The Aquarium will be closed to the public on Wednesday, April 2, for an internal staff event. Regular operating hours will resume on April 3.

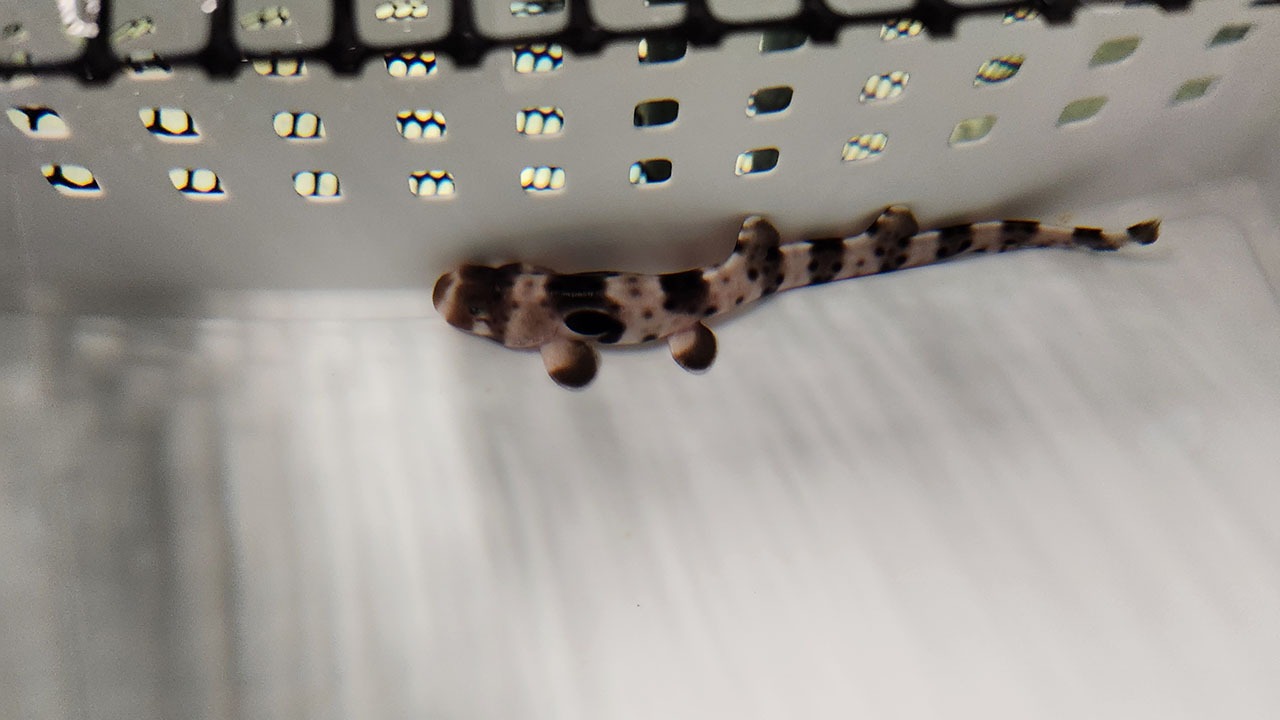

Welcoming Epaulette Shark Hatchling #100

We caught up with Sarah Tempesta, one of our Animal Care experts, to learn more about this milestone in our epaulette shark-rearing program.

By New England Aquarium on Thursday, February 15, 2024

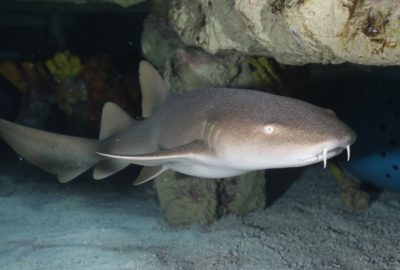

Since the mid-2000s, the New England Aquarium has been rearing epaulette sharks—the spotted sharks found in the waters around the Great Barrier Reef—for display, research, and sharing with other institutions. In the program’s early stages, the team experimented with different processes before landing on a successful method—and a new numbering system for the hatchlings, which began in 2012.

“Having an in-house numbering system allows us to identify and track each shark throughout its lifetime, and with our record-keeping database allows us to access each individual animal’s history and provide the highest standard of care,” said Sarah Tempesta, manager of Interactive Exhibits and an experienced aquarist who helps lead our shark-rearing program.

Just this past January, the team welcomed epaulette shark #100 in that numbering system. The male hatchling is siblings with nearly all of our current epaulette sharks—most of whom are females, in order to keep a healthy genetic population here at the Aquarium. The sire, or father, of our epaulette sharks, at 22 years old, is one of the oldest animals on record in the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) studbook program, which documents the pedigree and entire demographic history of animals in the care of AZA-affiliated institutions. He was acquired by the Aquarium in 2008.

While epaulette shark #100 lives behind the scenes, he’ll soon be big enough to join other juvenile epaulettes in our Science of Sharks exhibit, where he’ll stay for up to a year and a half. After that, our team will transfer him to another institution. “We never keep males here because all of his tankmates in the larger Shark and Ray Touch Tank are his relatives,” said Sarah, “so we’ll work to rehome him to another institution.”

Epaulette sharks are considered a species of least concern on the ICUN red list, which means they aren’t currently threatened in the wild. Still, rearing them at the Aquarium benefits our institution and others, providing a sustainable population of epaulette sharks to display in exhibits. “Whenever we have surplus sharks, we’re able to send those to other aquariums that want them,” Sarah said. Over the years, at least 67 epaulette sharks born at the Aquarium have gone on to live at other institutions.

The team at our Quincy Animal Care Center has also collaborated with our Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life scientists to research the effects of climate change on epaulette shark development. In 2021, Caroline Wheeler, a PhD candidate at the University of Massachusetts Boston, worked with members of our Animal Care team, who reared eggs for her research into how increasing temperature impacts the growth and development of shark embryos. Her research showed that, in warmer conditions, the baby epaulette sharks were born smaller and less able to thrive—signaling that rising ocean temperatures could have significant negative effects on wild shark populations.

It takes five months for a baby epaulette shark to hatch after the egg is deposited by a female, and about seven years for the shark to be fully grown. In our shark-rearing program, our females deposit eggs year-round. Because their conditions in our care are much more stable than in the wild, they don’t follow a “breeding season” and lay eggs about once a month.

Around ten days after an egg is laid, the team determines if it’s viable, which they do through a process called “candling,” or illuminating the egg sac so any embryo is visible. If Sarah and the team decide to rear the shark until it hatches, they’ll continue to candle the egg throughout its development to monitor the baby shark’s progress. Through this process, between three to five epaulette sharks are born at the Aquarium each year.

So, after 100 epaulette hatchlings, does Sarah have any memorable sharks to look back on?

“Epaulette #49 stands out to me,” Sarah said. After developing a jaw malalignment, #49 initially struggled to eat appropriately and couldn’t compete with her tankmates for food. “I trained her to come up to the surface into a basket to feed so she wouldn’t have to compete,” Sarah said, “we did this for many years until she could feed independently outside her basket.” With the care she received from Sarah behind the scenes, epaulette #49 is now thriving with her fellow sharks in our Science of Sharks exhibit.

“This is a really exciting milestone and shows the experience and success we’ve gained with this species,” said Sarah, of the successful hatch of epaulette #100. “Caring for animals throughout their entire lifespan allows us to learn more about their development, characteristics, and longevity, which ultimately allows us provide them the ability to experience excellent welfare.”