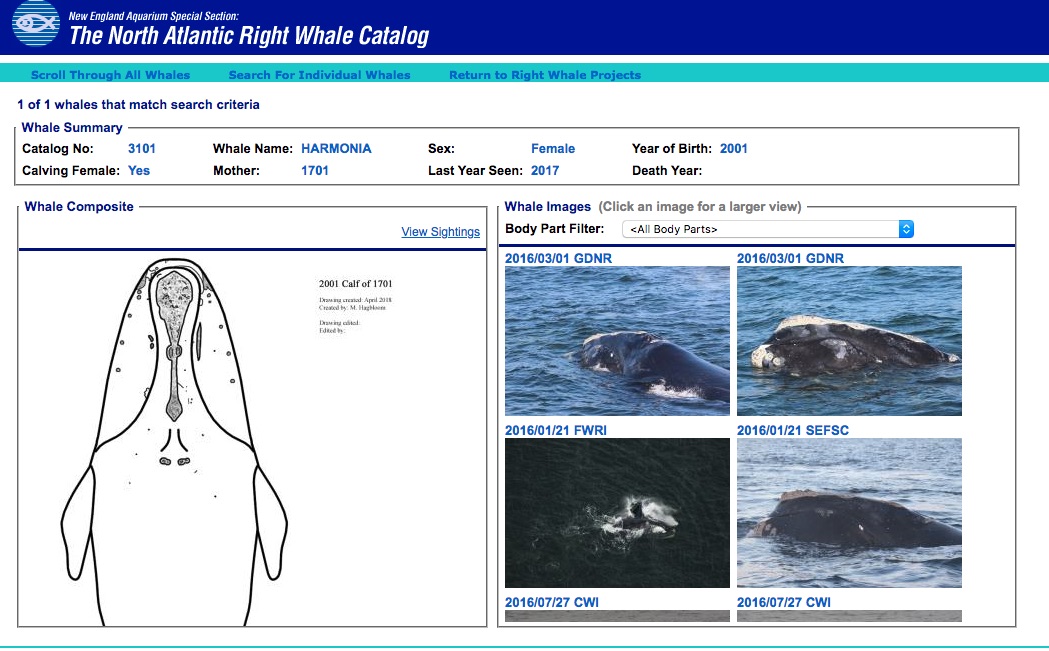

Thanks to the New England Aquarium’s Right Whale Identification Catalog, which is curated by researchers at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life, the scientists were able to positively photo-identify all 46 right whales they sampled during this study.

The most pivotal whale in the study was Harmonia (Whale #3101 in the Right Whale Catalog), a pregnant female. The team collected two blow samples and one fecal sample, which meant the scientists could compare the expected hormone patterns from their tried and tested fecal work and compare it to the blow results. Both types of samples had high progesterone levels characteristic of pregnancy.

“This project was a really classic example of extending into new, innovative technologies by leveraging decades of work done at the Aquarium,” said Burgess, who added that the method could be used on other large whale species.

In the future, scientists could use this technique to examine how whales respond to different human-caused disturbances such as seismic activity, offshore energy development, and shipping traffic, by doing before and after measurements of stress hormones in blow samples. Until now, there was no way to access this near real-time hormone information. Knowing how humans are affecting right whale populations is a key part to protecting them into the future.

Dr. Rosalind Rolland started the Marine Stress and Ocean Health program in 1999 to evaluate the health of living North Atlantic right whales. This program was the first to develop noninvasive methods to obtain health and physiological data on free-swimming, large whales—methods that have since been applied to other whale species and adopted by scientists at other institutions. The program’s scientists developed cutting-edge science that measures hormones in fecal, baleen, and respiratory (blow) samples from the whales, helping researchers understand a right whale’s health, reproductive status, and stress response to human activities. Studies from this program have been vital to the development of management strategies to protect the critically endangered right whale from ship strikes, fishing gear entanglement, and other human-related impacts.