The Plight of Snow Cone

By New England Aquarium on Thursday, August 04, 2022

Entangled North Atlantic Right Whale Snow Cone (Catalog #3560)

On July 23, a vessel with scientists from the New England Aquarium, the Canadian Whale Institute, as well as fishers from the Fédération Régionale Acadienne des Pêcheurs Professionnels, sighted five individual right whales in the Shediac Valley, in the southern region of the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Canada. One of those whales, Snow Cone (Catalog #3560)—a severely entangled 17-year-old North Atlantic right whale—was spotted without her calf. It’s been roughly three months since Snow Cone was last seen, but the sighting confirms that she is still entangled with rope embedded in her upper jaw.

When right whales are sighted, they are visually assessed and their overall health is categorized based on several external parameters, including body condition (i.e. how fat a whale is) and skin condition.

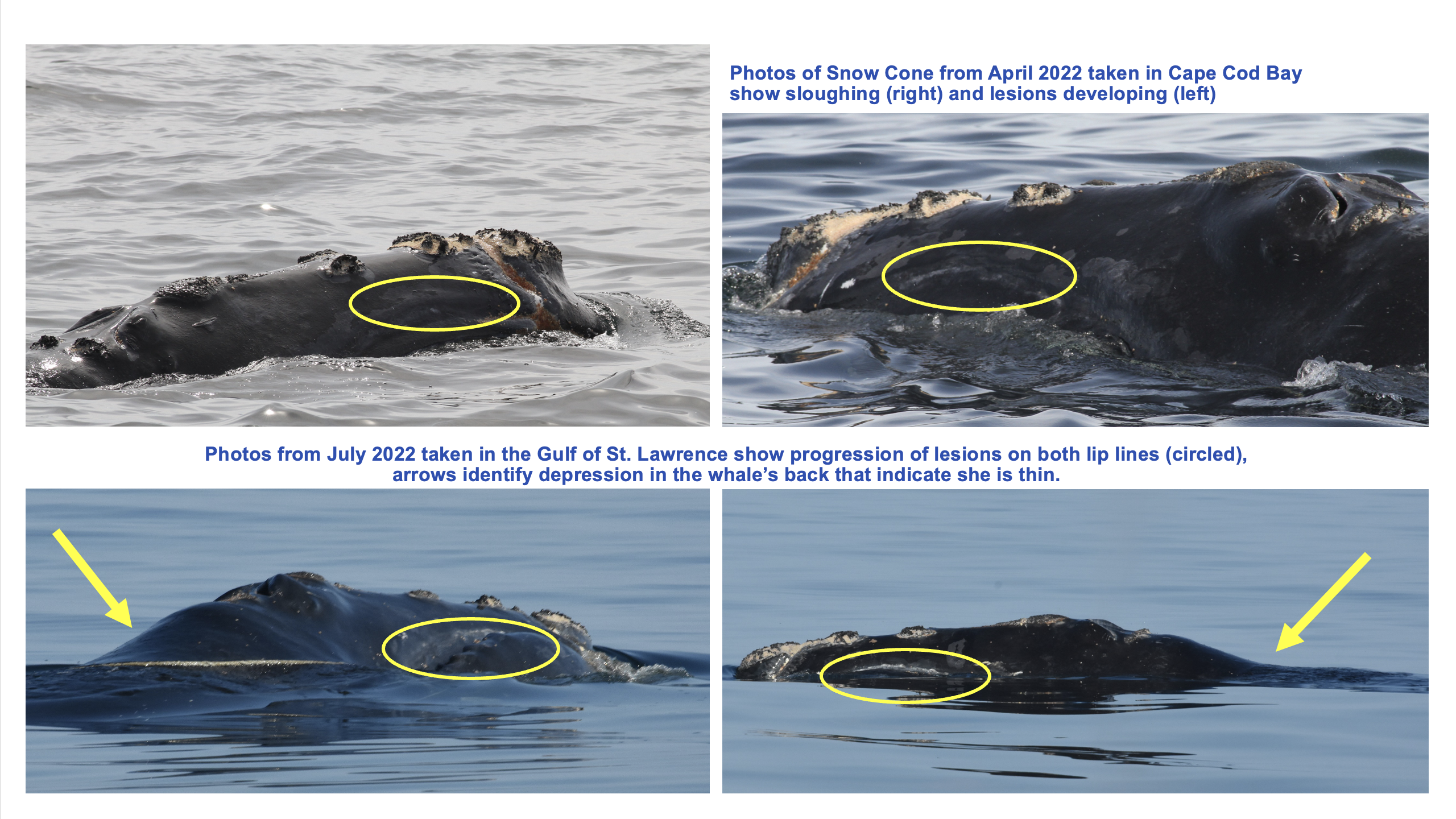

“Body condition at code one is good condition, fat; code two is slight to moderately thin; code three means the animal is emaciated and unlikely to survive. Based on the images from her last sighting, Snow Cone is considered a progressed code two, meaning that she is very thin,” says Heather Pettis, a research scientist at the Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life.

Pettis and other Aquarium scientists determined Snow Cone’s condition has worsened over the past three months. She remains thin and now has lesions on both of her lip lines that were not present in the springtime.

She adds that “Lactating females should (at this point) be gaining back energetic reserves. It looks like she is not recovering condition as we would expect her to and she remains quite thin compared to other moms of the year.”

In March 2021, Snow Cone was seen off Plymouth, MA, dragging hundreds of feet of thick, heavy fishing lines. A trained disentanglement team removed some of the rope, but not all. In May 2021, when she was seen in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, another disentanglement team successfully removed more rope, but the rope embedded in the upper jaw remained. Then, remarkably, Snow Cone was spotted in December 2021 with a newborn calf near Cumberland Island, Georgia.

Previous sightings of Snow Cone with her calf off Cape Cod in the spring spurred news stories and social media posts highlighting her resilience. But as a whale scientist, says Pettis, depictions like these can be misleading. Though whales like Snow Cone can swim with excruciating injuries and attached gear for months and sometimes even years, it greatly diminishes their quality of life and eventually leads to their deaths, she says.

Entanglements from fishing gear have affected almost all of the fewer than 350 critically endangered right whales still alive. Many of them have been entangled at least twice, and some up to eight times.

Currently, Snow Cone, who has been entangled multiple times, has fishing rope so deeply embedded in the bone of her upper jaw that it will probably never come out. She’s condemned to a life—however long it is—of never being able to eat properly again. If she survives (which right whales with this type of entanglement confugration rarely do), her ability to have any more calves is also drastically diminished.

Snow Cone’s family has no shortage of trauma. Her first calf, born in 2020, was killed by a vessel strike at about six months old. Her sister, Infinity (#3230), had a calf that was also struck and killed by a vessel in 2021, and Snow Cone’s nephew, Cottontail (#3920), died in 2021 from a severe entanglement. This recent sighting of Snow Cone without her second calf is not a good sign. Scientists cannot yet say with certainty what happened to Snow Cone’s calf, though researchers conducting field work are continuing to search by boat and plane.

The difficulties that Snow Cone has experienced in her short 17 years offer a perspective on the plight of all North Atlantic right whales. Snow Cone’s situation should not describe her as “resilient” or “defying the odds.” The odds are stacked against these whales, and time is running out to save them. Disentanglement efforts are extremely challenging and don’t always result in fully freeing the animals. A mix of education and legislative action to prevent entanglements might be the only hope for the species.