Battery Powered Research

Using electronic tags and computer models to understand capture-related mortality and predation of yellowfin tuna released in a recreational troll fishery

By Jeff Kneebone, PhD on Tuesday, March 23, 2021

“Catch and release” – the act of releasing a fish either voluntarily or in compliance with a fishing regulation – is frequently practiced as a species conservation or management tool. However, depending on the species and fishery, fish sometimes die after being thrown back as a result of the physical or physiological impacts of being caught, handled, and released. If a large percentage of released fish die, then catch and release is no longer a viable conservation tool to preserve fish populations. It is therefore critical to know why death occurs and how many fish experience capture-related mortality in order to design best-practice capture and handling recommendations or fishing regulations aimed at minimizing negative impacts of catch and release. In the past couple years scientists at the Fisheries Science and Emerging Technologies group at the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life have enlisted the help of electronic devices such as pop-up satellite archival tags and laptop computers to study the impacts of catch and release on several popular recreational species and promote the use of responsible catch and release practices by the recreational fishing community.

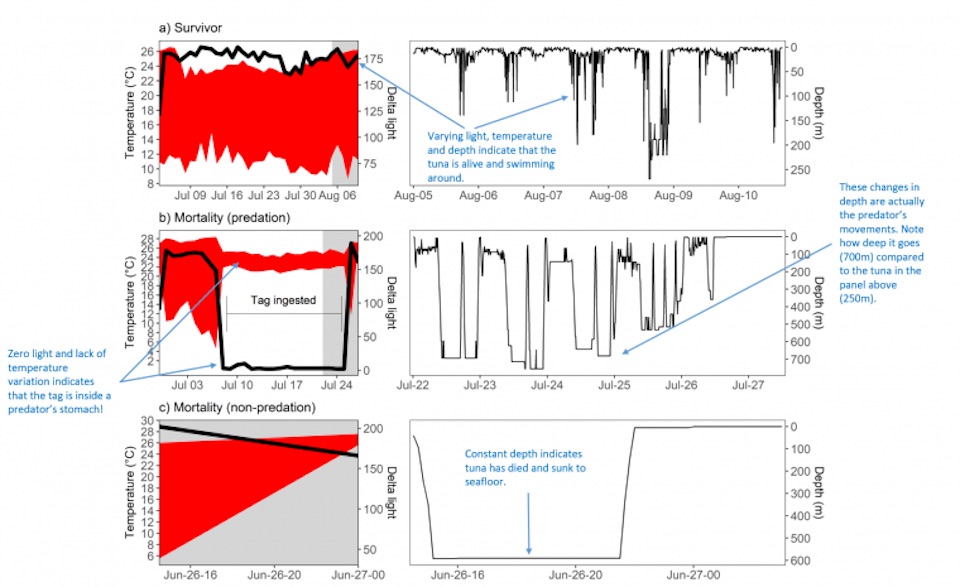

Pop-up satellite archival tags (or PSATs) are amazing little devices that collect detailed data on light intensity, temperature and depth of the water that an animal is swimming through over the course of several weeks or even months. Although we often use these data to study fish movements and migration, the high resolution data collected by PSATs also gives us the ability to document the behaviors and fate of released fishes in the days to weeks following release. These battery-powered tags can even identify instances when predators consume a tagged fish after it’s released! Despite this incredible feat, it is sometimes difficult to determine whether observed mortality events, including predations, occur due to impairment from the capture and handling process (that is, are a form of capture-related mortality) or occur due to natural causes. Therefore, rigorous review and analysis of electronic tag data is needed to properly account for and estimate different sources of mortality.

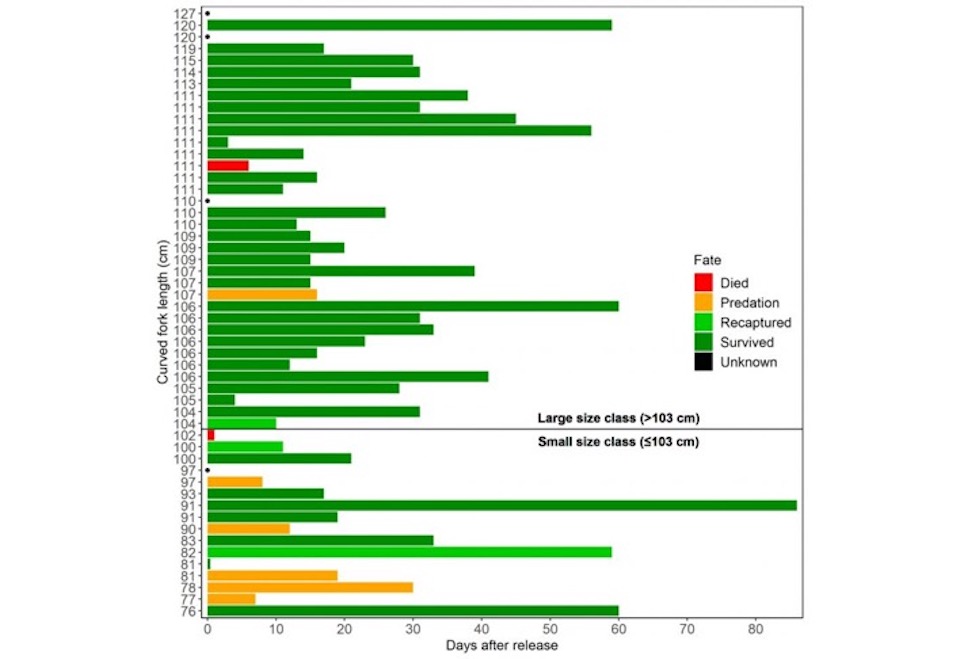

Recently, our research team used PSATs to monitor the fate of 48 yellowfin tuna following catch and release in the popular recreational troll fishery off the U.S. east coast and found that 8 tuna died within 30 days after release. Remarkably, 6 of those 8 tuna died as a result of being eaten by a predator–possibly a shark, marlin, or swordfish–from 7 to 30 days after being released. Using a sophisticated mathematical model, the team showed that these predations likely occurred as a result of lingering impacts from catch and release and therefore were a form of capture-related mortality. The model also revealed that capture-related mortality rates are over 6 times higher in yellowfin that are smaller than 103 cm (51%) than in larger individuals (8%).

Since smaller yellowfin tuna are frequently released in the recreational troll fishery, our findings indicate that capture-related mortality of yellowfin tuna in this popular fishery may be quite high. Thus, to reduce capture-related mortality–and the chance that released tuna are eaten by predators–recreational fishermen should consider avoiding schools of small yellowfin tuna, retaining smaller (but still legal-sized) yellowfin tuna instead of larger individuals, and potentially using large lures to select for larger fish. Fishermen should also follow the capture and handling practices recommended by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Highly Migratory Species Management Division by releasing tuna without removing them from the water as required in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico under U.S. law.

You can read more about this research in two recently-published scientific papers available at the following links:

This research was supported by NOAA’s Saltonstall-Kennedy Grant Program.

Research team and study participants:

- Dr. Jeff Kneebone (Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life)

- Dr. Hugues Benoît (Department of Fishes and Oceans Canada)

- Dr. Diego Bernal (University of Massachusetts Dartmouth)

- Dr. Walt Golet (University of Maine)