Please note: We strongly recommend purchasing tickets in advance to guarantee entry, as we do sell out during school vacation week (April 19 – 27).

Rare Sightings During October Aerial Survey

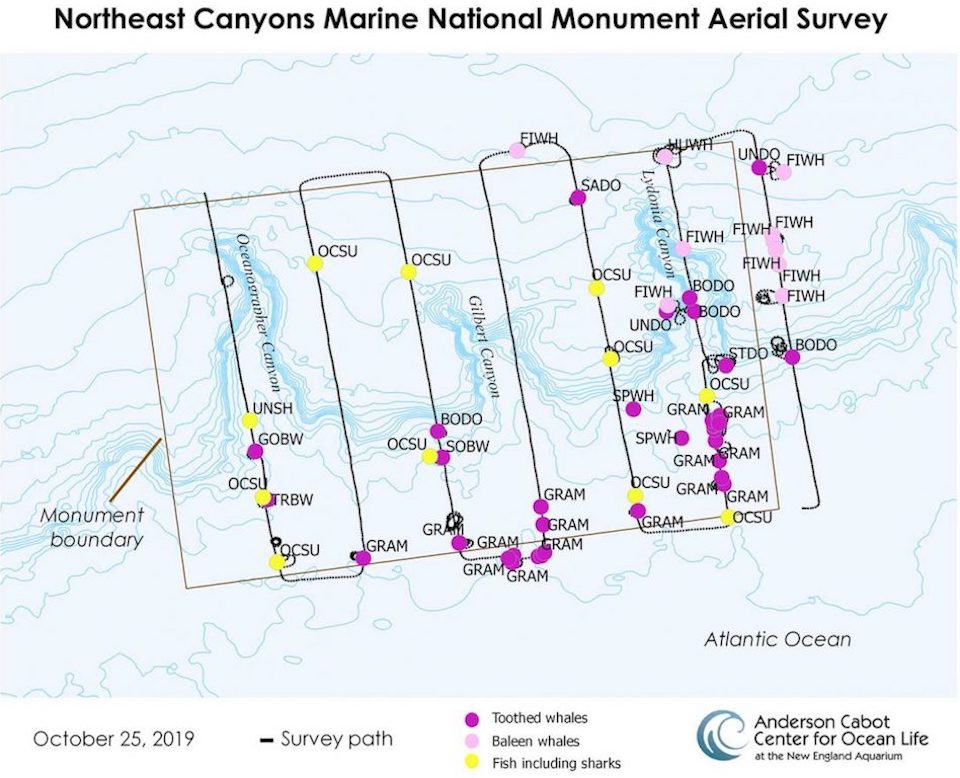

Beaked whales, Chilean devil rays, and a humpback whale were spotted during an October 25 survey of the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument.

By New England Aquarium on Monday, November 11, 2019

As the team was getting ready to embark on another survey of the marine national monument, there was a feeling of anticipation. Surveys of the marine monument are always a mystery because we do not know what to expect, but everyone hopes for an exciting adventure.

And while this survey recorded a lower number of marine individuals in comparison to the year’s previous aerial surveys (309 individuals, all species combined), the low count did not prevent the survey from being exciting. The lower count could reflect a change in local conditions as winter slips in. But this was another survey of many “firsts.”

When the Aquarium’s aerial team arrived at the Plymouth Municipal Airport at 8:15 a.m. on the morning of October 25, the excitement was palpable. Some team members had their own lists of species that they hoped to see while others were open to the endless possibilities. It was also exciting to see the pilots again because they have become our companions in these experiences. There was a sense of camaraderie with everyone, which is helpful and important when spending hours together in a small plane.

We took off at 9:10 a.m. and were on-site at the monument at 10:17 a.m. The survey was conducted in a west-to-east direction starting at the Oceanographer Canyon, the longest of the three canyons within the monument.

Our first sightings involved fishing gear. This is common in the outer track lines of the survey where human presence, although minimal, is tangible. In total, the team recorded 13 pieces of fishing gear on this track line.

As we flew over the blue ocean in search of life, the first confirmed animal sighting occurred when two Cuvier’s beaked whales (Ziphius caviorostris) broke the water’s surface to breathe. Cuvier’s beaked whales are distinguishable by a short, poorly defined beak and a sloping forehead. These were probably young or females because their dorsal fin and back had uniform grey coloration with no scars at all.

Just five minutes later, we recorded another beaked whale sighting. This sighting involved a group of four True’s beaked whales (Mesoplodon mirus). This was exciting not only because beaked whales are hard to spot, but also because this was our first sighting of this species at the marine monument. True’s beaked whales are little-known members of the beaked whale family. They are typically found in deep, warm, temperate waters of the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Indian Ocean. They were discovered by Frederick W. True, a curator at the Smithsonian Institution, who described the species from a stranded animal on a beach in North Carolina. Their scientific name, Mesoplodon mirus, reflects True’s excitement at the discovery of the species: mirus is the Latin word for wonderful.

There is little information on the abundance of True’s beaked whales worldwide. Our sighting is very important because it will help us understand what species use this protected area. True’s beaked whales were in the deeper waters in the canyon in approximately 967 meters (3,173 feet) water depth.

An ocean sunfish (Mola mola) was also recorded while the plane was circling to take photographs of the beaked whales. The four beaked whales and ocean sunfish were sighted in the deeper waters of the canyon at approximately 1,087 meters (3,569 feet).

The next sighting involved the first record of a Chilean devil ray (Mobula taracapana) by the Aquarium’s aerial team at the marine monument. The least known of the rays, Chilean devil rays are believed to have circumtropical distribution and have been recorded at scattered localities. Satellite archival tagging results from the central North Atlantic reveal that devil rays are a truly oceanic species capable of traversing long distances throughout the Atlantic Ocean. They are amazing creatures that can dive to maximum depths of up to 1,896 meters (6,220 feet) and withstand water temperatures around 4°C (39°F). A second Chilean devil ray was recorded four track lines later.

The last marine megafauna sighting at the Oceanographer Canyon involved another ocean sunfish. Sunfish spend up to half the day basking in the sun near the surface of the water, which helps warm their bodies after deep-water hunting dives. This surface behavior helps the aerial survey team spot them from the air.

The next four tracklines were relatively quiet. On the second track line, we spotted nine Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus) and one ocean sunfish. The third trackline involved sightings of five Risso’s dolphins, two bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus), two ocean sunfish, and three Sowerby’s beaked whales (Mesoplodon bidens). This was the third species of beaked whales for the day. Sowerby’s beaked whales are distributed throughout the North Atlantic Ocean, but prefer the deep, cold temperate and subarctic waters off the continental shelf edge of the North Atlantic Ocean. They are usually found individually or in small, closely associated groups averaging between three and 10 individuals.

The crossleg (the area between tracklines) was more active. Several small groups of Risso’s dolphins were sighted in the deep waters (more than 2,000 meters/6,560 feet). Group sizes ranged from 1 to 40 for a total of 80 Risso’s dolphins. In the fourth trackline, 10 Risso’s dolphins were sighted. The fifth trackline had two sightings of marine mammals: 40 common dolphins (Delphinus delphis) and five Risso’s dolphins, in addition to sightings of three ocean sunfish and the second Chilean devil ray we mentioned earlier.

/

Similar to previous surveys this year, Lydonia Canyon was a hot spot. The highest number of sightings and diversity of species occurred here. Seven species of marine megafauna were observed, including more Risso’s dolphins (42), bottlenose dolphins (45), common dolphins (15), and an ocean sunfish (1) as well as striped dolphins (15), fin whales (2), and a humpback whale.

The fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) were observed inside the shallower waters of the canyon (about 150 to 210 meters). The species had not been spotted in the monument since 2017. The lack of fin whale sightings does not mean that fin whales were not present. Instead, it highlights the importance of continuing to conduct these surveys to ensure that we fully understand the species, numbers of animals, and age groups (e.g., mothers and calves) using this protected area. At this canyon, another first also occurred, the sighting of a humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae).

Their scientific name is derived from the Greek words “mega” meaning large and “pteron” meaning wing (referring to their long pectoral flippers, which are one-third of their total body length), and “novaeangliae” meaning New Englander because they were first described from the waters of New England. Their common name, humpback whale, refers to the small hump under their dorsal fin and the characteristic hunched shape that is clear when they are about to dive. This particular individual had on its body visible patches of white, which represent sloughing or areas of scuffing. Like humans, most whales, dolphins, and porpoises are thought to shed skin continuously throughout the year.

The last half hour of the survey was spent on the eastern side of the Lydonia Canyon, where seven fin whales and 10 bottlenose dolphins were sighted. As the survey ended, after approximately four hours of surveying, the plane began to climb in altitude to head back to Plymouth.

But this adventure could not end without a sighting of the largest of the toothed whales. In water depths of more than 1,040 meters (3,400-plus feet), two sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) were spotted as they came to breathe at the surface. It was unexpected and a great way to end the day.

Acknowledgments: Dr. Robert Pitman (Oregon State University) and Todd Pusser helped with the beaked whale identification. This important work is made possible thanks to the generous support of the Conservation Law Foundation, National Ocean Protection Coalition, Natural Resources Defense Council, and Resources Legacy Fund.