NEAq scientists survey the remote Marine National Monument

“It is not down on any map; true places never are.” NEAq scientists survey the remote Marine National Monument.

By New England Aquarium on Friday, January 15, 2021

By Laura Ganley

Biodiversity is a word ecologists use to describe the variety of species found in an area. Conserving areas with high biodiversity (or large numbers of species) is extremely important for maintaining functioning ecosystems and a healthy planet. The Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument is an area about the size of Connecticut and is about 130 miles south east of Cape Cod. These three undersea canyons and four seamounts were designated as a Marine National Monument because of the high biodiversity of marine mammals, fish, corals, invertebrates, seabirds, sea turtles, and sharks. I knew that flying in this area would give me the opportunity to see animals that I had never seen before, but had been trying to get a glimpse of my whole life.

The Monument is home to animals that are the Olympians of the marine mammal world and record holders for all of the most extreme events; for example, the Monument contains beaked whales that can hold their breath for hours, sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) that can dive miles beneath the ocean surface, and blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus)—the biggest animals to have ever been on earth. Who that has read the classic Moby Dick has not wondered what it would be like to see one of these giants in real life? For these reasons, I was thrilled to have the opportunity to survey the Marine National Monument last week.

I was also interested in surveying the Monument because I was recently asked to collaborate on a project with EcoMap’s GIS specialist, Brooke Hodge. Brooke is conducting an analysis (funded by the Natural Resources Defense Council) to understand how whale and dolphin diversity in the Monument relates to diversity in 500 other marine habitats along the east coast of the United States. To make this comparison we are using two diversity metrics (alpha and beta diversity) and over 40 years of marine mammal survey data. One measure of Alpha diversity refers to the number of species in an area, sometimes called species richness. Beta diversity measures the number of species in common between two habitats. For example, we are comparing which species are seen on the Monument with which species are seen on our aerial surveys of Southern New England. We will also explore the seafloor and oceanographic characteristics that may explain the biodiversity patterns.

All of these diversity indices and their possible explanations were swirling in my head as I made the pre-dawn drive to Plymouth Airport last week. When I finally got to the airport I realized I needed to take a moment to take a deep breath. Yes, we had a job to do today, but I couldn’t afford to let the survey go by without appreciating where we were and what we were seeing. I decided it was important to take a minute to enjoy the winter sunrise over the runway.

On the ~130-mile journey out to the Monument I thought about the only other submarine Canyon I have surveyed: Barrow Canyon. Barrow Canyon is located just north of Utqiagvik, Alaska (the northernmost “city” in the United States). Surveys of Barrow Canyon rarely disappoint with loads of feeding bowhead (Balaena mysticetus)and beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas). But, Barrow Canyon is north of the Arctic Circle, so I was confident that if this Monument flight would have a very different assemblage of species.

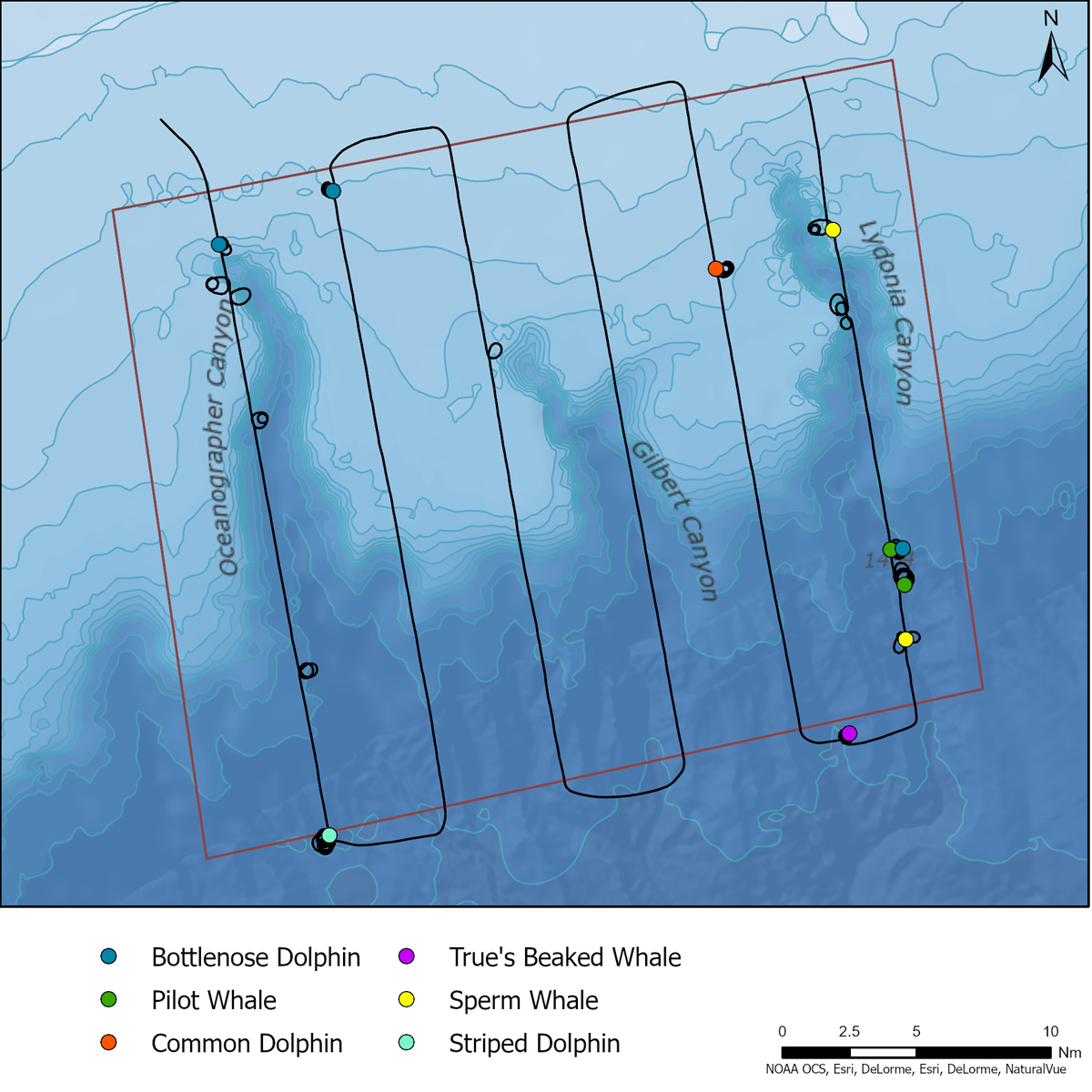

The Northeast Canyons did not let me down! Most of the species we saw were new to me: we photographed striped (Stenella coeruleoalba), bottlenose (Tursiops truncatus), and common dolphins (Delphinus delphis), plus pilot (Globicephala sp.), True’s beaked (Mesoplodon mirus), and sperm whales! All of these whales and dolphins are odontocetes, or toothed whales, as opposed to mysticetes, or baleen whales. In general, toothed whales seem to have a stronger and less seasonally variable association with canyon habitats than baleen whales, which might explain why we don’t see baleen whales on every flight here.

True’s beaked whales, pilot whales, and sperm whales all feed on deep-sea squid, making the canyons a perfect spot for them to find food. Pilot whales are known for stranding en masse, and unfortunately most of my previous experience with them has been on a beach or up a river during one of these mass stranding events. It was awesome to see living pilot whales in a mixed species pod with bottlenose dolphins.

The six True’s beaked whales were a sight all on their own, traveling in a line, one in front of the other. Pleasantly, they spent quite a while at the surface, recovering from however long their previous dive had been.

But, the highlight of my day were the two sperm whales. The aerial view provided a great opportunity to observe the slightly left-skewed blowhole which results in a blow that is also biased to the left. The strange placement of the blowhole was perplexing to Melville who noted: “Physiognomically regarded, the Sperm Whale is an anomalous creature. He has no proper nose.” While sperm whales do have a “nose” (in the form of blowhole that serves the function of breathing), I can understand why Melville was confused.

On our way back home, Orla and I had a chance to reflect on the significance of the day. Orla scrolled through photographs and filled me in on bits of Monument trivia and information about the species we had seen “beaked whales glide diagonally to the surface in order to evade predation by killer whales that may have been listening to them feeding at depth and waiting for them to surface,” or “we often see the striped dolphins over the canyon mouths.” I shared my excitement about how this flight would contribute to the exciting diversity analyses we have in progress.

At one point, I realized this was the first time in a few days that I have been able to forget the chaos happening in the rest of the world. It reminded me how important these field days are to me. My phone was off, even if it wasn’t we were far out of cell phone range, and the pilots continually commented on the fact that we were in “uncharted airspace.” Even though we are enclosed in a plane so small we almost sit on top of each other, sometimes it can feel like you are completely alone staring out the window. I wish everyone in the world had the opportunity to occasionally go out to the middle of the ocean and recharge their batteries. I really needed it!

This survey was made possible by the support of Natural Resources Defense Council. Previous surveys have been funded by Natural Resources Defense Council, Conservation Law Foundation, and National Ocean Protection Coalition.