A Zoomed in Look at Our Aerial Survey Photographs

By New England Aquarium on Thursday, September 16, 2021

By Katherine McKenna

Utilizing photography to improve aerial survey data collection and research

If you have seen our virtual aerial survey, watched our Blue Planet Science Series, or followed our Instagram takeover, you have probably noticed that we take a lot of photos! But have you ever wondered why we take them and what we do with them? To get started, we take photos using two types of dSLR (digital Single-Lens Reflex) cameras: one takes photos through an opening in the bottom of the plane in the blind spot directly below the plane where we can’t see (we call this one “the belly camera”) and one has a long zoom lens that we use to photograph the whales, dolphins, and sharks that we see while we’re flying (we call this one “the whale camera”). Between these two cameras, we can come home from a survey with over 5,000 photos!

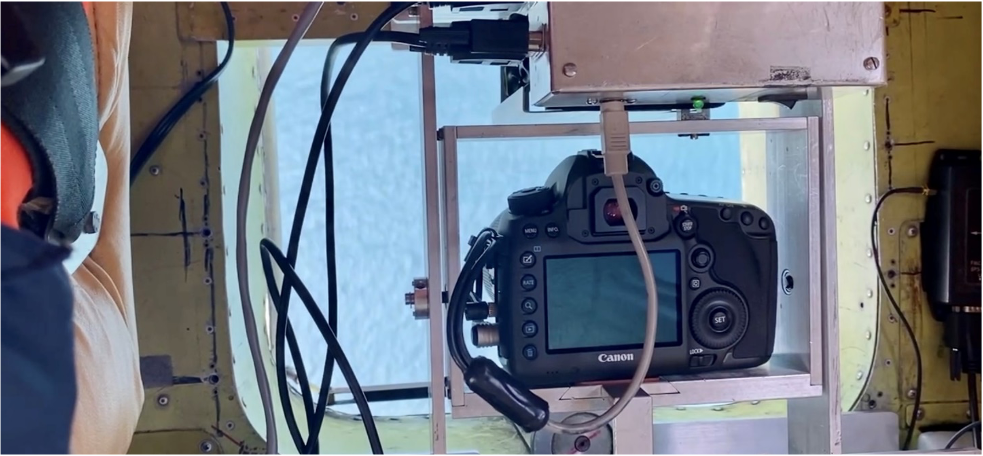

The belly camera takes large landscape style photos to make sure we cover our entire blind spot. For these photos, we use a Canon 5DS with a fixed 85 mm lens which is a great setup for high-end landscape or portrait photography. It takes a photo every five seconds resulting in roughly 4,000 photos per survey! All of these images are reviewed after the survey by observers for marine mammals, sea turtles, sharks, fish, birds, and human activity such as fishing gear, debris, and vessels. Because the photos cover such a wide area (roughly 400 feet across and 250 feet long), the animals in these photos look really small! The images from the belly camera are particularly useful for detecting smaller objects or animals (e.g., sea turtles) that are more difficult for observers to see. Although a lot of these photos are just of empty ocean, we occasionally spot something really cool—like these endangered fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus)!

When we see something interesting while we’re flying, or if we need to confirm species identification during surveys, our plane will divert from our trackline to circle the sighting. These circles allow us to take photographs and to get a closer look. For these photos, we use a Nikon D500 with a 300mm lens and a 1.5x magnifier (making it essentially 450mm). There are a few different reasons we take these photos: to identify species, to catalog individuals, to monitor animal health, and to document behaviors.

All large whale species have distinct characteristics that make it easy for us to identify them without taking photos or using binoculars. In contrast, dolphins are much smaller and move quickly at the surface making it more challenging to determine species, especially if they are further away from the plane. Photographs allow us to confirm species of dolphins (and if there are multiple species together) as well as count any mother-calf pairs within a pod.

/

In addition to identifying the whale and dolphin species that we see, it is also possible to identify individual whales using natural markings and scarring. The identification process is different for each species: humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) have a unique black and white pattern on their fluke (underside of the tail), while fin and blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) can be identified by the mottling or coloration patterns on their backs, scars, or dorsal fin shapes. Each critically endangered North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) has a distinct pattern of callosities (raised areas of roughened skin that appear white) on their head, which are easily visible from aerial photographs.

We match every right whale we photograph using the North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog, which is curated by the New England Aquarium (more information on how we identify individual right whales can be found here). Submitting our sightings contributes to an individual whale’s story that includes how old it is, whether it is male or female, where it travels and when, and if it has been entangled or had any other injuries.

Since approximately 85% of right whales have been entangled at least once, documenting entanglements is another important aspect of aerial survey photography. Entanglements can be difficult to see from the plane unless you circle the whale and take photographs. Getting good photos of entanglements helps researchers assess the health of the animal and severity of the injuries. They also provide valuable insight to disentanglement teams because photos can help scientists determine the entanglement configuration (how the ropes are wrapped around the body) which can be useful for disentanglement planning.

The Kraus Marine Mammal Conservation team at the Anderson Cabot Center utilizes photographs to assess and track entanglements and injuries to critically endangered North Atlantic right whales. Each sighting that survey teams document helps identify new entanglements or injuries, as well as monitor existing entangled or injured whales for health, body condition, wound healing, and whether gear is still present. Continuing to photograph whales after they have been entangled is also critical for monitoring how they recover from entanglements. In many cases, whales become entangled in gear and shed this gear without being seen. Consequently, the only way we know they were entangled is from new scars.

Occasionally we see carcasses on our aerial surveys. Oftentimes, it can be difficult to tow carcasses back to shore so aerial survey photographs are the only documentation of these carcasses. From these photos we can determine species, estimated length, decomposition and scavenging, and if there is any gear or obvious injuries present. The data and photographs are reported to NOAA’s regional marine mammal stranding program after the survey.

We are also able to capture some incredible behaviors through our photographs that help us understand more about how different species are utilizing our survey areas. We see a variety of surface feeding behaviors during surveys, such as lunge-feeding fin whales, bubble-feeding humpback whales, and skim feeding right whales. Knowing that whales are feeding in our survey area sheds light onto the productivity of the habitat. Even though surface feeding provides a rare opportunity to get great photographs, the majority of the time the whales we see are likely feeding subsurface. While we can’t observe subsurface feeding, some indications of this are whales surfacing with mud on their heads and defecation (indicating recent feeding).

/

A unique right whale behavior we often seen in the winter and spring time is surface active groups (SAGs). This social and mating behavior is characterized by two or more right whales in close contact (less than a body length apart) and, as the name implies, involves behaviors such as rolling, flipper contact, or body contact at the surface. Because of all this activity, it can be hard to tell how many whales are in a SAG so we take a lot of photographs of SAGs to identify as many right whales as possible (some may be subsurface, upside down, leaving, joining, etc.). If we get photos of a whale while it is upside down at the surface, we can also confirm if a whale is male or female.

Data collected from our aerial surveys contributes to our understanding of species density and abundance, distribution, and habitat use. Aerial survey photographs provide additional insight into this data, particularly with the identification of species, tracking of individuals and monitoring of their health, and documenting injuries and mortalities. The versatile use of our photographic data makes it a key component of our aerial surveys and allows us to enhance our research and promote the conservation of the species we study. We always enjoy sharing glimpses into the amazing sightings that occur during our surveys and the work that we do with our data, so stay tuned for more updates from our aerial survey team!

Photos taken by NEAq aerial survey team on aerial surveys of offshore wind energy areas; surveys sponsored by Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, and four offshore wind developers. Right whale photos taken under NMFS research permit #19674.