From Gaps to Discoveries: The Raja Ampat Epaulette Shark Research

By New England Aquarium on Friday, August 16, 2024

This post is one of a series on projects supported by the New England Aquarium’s Marine Conservation Action Fund (MCAF). Through MCAF, the Aquarium supports researchers, conservationists, and grassroots organizations around the world as they work to address the most challenging problems facing the ocean.

By Maula Nadia and Faqih Akbar Alghozali – Elasmobranch Project Indonesia

The Importance of Kalabia

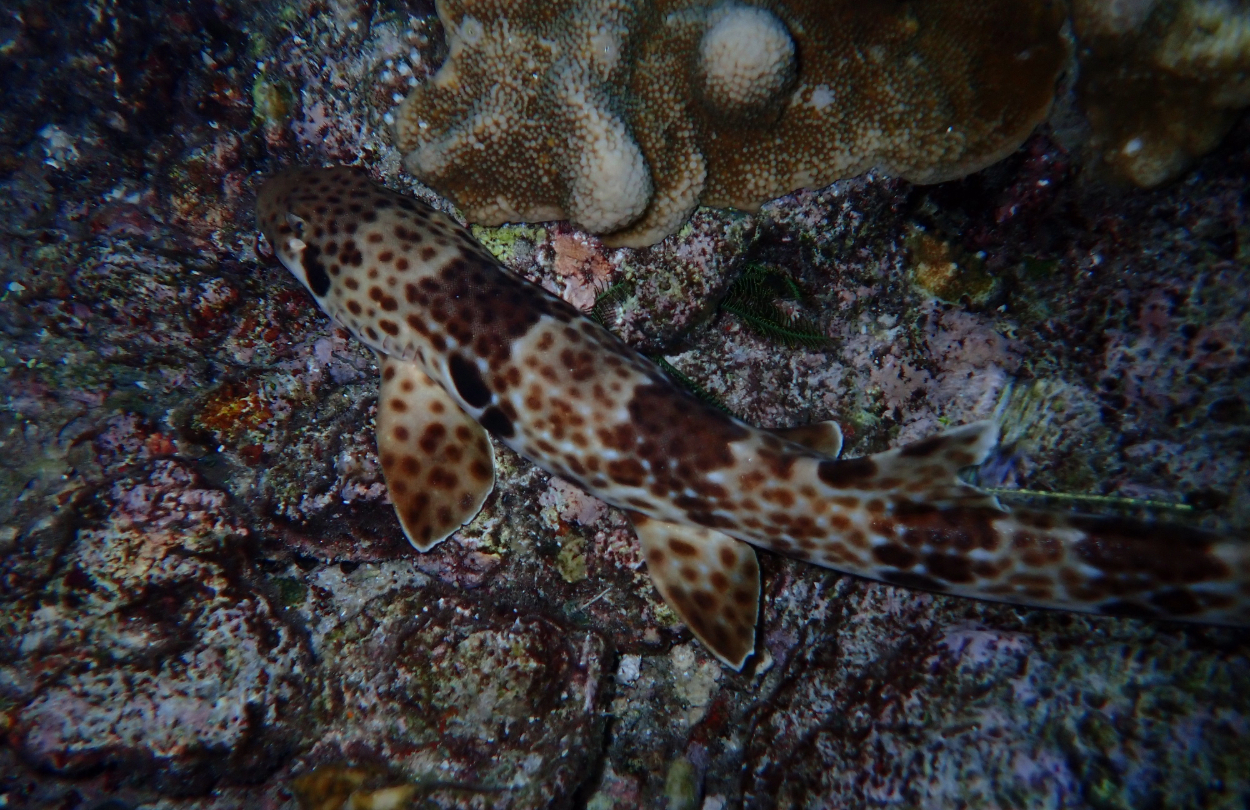

The Raja Ampat epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium freycineti)—known to locals as kalabia or mandemor—is a unique and precious species for the Raja Ampat Islands, our team, and shark and ray conservation in Indonesia. The kalabia was the first species that our team, the Elasmobranch Project Indonesia (EPI), worked with in the field. This native species only existing in the Raja Ampat region further fuelled our team’s fascination, in addition to it being the most reported species submitted by divers on our citizen science platform. The uniqueness of this species is that this shark can ‘walk’ with its fins, a shared trait with the other eight epaulette shark species across Maluku, Papua, Papua New Guinea, and Australia. Unsurprisingly, as the eastern part of Indonesia is a biodiversity hotspot, the Kalabia has five sister species distributed across the region—still, much about this species remains a mystery to scientists.

The EPI realized that the kalabia still had puzzle pieces of information that needed to be uncovered to complete our knowledge of this species in Raja Ampat. Based on discussions our team had with the Konservasi Indonesia team and some of the previous assessors of the species’ International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List conservation status, we believe there is still a lot to learn about the kalabia. Many questions such as their actual threats, how they were distributed across islands in Raja Ampat, and what species may predate on them, are only a few among the many enigmas surrounding the species. This situation is an alert for Indonesia to put more effort towards conserving this majestic endemic species to prevent their extinction. Noticing this, our team initiated the Kalabia Project, where we went to the field to directly contribute towards the research and community engagement for kalabia conservation in Raja Ampat.

It was a boost for our team and Indonesia that all epaulette species, including the kalabia in Raja Ampat, were fully protected in early 2023 under the Ministerial Decree of the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries No. 23/2023. Considering Raja Ampat as a tourism hotspot globally and its vast range of marine protected area networks, the kalabia has considerably high protection across its distribution range. However, even if this protection creates less human threats to the species, other dangers might still pose a threat to kalabia if we neglect the present knowledge gaps. We believe that our Kalabia Project will support the implementation of the newly established full protection of epaulette shark species regulation.

Answering Key Questions

After conversing with the local community in Yenbuba and Arborek, our team believes there are no man-made threats present for kalabia across the areas of each village, even the Dampier Strait. However, the locals and our team did find multiple instances of plastic waste and fishing gear remains (ghost gear), which are a potential external threat to the local kalabia population. Although we have a better understanding about the kalabia in these two villages, the locals stated that they did not know whether it is the same for other areas in Raja Ampat.

Surprisingly, the locals did not know much about the kalabia aside from the fact that they come to the shore as the locals are cleaning fishes for dinner or for guests in the homestays. Most of the community did not know how to differentiate between male and female sharks, what they eat, and how they reproduce. The locals did not even know the species was already fully protected six months after the regulation was established.

Although our team only stayed for around three months in Raja Ampat, we managed to learn a lot about kalabia biological and ecological information. It turned out that the kalabia are five to 10 times more abundant than was stated in the IUCN Red assessment of the species, at least in Yenbuba and Arborek. The team also learned that their presence was not reliant on the presence of coral reefs, where we assume that they could be found as long as there are substrates that can serve as shelter (coral, mangrove trees, rock, rubble) and foraging areas for food that is relatively close to their shelters. We also discovered that their presence was affected by temperature and was more abundant during low tides. These results led to the assumption that kalabia might share the same behavior in terms of feeding as another epaulette species, Hemiscyllium ocellatum, and that they use substrate and tides to strategically avoid predators like the blacktip reef shark (Carcharhinus melanopterus) and the moray eel (Muraenidae). Their strong connection with the coastal ecosystem made us believe they are highly influenced by the health of the ecosystem. Increasing environmental variability due to climate change, together with environmental degradation, are driving changes in their habitat, which may lead to concurring effects to the species in the long term.

Community Support

Our Kalabia Project was kindly welcomed by the locals and the authorities, locally and nationally. The community showed great enthusiasm as we presented our initial findings with them, where they asked many questions that our team was not yet able to answer and they showed their eagerness to further spread the word of kalabia conservation to others in Dampier Strait, if not Raja Ampat. The local authority, Badan Layanan Umum Daerah Unit Pelaksana Teknis Daerah (BLUD UPTD) Pengelolaan Kawasan Konservasi (KK) di Perairan Kepulauan Raja Ampat, was grateful for the project as it will help to leverage future conservation works of the kalabia in Raja Ampat. The project has also conveyed that the photo identification used in the research was confirmed to be a viable approach to monitor the kalabia population, where it could be integrated with the monitoring guideline and citizen science platform for kalabia that our team, KI, and BLUD UPTD KK Raja Ampat is currently developing together.

The success of our project in filling many knowledge gaps and research questions came down to the fact that our team was well-prepared in terms of skills, equipment, network, collaboration, and communication. The project was supported by KI and BLUD UPTD KK Raja Ampat both behind the scenes and in the field. Locals were very supportive and eager to learn during the kalabia population monitoring. Even if sometimes the weather conditions were not favorable or there were situations where our team needed to make some adjustments, we believe that we managed to overcome these challenges due to the nature of our well-preparedness for the project. Most importantly, our team feels that we have laid a strong and robust foundation for future research and conservation efforts for kalabia in Raja Ampat, and hopefully will motivate others to contribute to and continue the legacy for kalabia or other epaulette species in Indonesia, together with EPI, KI, and the BLUD UPTD KK Raja Ampat. We also hope our ongoing journey for the kalabia can inspire more efforts for other species that are often overlooked in order to protect the populations and biodiversity of sharks and rays in Indonesia.