Please note: We strongly recommend purchasing tickets in advance to guarantee entry, as we do sell out during school vacation week (April 19 – 27).

MCAF: Right Whales that Cross Hemispheres

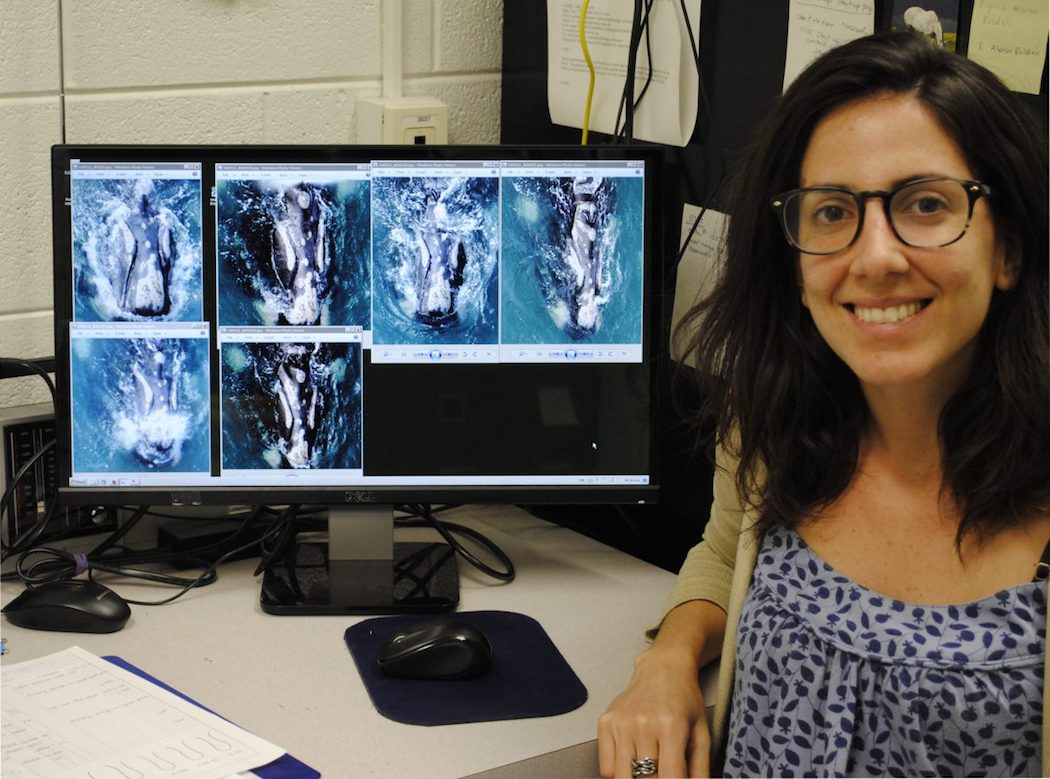

Visiting Argentinian MCAF Fellow shares her experience in using photo identification to monitor the health of Patagonian right whales

By Florencia Vilches on Tuesday, February 05, 2019

The Marine Conservation Action Fund (MCAF) Ocean Conservation Fellows Program brings ocean conservation leaders from around the world to the New England Aquarium, where they exchange ideas with Aquarium educators and scientists at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life, share their work with the public, and inspire and empower the next generation of ocean protectors. MCAF Fellow Florencia Vilches, a researcher at the Instituto de Conservación de Ballenas, traveled to New England last summer.

Right whales can be individually identified thanks to natural patches of roughened skin on their heads called callosities. Photo identification is a tool that allows knowing who is who within a population of animals and, if done continuously and periodically, detecting changes in the population health and dynamic.

Just like the New England Aquarium curates the North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis) Photo-Identification Catalog, the Instituto de Conservacion de Ballenas (ICB) from Argentina and Ocean Alliance (OA) from the U.S. curate the Patagonian Southern Right Whale (Eubalaena australis) Catalog, which is the cornerstone of ICB/OA’s work and is considered an invaluable data source for conservation and education. Since 1971, more than 3,200 southern right whales have been identified.

Unlike right whales from the Northern Hemisphere, most southern populations are now on the increase. Today, they are the focus of many whale watching ventures in the Southern Hemisphere, where they can be viewed from shore as well as from boats.

In 2016, with support from the Marine Conservation Action Fund (MCAF), we initiated a project to incorporate to our catalog more than 460,000 whale photos taken between 2004 and 2016 by whale watching photographers from Península Valdés in Patagonia. As an MCAF Fellow, I was invited to the New England Aquarium to share my experience in the use of photo identification as a tool for monitoring the health of the Patagonian right whale population and in the collaborative work with local photographers.

Bringing right whales from Valdés to the Boston community

During an intense and exciting week of July, I had the chance to interact with a multiplicity of audiences. The brown bag lecture for the researchers, educators, and communicators of the Aquarium led to an enriching exchange of experiences about the great challenge of raising environmental awareness worldwide. The lecture at the Simons IMAX® Theatre allowed me to bring the life histories of the whales from Valdés and the threats to their conservation to dozens of attendees from the Boston community and more than 3,000 viewers of the online streaming. A very interactive talk took place at the East Boston Public Library, where the audience actively participated with several questions about right whales. Also, I had the valuable opportunity to interact with local children and teens, the audience I was more excited about.

During a meet-and-greet event with visitors of the Aquarium, many children got to know the family tree of the famous whale 71 from our catalog of identified right whales, and learned about the five generations of whales we currently know thanks to 48 years of continuous scientific work. Other visitors were amazed by the tiny size of the cyamids, invertebrates that cover the callosities of right whales.

I met the teens of the Aquarium’s youth programs during a fun pizza night, just before inviting them to be right whale photo-IDers for a day and build the trees of some of the families in our catalog. My mission was to inspire them as future conservationists, but there were these young persons, still in high school and investing their summer days in empowering themselves as future ocean stewards, who inspired me.

A different field season

Each summer since 1980, the New England Aquarium’s Right Whale Team conducts the field season at the Bay of Fundy to study North Atlantic right whales. With only about 430 whales remaining, this population is severely threatened, mainly by vessel strikes and entanglements in fishing gear.

The famous house that works as a field station reminds me of the field seasons I spend in the Patagonian house where Dr. Roger Payne once lived with his family. The walls covered with photos and quotes reflect the decades of history hosted by that house. The Bay of Fundy is a whale party. In addition to right whales, it is the home of minke, fin, and humpback whales. Thus, when we finally find a blow on the horizon during the first boat day, we contain the excitement, since we still need to make sure is a right whale. So we come closer and … Yes! There is the unmistakable V-shaped blow.

The 5 a.m. waking up, terrible for a non-morning person like me, was so worth it. I finally met “my” whales’ cousins. My colleagues immediately try to identify the individual and, with a joy that feels familiar to me, find out this is a known whale. Hours later, we found the second and last right whale I was going to see in two weeks.

Although that was a low number for me, used to the crowds of Valdés, it is good news for my colleagues, who found no right whales for months during 2017. Simultaneously, part of the team is sailing the waters off the Gulf of Saint Lawrence where an increasing number of right whales has been recorded during recent years. It is good news, but it is clear that whales are changing their distribution and that is a big challenge for monitoring their health.

When the weather was not suitable for sailing, we analyzed data at the field station. I was introduced to NEAq’s custom-made photo-identification software DIGITS and was able to explore options for managing our southern right whale database. The bright side of searching for whales in a catalog of 732 individuals instead of 3,200 as I am used to are the better chances of finding a match, which is always a great satisfaction. Less happy was realizing that many of the searches are based on scars of vessel collisions or entanglements.

The challenge that the Right Whale Team has on their horizon is intimidating: prevent the North Atlantic right whales from becoming forever extinct. After long after-dinner talks I got to know that no calves were seen during the last calving season. Not one. Last year, 17 whales were found dead, 13 were known individuals. For a moment, I placed myself in their shoes and thought about finding a dead right whale in the coast of Valdés and realizing that is Antonia, Mochita, or any of “our” whales. It was heartbreaking.

Lessons learned

The conservation and well being of southern right whales are not severely threatened by vessel strikes and entanglements, but they are indeed threatened by other causes, such as kelp gulls harassment in Valdés and the decline of krill abundance. There is a common denominator in the threats that both species face: poorly managed human activities. In this world that devours resources in growing leaps and bounds, it is our duty as citizens to protect such resources for future generations. And that requires more than turning off unused lights and taps, or throwing trash in the proper bin. It requires community-scale actions: initiatives proposed and executed in the neighborhood where you live, the school where you study or the office where you work are the ones that will inspire others and will create the social pressure necessary for resources to be used with as little impact as possible and be available for this and many more generations. For the whales in the north not to become extinct before ours eyes and the whales in the south to continue being crowds in our Patagonian coasts.

THANK YOU to all the NEAq staff, who instantly made me feel at home, and especially to the MCAF and Right Whale teams for your kindness, generosity and inspiration.