Please note: We strongly recommend purchasing tickets in advance to guarantee entry, as we do sell out during school vacation week (April 19 – 27).

Patterns and Processes in the Marine National Monument

Scientists hope aerial surveys will unlock the secrets of a biodiversity hotspot

By New England Aquarium on Thursday, July 29, 2021

By Orla O’Brien

“Just one more pass—just one more,” says Katherine McKenna, Research Assistant and aerial survey biologist at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium. She is staring down the 300 mm lens of our Nikon dSLR camera as our survey plane circles a whale shark (Rhincodon typus)—the biggest fish on the planet —so it’s not hard to understand why she can’t pull herself away. Watching this huge fish slowly undulating just below the bright blue surface waters over Lydonia Canyon, I find myself overcome with a sense of déjà vu, and thinking about the patterns I have noticed in my three years researching the Monument.

The Obama administration designated the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument in 2016—the first of its kind in U.S. Atlantic waters. It’s a national park, but instead of being crowded with tourists poring over maps and outfitted in hiking gear, this park is full of dolphins, whales, fish—and deep below the surface—corals, sponges, and crabs.

The New England Aquarium has been conducting aerial surveys in this ocean hotspot since 2017, collecting data that shows this area is teeming with biodiversity and deserves protection. We continued these surveys, even after the federal government rolled back many of the fishing restrictions here 13 months ago, to document the amazing wildlife in the Monument and to contribute the data needed to aid efforts to reinstate these important protections.

Saturday, July 24, was our eleventh survey so far, and by now the monument feels like an old friend. Katherine and I were with two pilots, Andrew and Wayne, who were new to the area, so we gave them a run down on the hour-long, 130-mile transit to the survey area:

“We’ll be seeing a lot of dolphins, so get ready to circle!”

“Have you ever seen a sperm whale? I can’t promise we’ll see one, but I can promise they’re there.”

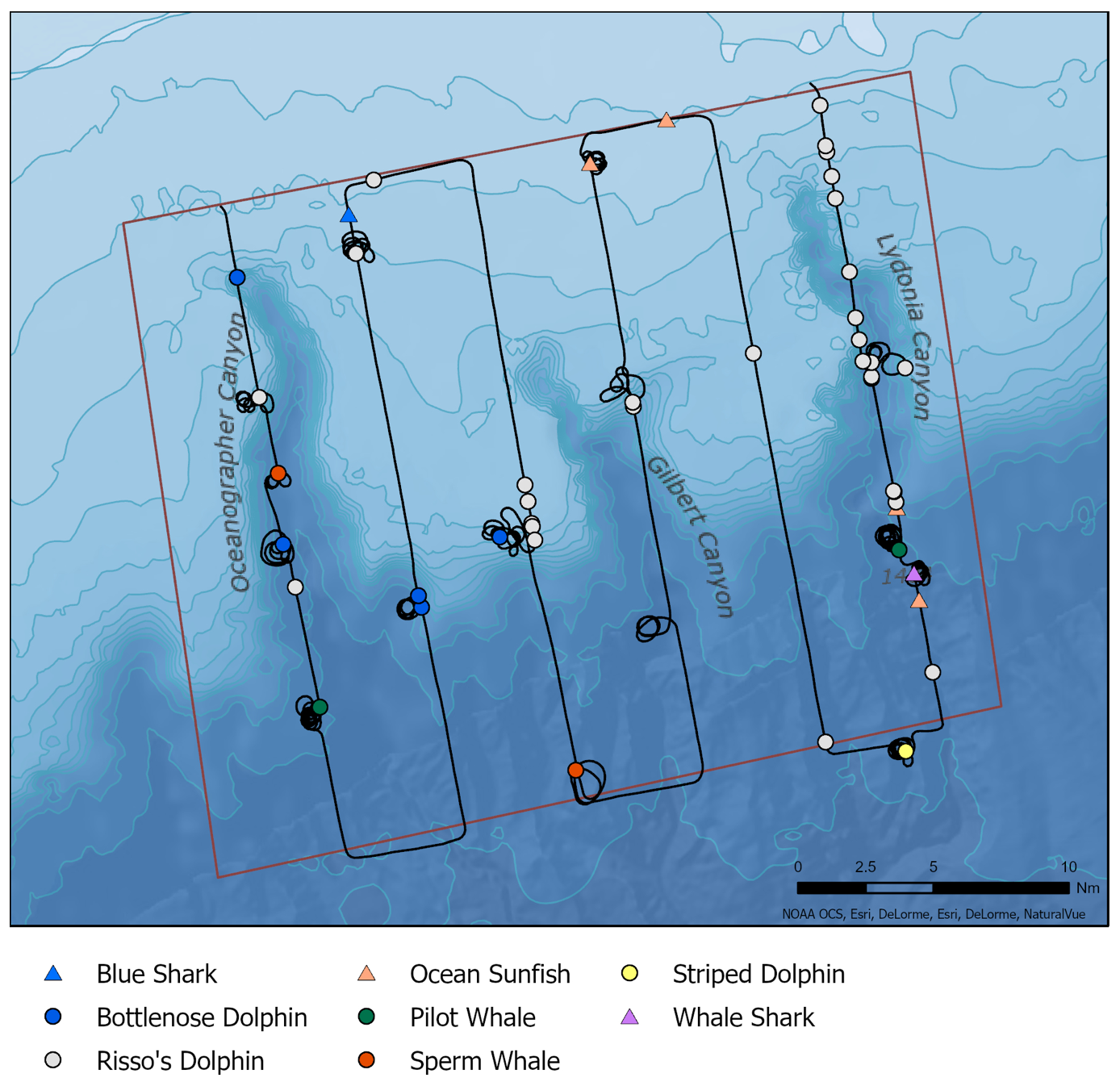

We entered the survey area at 9:40 in the morning, an invisible box in a sea of blue as far as the eye can see. Within five minutes we had already left the trackline to photograph a small pod of Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus). Risso’s dolphins (or grampus, as we call them in the plane, to avoid the sibilant S sound) are a familiar sight in these offshore canyons. They survive here on the huge numbers of squid that the monument is home to—like many of the whale and dolphin species we see out here. By the end of the survey, we will have recorded almost 500 of this species, mostly in small groups of about 15 animals, many traveling with calves.

We also photographed two groups of pilot whales (Globicephala sp.)—actually large oceanic dolphins, despite their name. They are ecologically quite similar to the Risso’s dolphins: they also eat squid, but because they are a little larger, can dive a little deeper, and hold their breath a little longer, they feed in a slightly different place than their cousins. It is a fascinating example of niche partitioning (where two species that might otherwise compete, are able to coexist by using slightly different resources) that explains why the monument can support so many different types of species.

Another example of niche partitioning among the squid eaters is the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus). Much larger than either pilot whales or Risso’s dolphins, this whale is famous for tackling the giant squid, although in reality it eats many species of squid, most of them much smaller. This whale can hold its breath for up to 40 minutes, meaning our plane probably flies over many of them feeding in the depths. However, this means they have to recover at the surface catching their breath between dives. We spotted one resting like this over Oceanographer Canyon (the deepest canyon in the monument), and Katherine remarked that this made the animal “a very cooperative subject” for photography.

By the end of our first trackline, we had seen four different species: the sperm whale, Risso’s dolphins, pilot whales, and bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Four years into our surveys of this remote marine park, we have come to expect that this first trackline over Oceanographer Canyon will have a lot of sightings. At close to a mile deep, Oceanographer Canyon is the deepest of the three canyons in the monument, and oceanographic processes create and aggregate food for the entire food chain. Although we may see something amazing at any point within the monument, it is often the first and the last trackline (over Lydonia Canyon) that yield the highest number of animals.

On the four tracklines in between, we were kept busy by a steady number of the usual suspects: bottlenose dolphins, Risso’s dolphins, and a sperm whale that unfortunately took a dive before we could photograph it. We had an odd sighting of a group of four ocean sunfish (Mola mola), sunning themselves at the surface—usually we see them alone.

As we crossed between the fifth trackline to the sixth, and final, trackline, I spotted a tight group of dolphins out the right window of the plane. I knew without a doubt that they were striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba), though two years ago I’m not sure I had even heard of the species. The tight packed group, the fast movement, and the slightly smaller body size made me turn to Katherine and say, “Looks like striped dolphins,” before she was able to confirm with her photographs that these dolphins had the diagnostic pale “scarf” stretching from their eye to their dorsal fin.

These dolphins are fun to watch and photograph. Their delicate frames belie the tremendous feats of acrobatics they are capable of, and we watched one animal leap high into the air and hang above the surface for what seemed an eternity before diving back into the water with its pod. What struck me was a feeling of inevitability—I was expecting to see these dolphins—hadn’t we seen them here before? Hours later, at my computer, I would confirm that we have seen pods of striped dolphins at the mouth of Lydonia Canyon three other times previously—all within about 5 nautical miles of our most recent sighting.

About ten minutes later, we spotted something else that we had been crossing our fingers for: a whale shark. We have spotted these majestic giants on our surveys during two previous summer surveys: in July of 2017 (when, in a gut-wrenching twist, the shark was spotted by an automated camera that operates below the plane, but not seen by observers), and in August of 2020, when we had the amazing luck to see four of these animals. While seeing these seemingly tropical fish in cold Northeast waters may seem unusual, they actually follow protrusions of Gulf Stream water, which are not uncommon here during the summer.

When I say our amazing sightings didn’t surprise me, it’s not to give the impression that I am not in awe of the wildlife in this small corner of the ocean. To me, it is the ability to recognize patterns and search for meaning that makes science so exciting. Our research can help protect these threatened species: a recent paper led by Dr. Jessica Redfern, and coauthored by myself and several of my colleagues at the aquarium, used data from our aerial surveys about the locations of marine mammals and other data sources about the locations of other species to show that it is imperative that the protections under the original designation be restored.

Our continued surveys in this area spark questions for further research: how does the biodiversity in this area compare to the rest of the waters in the Western North Atlantic? Why do we see more animals in some areas of the Monument than others? What processes underlie the reason why we see some species on almost every flight (Risso’s dolphins, sperm whales), while others, like the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) and the whale shark, are rarer treats? While answering these questions may serve to reinforce the importance of protecting this area, it can also help us determine how to pick other areas to protect in the future. I continue to fly to this remote area to help collect data to answer these important questions, but, yes—sometimes, I just feel the urge to look at a whale shark.

This survey was made possible by the support of Natural Resources Defense Council. Previous surveys have been funded by Natural Resources Defense Council, Conservation Law Foundation, and National Ocean Protection Coalition.