Summer Sightings from the Aerial Survey Team

By New England Aquarium on Wednesday, July 20, 2022

The New England Aquarium’s aerial survey team has been conducting systematic aerial surveys in southern New England since 2011. Our surveys collect valuable data on many marine species like whales, dolphins, sharks, and sea turtles. This long-term data set contributes to developing wind energy sustainably by helping to monitor changes in populations, animal health, and trends in occurrence and habitat usage. We’d like to share some of our more interesting sightings this summer through these blogs and photos! These surveys are currently sponsored by MassCEC and BOEM.

If an orca bites you in the ocean, and no one sees it, does it still leave a scar?

Updated September 2

Earlier this year in May, New England was abuzz with the news that a killer whale, or orca, was sighted near Cape Cod. While it is not often that we see orcas in New England, we do see evidence of previous encounters with large whales that visit our waters.

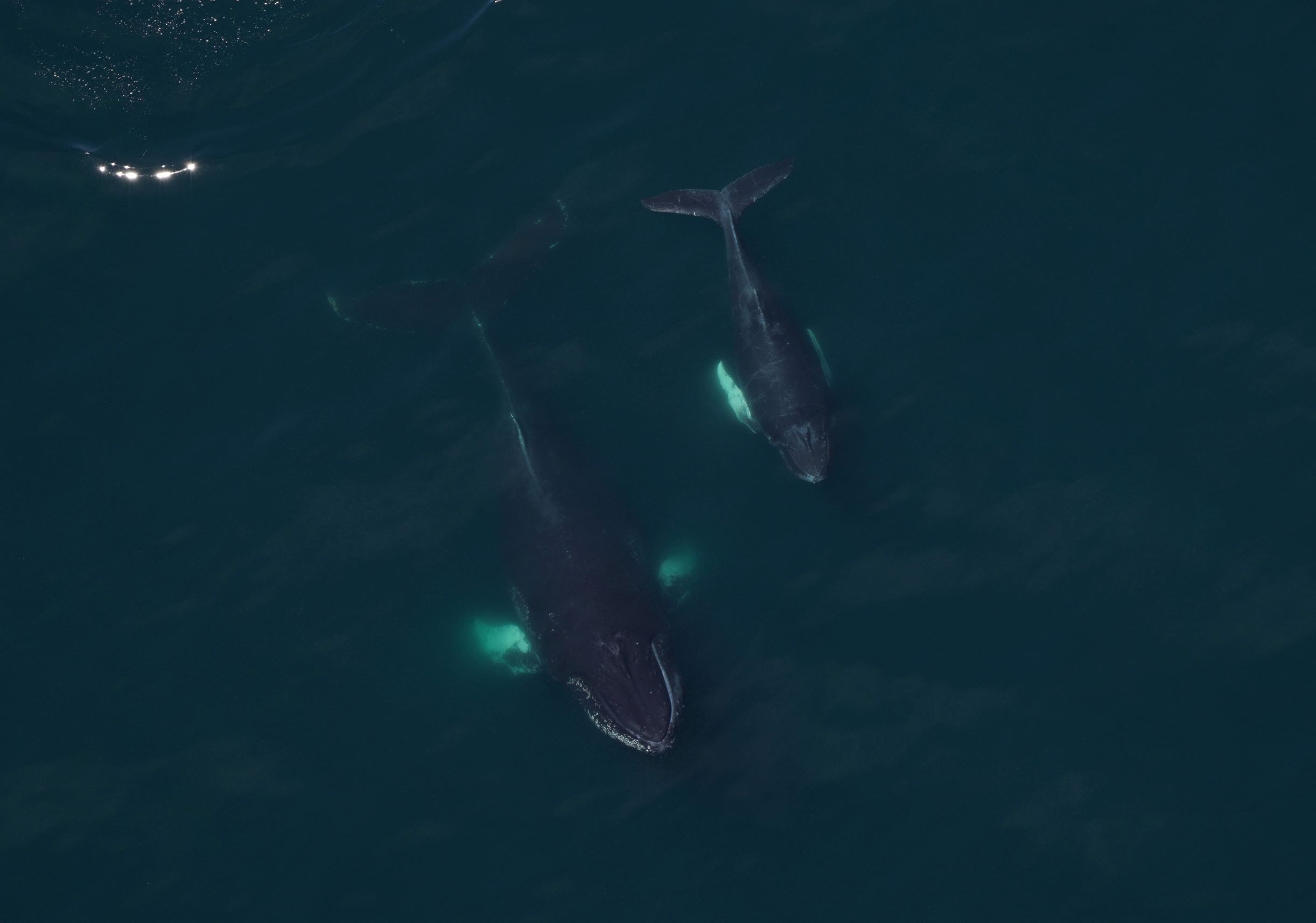

Each winter, Gulf of Maine humpback whale mothers and calves make a long migration from the breeding and calving grounds in the Caribbean to their northern feeding grounds–a trip of more than 1,000 miles. During this journey, the calves are vulnerable to attacks from predatory orcas.

While orca attacks on humpback whales are rarely observed, these interactions can be documented through the scars left behind by an orca’s teeth. These scars are often found on the tip of a whale’s fluke (tail) and are called “rake marks” due to the appearance of the parallel lines. Calves are more vulnerable to these attacks than adults due to their small size, and these scars will last their whole life. Around 15 percent of humpbacks in the Gulf of Maine have rake marks.

This summer, we photographed two humpbacks with rake marks on their flukes. One of these was a calf that was most likely attacked by an orca during this year’s migration with its mother. The second humpback was an adult who likely got her scars when she was a young whale. Photo documentation of these scars enables researchers to understand how humpbacks and orcas overlap and interact with one another, even when we don’t see it happen.

Mom knows best: Humpback whale calves learn where to feed from their mothers

Updated August 18

Every spring, humpback whale mothers bring their calves northward from their winter breeding and calving grounds in the Dominican Republic to feed in the productive Gulf of Maine waters. One of the most popular places for humpback moms to bring their calves is the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of Massachusetts. In our survey area, although close by, we generally see fewer calves.

On average, we have two sightings of mother-calf humpbacks each year, but so far this year we have had six sightings of mother-calf pairs, the highest annual total in ten years of surveys! Five of these pairs were observed in the bubble-feeding aggregations that persisted throughout the summer (mentioned below), which highlights how productive this area can be for foraging.

While they are still too young to bubble-feed on their own, some calves we’ve seen this summer have been observed attentively waiting at the surface while their mother was bubble-feeding. These calves were perhaps watching to learn this feeding technique for when they are weaned and have to feed on their own. Other calves were very active at the surface and were breaching, flipper slapping, and rolling! While spring and summer are our most common seasons to see calves, we are hopeful to see another pair this fall!

All in the family: Humpback siblings spotted in the same feeding area

Updated August 8

All large whale species have certain physical characteristics that allow us to identify them individually. Right whales have unique callosity patterns on the top of their heads, which makes them perfect subjects for identifying from a survey plane. Humpback whales are mostly identified by the pattern on the underside of their fluke, or tail, which means that most of the humpbacks we see on our surveys, we can’t identify as an individual. However, sometimes we get lucky if a whale rolls over while feeding or socializing.

When we are able to photograph the underside of the fluke on our aerial surveys, we send photos to the Humpback Whale Studies Program at the Center for Coastal Studies to identify the individuals based on their unique features. In late June we photographed a bubble-feeding aggregation that had two well-known Gulf of Maine humpbacks that are actually sisters: Thalassa and Mostaza!

These whales are the daughters of Salt, one of the most famous humpbacks and among the first humpbacks to be recognized by researchers in Cape Cod Bay in the 1970s, due to the white scarring along her dorsal fin that looks like salt was sprinkled on it. Thalassa (born in 1985) and Mostaza (born in 2000) are both adult females who have each had several calves.

On our survey, Thalassa was flipper-slapping at the surface, which allowed us to get some good photos of the underside of her fluke. Mostaza was bubble-feeding and would often roll upside down when she surfaced–giving her own unique “spin” on the feeding technique. We had previously documented Mostaza feeding in May, so it was great to see her still in the area! While it is tempting to think that Thalassa and Mostaza stick close to each other because of their family ties, we know that humpbacks don’t exhibit long-term associations with family members. It’s more likely that they were both drawn to the area by the large schools of prey fish! We are grateful for the opportunity to collaborate with the Center for Coastal Studies and contribute sightings to their humpback whale catalog.

Bubble-feeding!

Updated July 20

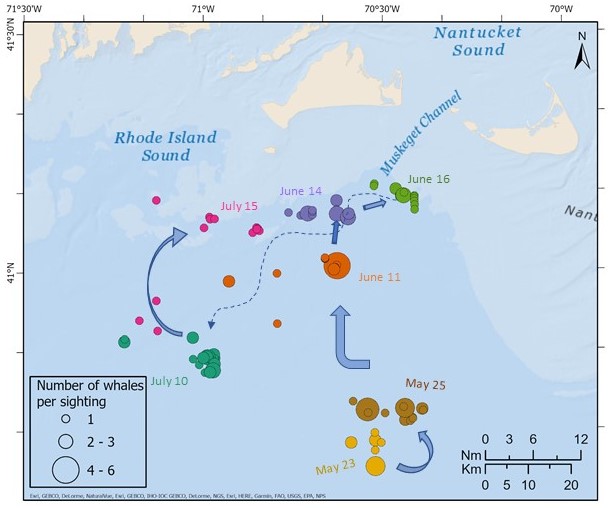

In New England, especially during the summertime, humpback whales are well-known for bubble-feeding — a technique in which they exhale a circular net of bubbles to corral their prey (small fish) inside. This allows the humpbacks to then swim up to the surface with their mouths open through the bubble net and consume the concentrated prey caught within the circle of bubbles. Over the last few years, we have seen bubble-feeding in our survey area mostly during late spring and summer.

This year, we first documented an aggregation of humpbacks bubble feeding in late May that was 46 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard near the New York shipping lanes. This aggregation continuously shifted northwards in June and also grew in size to over 20 individuals including several mother and calf pairs! Bubble-feeding continued during our July surveys, and we were constantly left guessing where the whales would be as they shifted location. Stay tuned for more aerial survey updates!