Join the BalanceBlue Lab for a Seaweed Safari

Follow the team from the BalanceBlue Lab at the Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life around the globe and learn about responsible seaweed farming and harvesting.

By New England Aquarium on Wednesday, December 18, 2024

What do ice cream, toothpaste, and sushi all have in common?

If you guessed seaweed, then you’re right!

Besides being a yummy snack, seaweed can also be an important source of extracts, such as alginates and carrageenan. These extracts, which act as thickening or stabilizing agents, can often be found as ingredients in many common foods and household products and even have important medical applications. Seaweed is also incredibly important to the marine environment, particularly as a food source and shelter for many different species. For example, one study in Norway found that on average, almost 8,000 individual organisms live on a single kelp. That makes seaweed beds kind of like underwater cities!

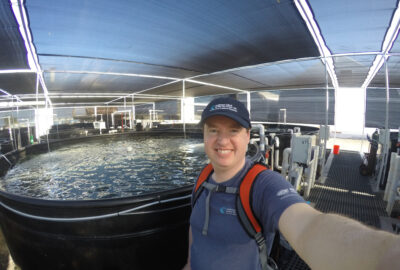

Because seaweed is so important to the ocean and people, the BalanceBlue Lab at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life is working to increase the adoption of environmentally responsible seaweed harvesting and farming practices. BalanceBlue Lab is a science and innovation hub that utilizes cutting-edge research and market-based solutions to support responsible ocean use and promote a blue economy that protects our ocean. We drive entrepreneurs, ocean industries, and others toward ocean-friendly practices, sustainability goals, and climate adaptation strategies.

This year, we traveled all over the world to get up close and personal with many species of seaweed and to learn more about different harvesting and farming practices.

Come join us for part one of our seaweed safari!

May: Massachusetts, USA – Irish moss (Chondrus crispus)

Our seaweed safari started in the New England Aquarium’s very own backyard in Scituate, Massachusetts! Back in May, the BalanceBlue Lab team visited the Scituate Maritime Irish Mossing Museum, where we learned that the region used to be an important hub for seaweed harvesting. Commercial collection of Irish moss (Chondrus crispus) seaweed for use as a thickener and gelling agent on the South Shore began around the mid-1800s and continued well into the late 1900s. Irish moss was harvested at low tide using a long rake, which cut the tops off the seaweed without ripping away the part of the seaweed that attaches to rock, which is called a holdfast.

Leaving the holdfast attached allows this species of seaweed to grow back after harvesting, similar to how grass grows back after you mow a lawn, and therefore is an important consideration for industry and resource managers alike. At the museum, we also saw some of the wooden boats used by seaweed harvesters (who were called “mossers”) to transport seaweed back to the beach, where it was rinsed and dried. It was so awesome to start our seaweed journey right at home by learning about a little-known part of Massachusetts history!

June: Iceland – Rockweed (Ascophyllum nodosum)

In June, BalanceBlue Lab members Emiley and Lena journeyed to the remote coastlines of Iceland, where there are more birds than people! This region harvests a species of seaweed called rockweed (Ascophyllum nodosum), which you may also notice growing on shores in places like Maine and Atlantic Canada. The seaweed harvesting method we observed uses specialized small boats, which act sort of like lawnmowers, cutting the seaweed just above the holdfast. Like Chondrus crispus, Ascophyllum needs to be harvested above the holdfast to ensure that the resource regrows before it is harvested again. Other practices to reduce the environmental impact of seaweed harvesting are also used, such as only harvesting an area once every three to five years and avoiding harvesting during important times of year for other species, such as during eider duck (Somateria mollissima) nesting season.

During our visit, we observed seaweed harvesting operations, including looking for signs of bycatch (non-target species that might be accidentally taken along with the seaweed), and watched how other wildlife, such as seabirds, responded to seaweed harvesting operations. These types of observations help us understand how harvesting Ascophyllum might impact the local ecosystem. Happily, seaweed harvesters in this area are very committed to keeping their environmental impact to a minimum.

In our downtime, we also were able to spend a little time exploring the region, including visiting local hot springs, hiking to the Guðrúnarlaug waterfall, and making a trip to the very spooky Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft! We also had ample opportunity to practice our birdwatching skills – junior ornithologists Emiley and Lena identified thirty-four species of birds in three days!

August: Tasmania, Australia – Bull kelp (Durvillaea potatorum)

Next, the BalanceBlue Lab was off to Australia! After a very long flight, Matt and Lena ventured to a small island in the Bass Strait, where people have been collecting beach-cast seaweed— seaweed that has been washed up onto shore from waves and wind —in pretty much the same way for over sixty years! The seaweed harvested in this area is called bull kelp (Durvillaea potatorum), which thrives in rocky, high wave-energy environments and can grow to be over twenty feet long! Because bull kelp is so large and can be quite heavy, seaweed harvesters will tie a rope around individual stipes (the seaweed “stem”) and winch the seaweed onto pickup trucks. Harvesters hang the collected kelp from handmade wooden racks to dry before it is processed. Dry bull kelp is thick and feels almost like leather!

Since beach-cast bull kelp collection does not remove attached seaweed from the marine environment, it does not have the same environmental considerations as other types of wild seaweed harvesting. However, harvesters can still take steps to reduce environmental impacts, such as by keeping their trucks in established tire tracks to avoid disturbing the beach ecosystem and by leaving some seaweed on the beach to maintain sources of food and shelter for species of shorebirds and other local wildlife.

Speaking of local wildlife—we saw plenty on our trip, including a napping fur seal (Arctocephalus pusillus), lots and lots of Bennet’s wallabies (Macropus rufogriseus), a white-bellied sea eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster), and even nesting fairy penguins (Eudyptula minor)! We also got to meet a local scientist who is hoping to understand how the distribution of bull kelp – a cold-water species— on beaches on the island might be changing as a result of climate change.

We hope you will join us again soon for part two of our “seaweed-ventures!”

Much of the work described above was made possible through a partnership collaboration with IFF’s Responsible Seaweed Sourcing Program. The BalanceBlue Lab would also like to extend our thanks to the many wonderful seaweed experts who hosted us during our travels and shared their knowledge with us.

For more information on IFF’s Responsible Seaweed Sourcing Program, you can visit: The Science and Creativity of Sustainable Seaweed